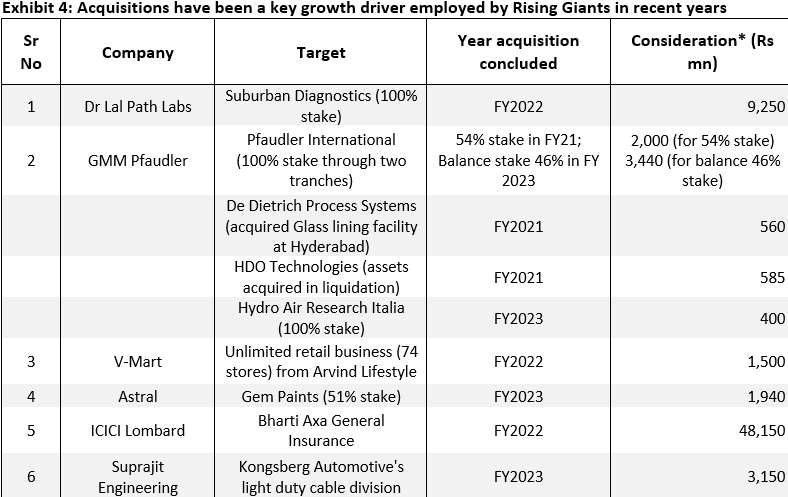

Acquisitions have been a cornerstone of Rising Giants’ growth strategy in recent years facilitated by burgeoning internal accruals and the consolidation opportunities thrown up by Covid-19. In contrast to the abysmal track record of Indian corporates generally with respect to acquisitions (particularly, international ones), the Rising Giants’ measured approach in terms of acquisition size, their aversion to deep turnaround bets, their investments in related businesses and their scaling up of management bandwidth gives us confidence regarding their inorganic growth strategies.

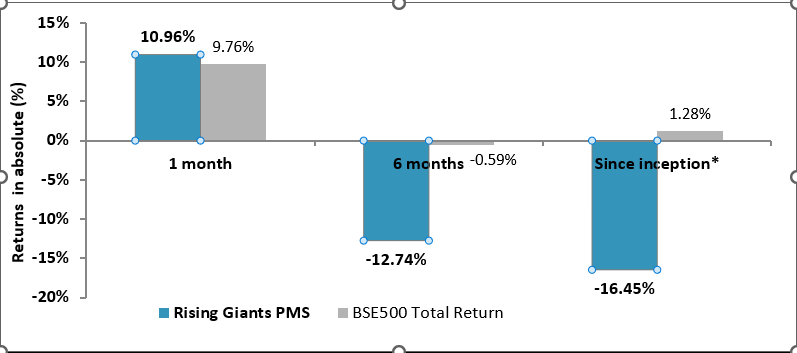

Performance update for the Rising Giants PMS

This portfolio intends to invest primarily in high quality mid-sized companies (less than Rs 75,000 crores market-capitalisation, predominantly in the Rs 7,000 crores – 75,000 crores range) with: 1) Well moated dominant franchises in niche segments; 2) A track record of prudent capital allocation with high reinvestment in the core business and continuous focus on adjacencies for growth; and 3) Clean accounts and corporate governance. From a universe of ~450 companies in this segment, a portfolio is constructed of 15-20 companies which make it past Marcellus’ proprietary forensic accounting & capital allocation filters as well as our bottom-up stock selection & position sizing frameworks.

Exhibit 1: Rising Giants PMS performance vs the benchmark BSE 500

Source: Marcellus Investment Managers. Note: (i) *Portfolio inception date is December 27, 2021. (ii) Returns as of July 31, 2022. (iii) Performance data is net of annual performance fees charged for clients whose account anniversary falls upto the last date of the performance period. Since fixed fees and expenses are charged on a quarterly basis, effect of the same has been incorporated up to 30th June, 2022. (iv) Returns shown above are net of transaction costs and includes dividend income. (v) Total returns index considered for BSE500 above.

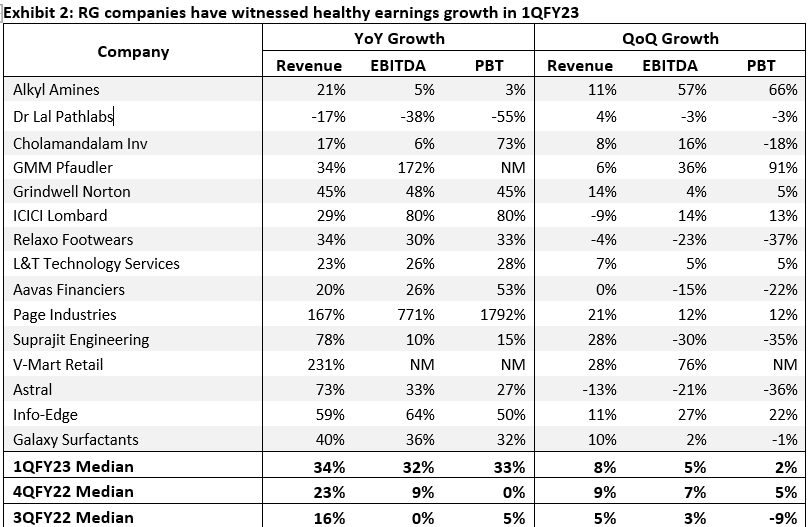

Rising Giants witnessed healthy earnings growth in 1QFY23

In 1QFY23, the Rising Giants companies continued their path of rapid earnings compounding. On a median basis, in 1QFY23 the YoY Revenue and PBT growth were 34% and 33% respectively for the portfolio. This YoY growth in revenue and profitability is much higher than that witnessed in the previous two quarters viz. 3QFY22 and 4QFY22 which were impacted, as discussed in our previous months Rising Giants newsletter, from supply chain disruptions and input price inflation.

Source: Companies, Ace Equity, Marcellus Investment Managers; Notes (i) For financial services stocks namely – Aavas Financiers, and Cholamandalam Inv, PPOP is EBITDA and revenue is total net income (NII + other income) and for ICICI Lomb, Net Written Premium is revenue. (ii) NM: Not measurable since negative number either in the current or base quarter;

While the YoY trend in 1QFY23 benefited from the weak base of 1QFY22 (which was impacted by the Covid-19 second wave), the portfolio median PBT CAGR works out to 17%3-year CAGR basis (i.e. on a pre-Covid 1QFY20 base) reflecting the underlying compounding muscle of these franchises.

Evaluating the inorganic growth strategy of Rising Giants

Rising Giants have hit the ‘inorganic growth’ button in recent years

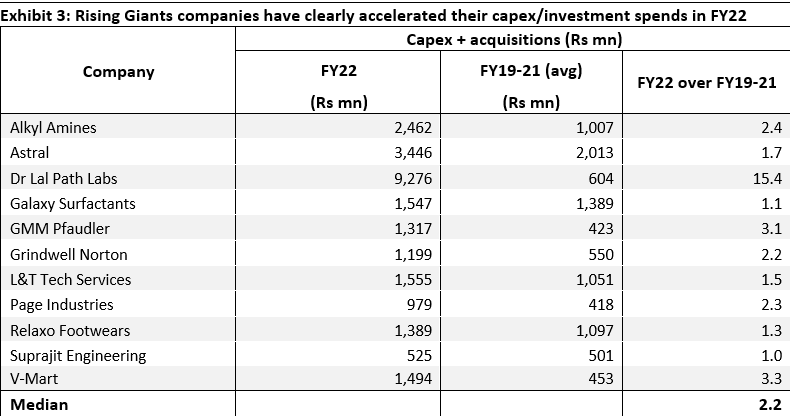

One of the defining success factors for the Rising Giants vs their peers have been their high capital reinvestment initiatives to either strengthen the existing business (and thus gain market share) and/or add new growth drivers. A detailed explanation on Rising Giants’ reinvestment strategy and the result of the same in the form of growth, improved profitability and better cash generation can be found in our Rising Giants April 2022 newsletter.

In recent quarters, the Rising Giants have further accelerated their reinvestment levels thus capitalising on the war chest built through strong internal accruals and exploiting the market opportunities for consolidation (domestic as well as global) brought upon by Covid-19. At the portfolio median level, the capex/strategic investments undertaken by Rising Giants companies in FY22 is more than 2x the corresponding annual average between the FY19-21 period.

Source: Companies, Ace Equity, Marcellus Investment Managers. Note: (1) The above does not include financial services stocks in the portfolio namely – Aavas Financiers, Cholamandalam Investment, ICICI Lombard General Insurance and Info-Edge since Capex is not a relevant metric for such companies

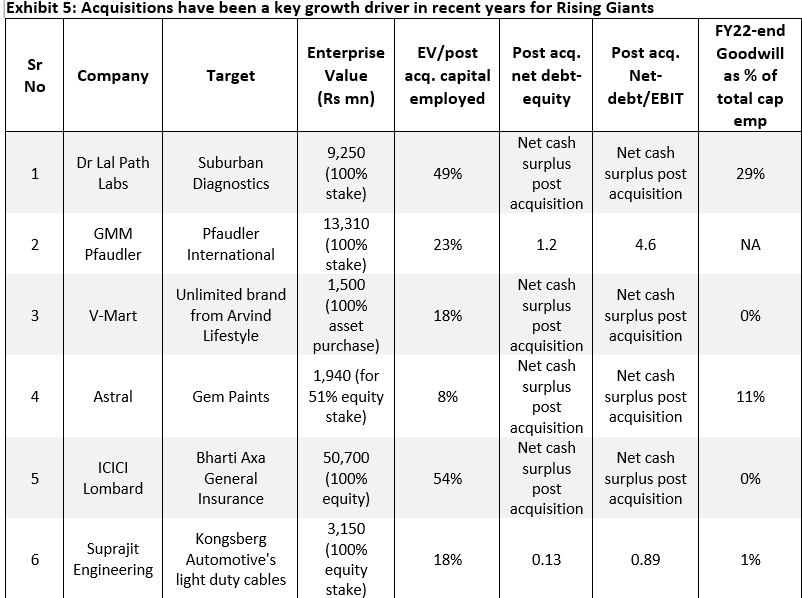

A significant portion of the above reinvestments in the recent years has gone towards acquiring companies in India as well as globally. The below exhibit highlights the key acquisitions undertaken by Rising Giants companies in the last 2-3 years.

Source: Marcellus Investment Managers, Companies. Note: (1) The consideration mentioned above is only the equity consideration paid rather than the full enterprise value of the transaction and is shown proportionate to the stake acquired.

Indian companies have a woeful track record when it comes to global acquisitions

Globally, companies spend anywhere between $3-4 trillion annually on M&A activities (as per data available since 2014). However, studies suggest that the failure rate of mergers and acquisitions is between 70-90%[1]. The figures are not very different from an Indian standpoint with studies conducted by consultancy firm KPMG finding that 75% of the acquisitions made by local firms have failed to create substantial value from the deals and 59% of the acquirers have actually destroyed value within a year of closing a deal[2]. Historically, even though there have been cases of successful integration of acquired Indian businesses, international acquisitions by Indian firms have mostly left behind a tale of value destruction. (Source: Newsarticle 1, Newsarticle 2)

As we had written in our Feb’20 Consistent Compounders newsletter: “Between 1995 and 2005, there have been various examples of firms deploying their surplus capital towards M&A to acquire businesses in India. Many of these ended up generating substantial value for shareholders with ROCEs of the acquired businesses being well above their cost of capital. Some examples of these successful acquisitions include: Hindustan Unilever’s acquisitions of TOMCO (Tata Oil Mills Company), Kwality, Brooke Bond, Kissan, Lakme, etc during the 1990s; Dabur’s acquisition of Balsara (2005); Marico’s acquisition of Nihar (2006); and Pidilite’s acquisitions of Ranipal (1999), M-Seal (2000), Dr. Fixit (2000), Steelgrip (2002), Roff (2005), etc. These acquisitions have successfully added sustainable earnings growth drivers for these firms with high ROCEs.

However, after 2005, several dominant Indian companies have deployed surplus capital towards international expansion / acquisitions – for example GCPL (Africa, Indonesia, Latin America), Pidilite (Brazil, US, Middle East), Marico (Middle East, Bangladesh, South Africa), Dabur (Africa, US, Turkey, Egypt), Havells (Sylvania), Tata Steel (Corus), Asian Paints (Berger International, 2001), Bharti Airtel (Africa), etc. Most of these acquisitions have delivered ROCEs well below cost of equity.”

Some of the most common factors behind the abysmal success rate of acquisitions by Indian firms are:

Size of acquisition & financial leverage: Paying an outsized amount (in relation to one’s balance sheet) for an acquisition and then financing the same using debt is a recipe for disaster. In such a strategy, a wrong bet has the potential to severely damage the acquirer’s balance sheet. Many of the biggest M&A blunders by Indian companies have been characterised by this strategy.

Tata Steel – Corus[3]:Corus acquisition was an aspirational mistake”- JJ Irani, former MD at Tata Steel, April, 2017, Economic Times.

In 2007, Tata Steel acquired Corus for GBP6.2 billion ($12.1 billion) in one of the largest cross-border acquisitions in Indian corporate history. Half of this amount -$6billion was paid for by using debt (PAT for the company was $1 billion in FY2006-07). As the commodity cycle peaked later that year followed by the global financial crisis, steel businesses globally got hammered. Later, the Eurozone crisis combined with cheap Chinese steel flooding the market meant that the pricey acquisition could never live up to its promise and remained an overhang for the group entity for more than a decade. While one can say that no one really could’ve predicted the way things panned out, a few warning signs were clear. For example, a decision to pay 34% higher price than the original offer after getting into a bidding war with Brazilian rival CSN was not well received by investors who pummelled Tata Steel’s stock 11% on the day after it won the bid. Financing the all-cash deal using debt was also a red flag. The investment was also made in a climate when there was a tremendous buzz about outward foreign direct investment (FDI), and many Indian industrialists were the subject of world’s adulation for making global enterprises. While great from promoter/managements’ image building perspective, such times are hardly great for acquisitions from shareholder perspective. (Source: Newsarticle 1)

Complexity, inability to bridge differences in organisational culture and stretched promoter/management bandwidth: It is operationally difficult for an Indian company to manage an acquired business which operates in an unknown (or lesser known) geography. Many firms tend to underestimate the importance of alignment of the softer aspects of business for success in managing the overall merged entity. Similarly, in firms which have historically been centrally controlled by a dominant promoter, acquisitions mean that the promoter’s time and bandwidth constraints result in the professional managers having less-than-ideal amounts of clarity on tasks & roles. This in turn leads to sub-optimal decision making for both non-core and core businesses.

Airtel -Zain[4]: In 2010, Bharti Airtel acquired Zain Africa for an enterprise value of US$10.7 billion and the deal was funded using debt financing of almost $8.5 billion. Expansion into Africa was a way to increase the geographical presence for the firm and to compete with larger, global telcos such as UK-based Vodafone Group Plc. and Norway-based Telenor ASA. It also needed a fresh growth driver with the Indian market reeling from tariff wars and expensive spectrum acquisitions. Low penetration and high ARPU (>$3/month) vs. India (<$1.5/month) made the acquisition a logical step. However, Zain was bleeding cash and Airtel ploughed in $5billion cash over next 5 years reorganizing the networks and sales and distribution infrastructure in the continent, among other things- showcasing the risks of buying an asset on turnaround hopes. Airtel also rushed into the deal without adequate understanding of local African market and the challenges of cultural integration. Further, the management bandwidth was also squeezed shuttling between India, the core market and Africa as the company underestimated the complexity associated with 15 different African markets with their own regulations and demographics. (Source: Newsarticle 1, Newsarticle 2)

Acquisition of unrelated businesses: This aspect is many a times an outcome of management hubris borne out of success in their core business which seeds the belief that success is assured irrespective of which path they take. In a quest towards ‘empire building’ such a company redirects valuable resources towards non-core businesses with no competitive advantages, potentially harming their existing business also in the process. Common examples of this in the Indian corporate landscape have been the great rush between 2006 to 2011 by many Indian corporate groups to invest in telecom licenses, infrastructure assets and power generation. Such forays eventually led to the downfall of many such groups

What makes us confident about the Rising Giants’ inorganic foray?

As discussed above, the track record of Indian firms with regard to inorganic expansion has not exactly been covered in glory. In this context, should we worry about the inorganic forays of Rising Giants? We remain sanguine about our portfolio companies’ inorganic strategy due to the following reasons:

Modest amounts of capital allocated towards acquisitions: Given one of the most common reasons for an acquisition to go awry is the use of excessive leverage to buyout a target company, we look at how RG companies have done with respect to this measure. As shown in the table below, most of the recent acquisitions have been of modest size vis-à-vis the size of acquirer’s balance sheet with the acquisitions mostly funded through internal accruals or shares swap. For most of the portfolio companies below, even after acquisitions, the balance sheet continues to have net surplus cash (even after taking the entire debt burden into account).

In some of the portfolio companies like Dr Lal, ICICI Lombard and GMM Pfaudler, the size of the acquisitions looks high when one looks at % of the capital employed towards acquisition. However, Dr. Lal and ICICI Lombard are asset light companies. For both these companies, even post acquisition, there is a cash surplus sitting on the balance sheet. Another measure of looking at reasonability of capital paid for acquisition is amount of goodwill generated as % of networth or capital employed – here too barring Dr Lal Pathlabs, goodwill is insignificant for other companies. In case of Dr Lal Pathlabs too, the reason for high Goodwill as % of Capital employed is due to its asset light business.

Source: Companies, Marcellus Investment Managers

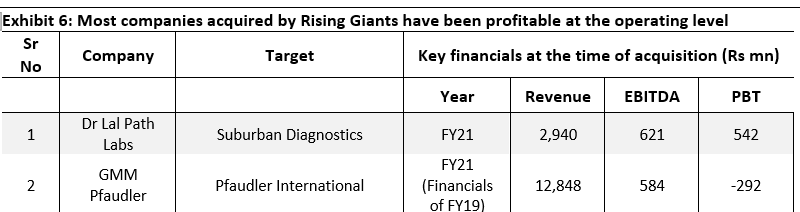

- Staying away from turnaround cases:Alongside rational use of leverage to fund an acquisition, another key aspect of Rising Giants companies’ inorganic strategy has been to stay away from turnaround bets. Most acquisition targets of Rising Giants have been companies already profitable at the operating level. Even in the case of GMM Pfaudler, the company has acquired the assets of loss-making companies like De Dietrich Process Systems and HDO Technologies and avoided acquiring the liabilities and the inefficient cost structure of these companies. Additionally, in both of these cases, the size of acquisitions is relatively small.

Source: Marcellus Investment Managers, Companies

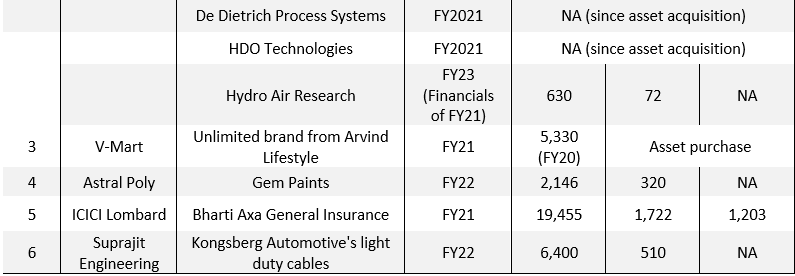

- Synergies with the existing business:Rising Giants companies’ acquisitions are mainly aimed towards increasing their product and service offerings in areas adjacent to their current offerings (‘soft diversification’) and/or to increase their geographical reach into newer markets. Such proximity of the acquired business to the legacy core business increases the chances of success. Please refer to the exhibit below for the rationale for the acquisitions made by Rising Giants companies.

Source: Marcellus Investment Managers, Companies

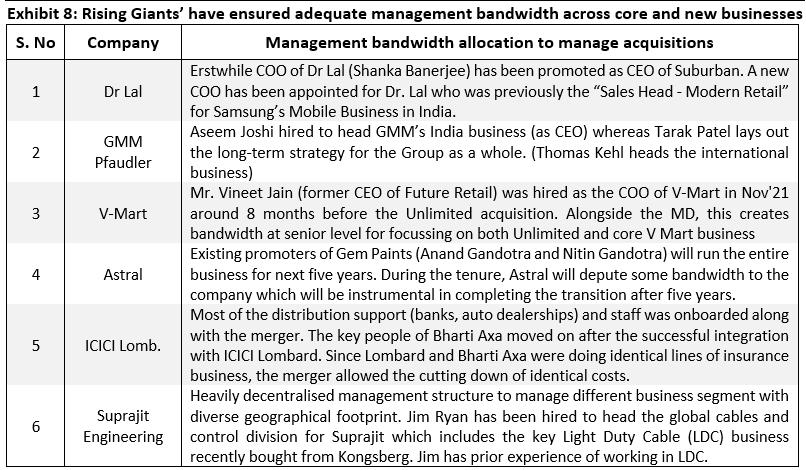

- Building management bandwidth to manage acquisitions:Management bandwidth allocation with sufficient delegation of responsibilities has been a key success factor for Rising Giants in integrating the acquisitions and managing businesses with diverse geographical footprints. It has also played an important role in executing the operational efficiency enhancements highlighted in the preceding bullet. There is a fair degree of incentivisation for the senior management through performance linked pay and in some cases stock options.

Source: Companies, Marcellus Investment Managers