OVERVIEW

Amongst registered Indian voters, more women today are voting than men. The rise in women’s active participation in politics (despite lower representation in Parliament) is a culmination of greater access to information and to business opportunities and greater availability of free time. All of these have been, in part, facilitated by positive policy changes. As more women realize the benefits from these policy changes and become financially independent, voter turnout for women is likely to rise further. This in turn will lead to further political empowerment thus creating a virtuous cycle.

“The right to equality in voting is a basic human right in liberal democracy. Women enjoy this right to equality in voting, and by casting a vote, they make a formal expression of their individual choice of political parties, representatives or of broad policies. The fact that more women are voluntarily exercising their constitutional right of adult suffrage across all states in India is testimony to the rise of self-empowerment of women to secure their fundamental right to freedom of expression. This is an extraordinary achievement in the world’s largest democracy with 717 million voters of which 342 million voters are women.” – Dr. Shamika Ravi in her essay titled Women and Electoral Politics: The Good, Bad and Ugly (2017)

Female representation in Parliament remains low

Kondagaon district (population of ~43,000 ) in Chhattisgarh is often characterized by Naxal uprisings and political turmoil. In this district, which is home to some of the most disadvantaged people in Indian society, resides Ms. Lata Usendi, a powerful woman with immense resolve. A seasoned politician, who also served as Minister of Women and Child Development in Chhattisgarh previously, Ms. Usendi has been actively involved in politics since 1998. And whilst she faced a setback in the 2018 state assembly elections to her rival, she continued working towards the betterment of people in the area. As a result, she contested the state assembly election from the same constituency again in 2023 and was elected. The grit and determination demonstrated by Ms. Usendi, her passion towards her profession, and her aspiration despite challenging circumstances, especially in the region that she comes from, is increasingly becoming the norm today in India.

Despite India implementing universal adult franchise (one vote per person regardless of their caste, creed, gender etc.) in 1947, political representation of women in the Indian Parliament has been very low. The number of women getting elected to the lower house of the Parliament (or Lok Sabha) grew at a meagre 2% CAGR over the last 20 years. As a result, even though the percentage of women elected from those who contested has gone down materially (meaning more women are contesting than they ever have been in history), the share of women across elected representatives in Lok Sabha has risen from 9% to just 14% during the same time period (see exhibit below). What this essentially indicates is that a higher number of women contesting elections is not translating into significantly higher number of women getting elected.

More Indian women are turning out to vote

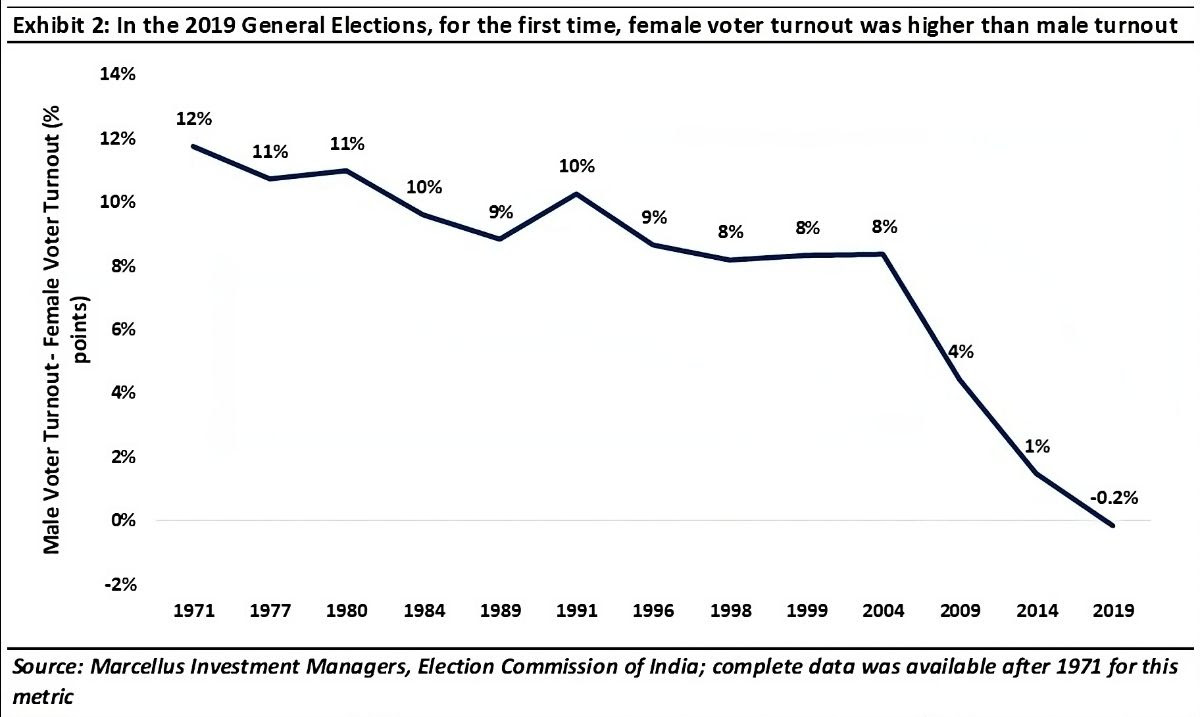

Interestingly, even as women’s representation as elected members of the Parliament has not improved, more women today than at any point in India’s history are exercising their right to vote. If we were to look at the Lok Sabha elections throughout independent India’s history, women voters as a percentage of all women registered to vote has reached its highest ever tally as of 2019 (in the previous Lok Sabha election). What is even more remarkable is that this ratio for women has already surpassed its equivalent for men in the country (as measured by Gender Gap ratio or the male voter turnout less female voter turnout); more women than men are exercising their right to vote with the Gender Gap ratio turning negative for the first time in 2019 (see exhibit below).

This dichotomy between lower representation of women in politics yet greater participation in the political discourse over the years, where more rather than less women are exercising their constitutional right to vote, naturally raises two questions – a) why did women start voting more than before, and b) what are its implications for the country going forward?

Improved access to internet and better educational outcomes for women

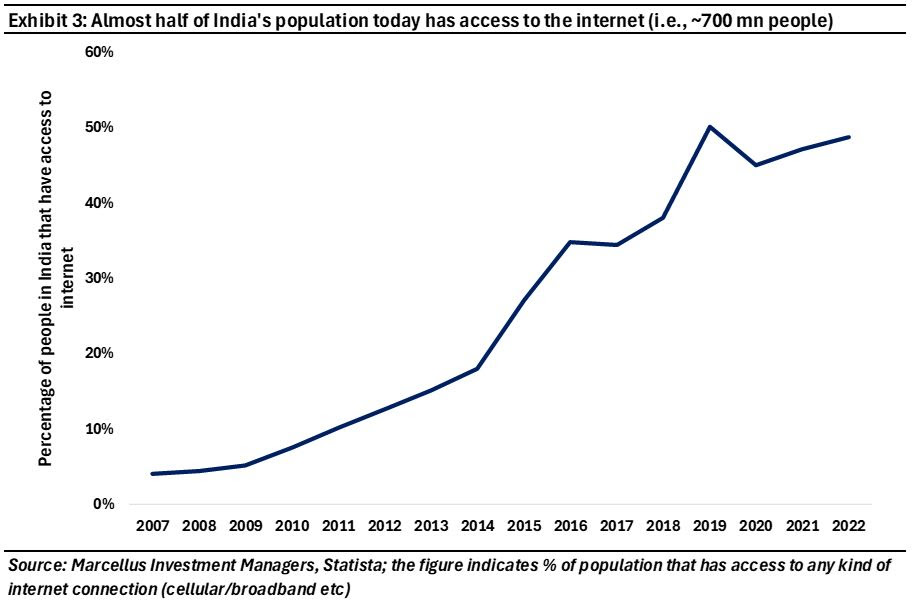

India’s story of joining itself up is one of hard work, vision, and perseverance. Nandan Nilekani, the erstwhile CEO of Infosys, began India’s journey towards a social security like number (Aadhaar) for all Indians. Aadhar was awarded to all citizens by 2014, followed by bank accounts in 2015 for all families under the Jan Dhan Yojana (enabled by Aadhaar), and then the proliferation of the internet – courtesy the entry of Jio in 2016 with its ultra low-cost internet – began (see exhibit below). This foundational trinity of India’s growth drivers is often dubbed as JAM (Jan Dhan, Aadhar and Mobile).

The last leg of JAM, that is widespread proliferation of smartphones and low-cost internet, has in turn laid the base for a variety of other facilities to be made available to every Indian. For instance, the introduction of the Unified Payments Interface (UPI) in 2016 made free financial transactions as easy as messaging someone. Just to contextualize how widely used this functionality is, the value of transactions exceed US$ 2 tn in calendar year 2023, which is more than half of India’s GDP!

We believe, women have disproportionately been able to capitalize on this change than their male counterparts. As we had explained in our previous note on the subject dated 11th January 2024, The Rapid Rise of Female Entrepreneurs in India, “Whilst the JAM trinity has enabled millions of Indians to lead better lives, women in particular have leveraged JAM very effectively to generate income. How so?

- Via their bank accounts, Indians now have access to Unified Payments Interface (UPI) that facilitates instant bank-to-bank money transfer (without any use of paper). UPI thus helps SMEs pay their suppliers and get paid by the customers instantaneously and with zero transaction costs.

- Given that Aadhaar numbers give Indians valid proof of residence and overall existence, Aadhaar eases the process of SMEs getting regulatory permits & licenses.

- Access to smartphones and cheap broadband (at 1/40th the cost prevalent in USA), helps Indian SMEs reach out to customers not just in their neighborhood but across the land via social media platforms like Instagram and YouTube thus increasing their total addressable market multifold.”

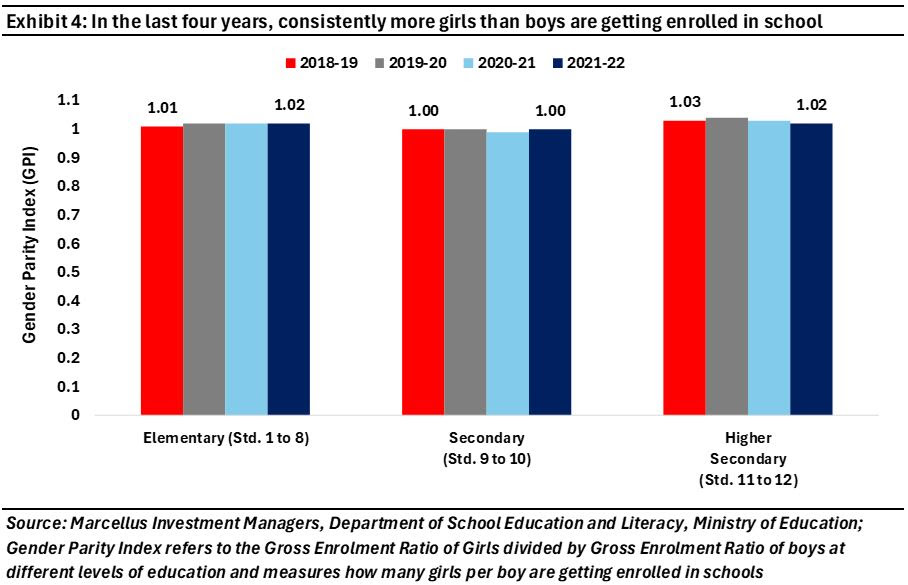

This coupled with the fact that more women are getting educated today with better outcomes (see exhibit below) creates a powerful phenomenon of greater access to women and the knowledge about how to leverage this access. In a way, hard work, vision, and perseverance that went into the creation of JAM is emblematic of Indian women, who are the torchbearers of these values across the country and at all levels.

Freeing up of time for women to engage in other activities of choice

“With the creation of scheduled part-time work in the 1940s and its enormous diffusion in the 1950s, the substitution effect became larger. Reinforcing factors include the almost complete diffusion of modern, electric household technologies, such as the refrigerator and the washing machine, and the previous diffusion of basic facilities such as electricity, running water, and the flush toilet” – Nobel Laureate Claudia Goldin in the Richard T. Ely lecture (2006)

In the United States, from 1920-40, thanks to the widespread diffusion of newly invented appliances that ran on electricity (a new innovation by itself then), household chores that took all day earlier now took only a fraction of the time. Women, who were at the time the primary agents holding responsibility for running their households, saw their physical strain and effort from managing these activities go down materially, leaving them with spare time to pursue other interests. And so emerged the working class American women who preferred to engage in part time work outside the households to earn wages. This is remarkable, as Claudia Goldin has explained, because in the years prior to this period whilst some women were engaged in work,, the “income effect” (i.e. the pressing need to earn more money) was the dominant reason why they would engage. In other words, they worked out of necessity. 1920-40 was the first time when women could choose to work, not out of necessity to sustain the household but by choice, shrinking the income effect and increasing the “substitution effect” (the effect that signifies women working and earning instead of men, rather than supporting the incomes earned by men).

India today appears to be at a similar stage of development as America was in the 1920s-40s. Most women in India spent most of their time on household chores, akin to their American counterparts from before the 1920s. This largely involves fetching water from distant sources, washing clothes manually, cooking with firewood and cleaning the house manually – all time consuming and laborious tasks. Thankfully, recent policy changes have changed the lives of Indian women for the better.

By 2018, all the census recorded villages in all the states had reported 100% electrification. Secondly, under the Pradhan Mantri Ujjwala Yojana (PMUY) roughly 80 million LPG connections were provided to below poverty line households by 2019 thus increasing the total LPG connections from ~140 million in 2014 to more than ~320 million as of March 2023.

Thirdly, under the Nal se Jal mission, roughly 145 million rural households (out of 190 million rural households in the country) have received tap water as of February 2024, up from 30 million in 2019.

These three changes alone have free up a significant portion Indian women’s time (time that was earlier spent on drawing water from faraway places, washing, cleaning and cooking). The freed up time in turn can now be used by women for more economically rewarding tasks.

Access to seed capital courtesy the government’s direct transfers

Both the central and state governments have floated multiple schemes targeted towards women, especially before elections, given that women voter turnout has been trending up over the last few election cycles. Worthy of mentioning amongst them are the schemes which directly transfer hard cash into the bank accounts of women (courtesy Jan Dhan) via Direct Benefit Transfer (DBT).

Schemes like Pradhan Mantri Matru Vandana Yojana (transferring Rs. 5000 to all pregnant and lactating mothers), Laadli Behna scheme in Madhya Pradesh (awarding each woman from 23 to 60 years of age Rs. 1000 per month in their Aadhaar linked bank accounts), Lakhpati Didi scheme in Rajasthan (provides interest free loans up to Rs. 5 lakhs to start business to earn a steady income), Karnataka government’s Gruha Lakshmi scheme (provides financial assistance of up to Rs. 2000 per month to women who have an impoverished background and are heads of their respective families) etc. are testament to governments across India’s states taking the rising trend of women voters seriously.

Impact #1: Economic and financial freedom for women

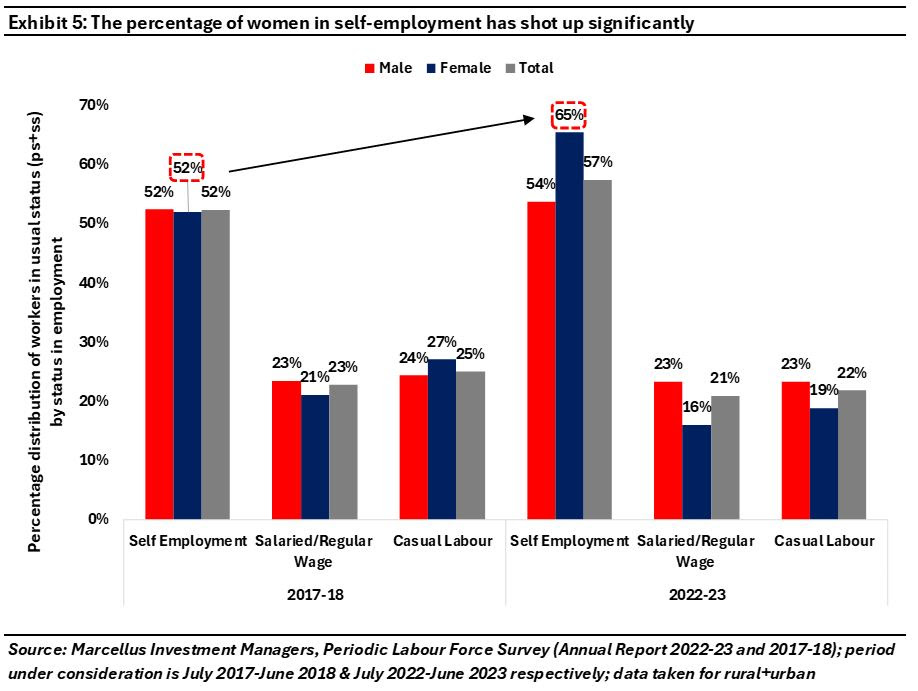

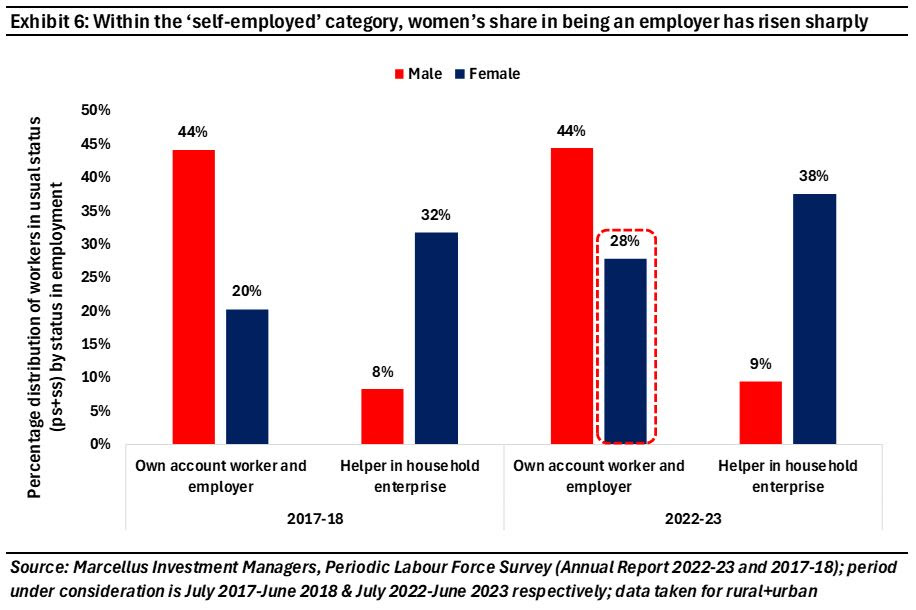

A major culmination of access to information, freeing up of their time, and access to seed capital has increased entry of women in the workforce. As per the latest annual Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) data, the Labour Force Participation Rate (LFPR) for women has risen to 37% from 23% in 2017-18. Furthermore, within LFPR, the rise in self-employment (see exhibits below) is testament to the effective use of resources to emerge as successful entrepreneurs even at the most micro (village or hamlet) level.

This has naturally led to women becoming financially independent and aware of their circumstances and rights. Having seen the fruits of the policy interventions through the years, and having felt the benefit personally, women are more likely to prefer policymakers who have helped them emerge financially and socially stronger.

Impact #2: Positive feedback loop of policy intervention at grassroot levels will drive greater political participation by women

The beauty and risk of the government’s schemes and policies at the grassroot level is: a) they are fairly easy to track; and b) they can be understood by the intended beneficiaries better because of improved education and awareness. As the three levers – access to information, freeing up of time to engage in financially rewarding activities, and access to capital – have started firing into tangible and measurable benefits for women, women in turn have started applauding the underlying policy changes, and are more likely to come out and vote to let this change continue into the future as well. As a result, an even higher voter turnout for women is expected in the forthcoming General Elections. This would in turn spur policymakers to deliver more benefits to their largest and fastest growing supporter base. Thus, a positive feedback loop is likely to emerge which not only materially improves the quality of life of India’s women but also brings into the Indian economy highly motivated and enterprising female entrepreneurs.

As this dynamic plays out in the country, we will continue to tilt our portfolios towards stocks where women are the main target customers. Stocks like Nestle, Titan, and Rainbow Hospitals already form a prominent part of several of our portfolios. Research is underway into more Indian companies whose products are aimed at the female consumer.

Nandita Rajhansa and Saurabh Mukherjea work for Marcellus Investment Managers (www.marcellus.in). Amongst the companies mentioned in this note, Titan, Nestle, and Rainbow Hospitals are part of Marcellus’ portfolios. Nandita and Saurabh may be invested in these companies and their immediate relatives may also have stakes in the described securities. The described stocks/securities are for educational/illustration purpose only and not recommendatory.

Note: the above material is neither investment research, nor investment advice. Marcellus does not seek payment for or business from this material/email in any shape or form. Marcellus Investment Managers Private Limited (“Marcellus”) is regulated by the Securities and Exchange Board of India (“SEBI”) as a provider of Portfolio Management Services. Marcellus is also a US Securities & Exchange Commission (“US SEC”) registered Investment Advisor. No content of this publication including the performance related information is verified by SEBI or US SEC. If any recipient or reader of this material is based outside India and USA, please note that Marcellus may not be regulated in such jurisdiction and this material is not a solicitation to use Marcellus’s services. All recipients of this material must before dealing and or transacting in any of the products and services referred to in this material must make their own investigation, seek appropriate professional advice. This communication is confidential and privileged and is directed to and for the use of the addressee only. The recipient, if not the addressee, should not use this material if erroneously received, and access and use of this material in any manner by anyone other than the addressee is unauthorized. If you are not the intended recipient, please notify the sender by return email and immediately destroy all copies of this message and any attachments and delete it from your computer system, permanently. No liability whatsoever is assumed by Marcellus as a result of the recipient or any other person relying upon the opinion unless otherwise agreed in writing. The recipient acknowledges that Marcellus may be unable to exercise control or ensure or guarantee the integrity of the text of the material/email message and the text is not warranted as to its completeness and accuracy. The material, names and branding of the investment style do not provide any impression or a claim that these products/strategies achieve the respective objectives. Further, past performance is not indicative of future results. Marcellus and/or its associates, the authors of this material (including their relatives) may have financial interest by way of investments in the companies covered in this material. Marcellus does not receive compensation from the companies for their coverage in this material. Marcellus does not provide any market making service to any company covered in this material. In the past 12 months, Marcellus and its associates have never i) managed or co-managed any public offering of securities; ii) have not offered investment banking or merchant banking or brokerage services; or iii) have received any compensation or other benefits from the company or third party in connection with this coverage. Authors of this material have never served the companies in a capacity of a director, officer, or an employee. This material may contain confidential or proprietary information and user shall take prior written consent from Marcellus before any reproduction in any form.