OVERVIEW

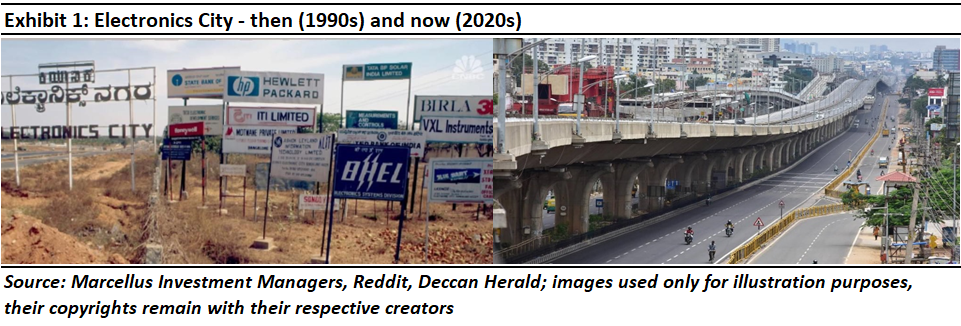

Three decades ago, the fortunes of two tiny villages ~20 kms away from Bengaluru changed for the better. In 1992, Infosys set up its campus in these villages and triggered a transformation in what is now known as Electronic City. This monumental change created winners (the tech companies, their employees, landowners) and losers (landless farmers, some SME owners). Understanding who they are helps explain much of what is happening in India today.

“We are much better off dreaming, taking risks, and trying to realize a billion aspirations; at best we risk falling flat on our faces. Far more egregious, and most dangerous to our country, is going about ‘business as usual,’ leaving a billion voices unheard and a billion frustrations unresolved.” – Nandan Nilekani, Chairman of Infosys, in his book ‘Rebooting India – Realizing a Billion Aspirations’ (2015)

Introduction

It was a typical summer in 1991 in Konappana Agrahara and Doddathogur, villages which are 20 km from the centre of Bangalore city. Farmers in these villages were busy sowing paddy and ragi, waiting for the upcoming monsoon which typically hits Karnataka by June. The monsoon arrived on time and filled the several reservoirs and lakes around these villages. That year, along with monsoon also came the economic reforms of 1991 which opened up the Indian economy and marked a major upshift in the country’s economic fortunes. In the summer of ‘91, unaware of just how dramatically these reforms would change their lives over the next few years, the farmers Konappana Agrahara and Doddathogur continued with the backbreaking effort which goes into tilling the land.

In 1991, a square foot of land in these villages cost Rs. 23. At the same point in time, land prices in city-centre Bangalore (now Bengaluru) and Bombay (now Mumbai) were Rs. 3,600 and Rs. 16,000 respectively (source: https://www.indiatoday.in/

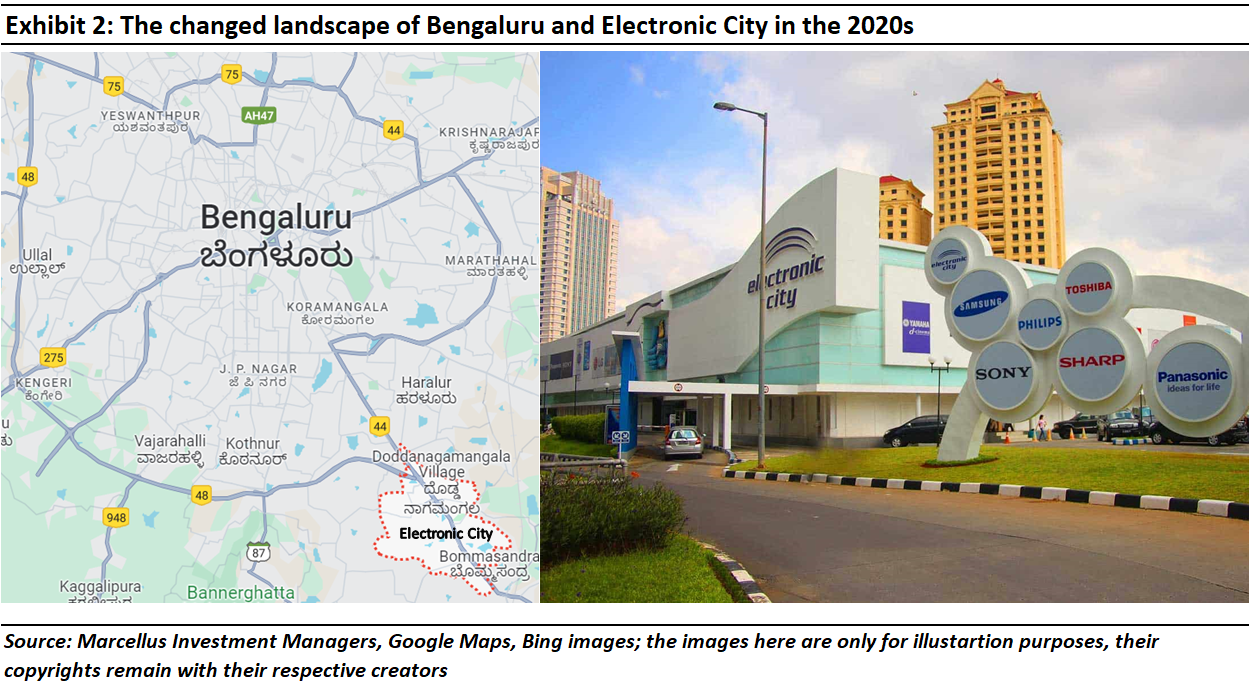

How did Konappana Agrahara and Doddathogur become Electronic City, home to the gleaming headquarters of prominent Indian firms like Infosys, Titan and Happiest Minds? There are broadly three phases in this story of transformation.

Phase 1 – Foundation of Electronics City in 1978

In the 1970s, whilst the ragi and paddy farmers in these villages went about their business, a man with a vision to make Bengaluru the next Silicon Valley, implemented the establishment of Electronic City. The man was Ram Krishna Baliga, chairman of Karnataka State Electronics Development Corporation (Keonics), who in 1978 established Electronics City on 332 acres of land from Konappana Agrahara and Doddathogur villages. Gradually, through the 1980s, this area became home to several electronics related manufacturing industries. However, it wasn’t until the liberalization of 1991 that the development of this area truly picked up pace.

Phase 2 – The reforms of 1991 and the entry of IT services in India

In the summer of 1991, then Prime Minister PV Narsimha Rao and his Finance Minister, Dr. Manmohan Singh, opened up the Indian economy to the world at large (refer to our 25th November 2023 blog for a fuller explanation of why this took place). These economic reforms breathed new life into the nascent IT services industry in India.

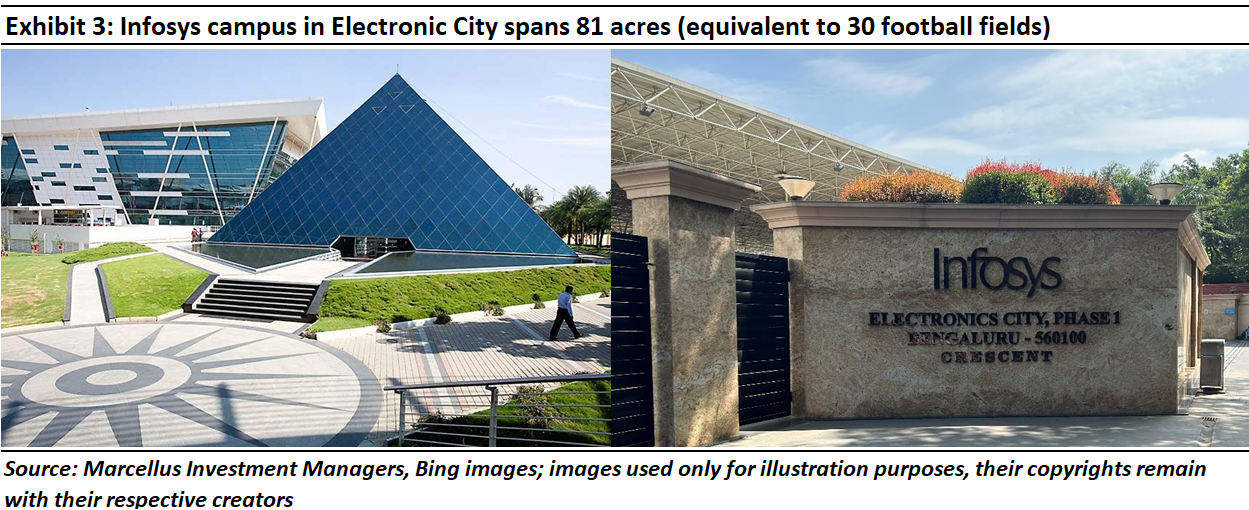

Established in 1981, Infosys, went public in 1992. As its business grew by leaps & bounds, Infosys needed larger offices and therefore purchased a large parcel of land from Keonics in Electronics City (roughly the area required for one and a half football fields). This is where Infosys’ first campus came up in 1993 (see the exhibit below for the colossal current day Infosys campus in Electronic City).

“Having acquired land from the state of Karnataka in Bengaluru, the company built a 160,000 square feet campus on five acres in a Software Technology Park in Electronics City and made it its headquarters. This prism-shaped structure is not merely a striking piece of architecture in the city, its inhabitants and corporate culture are of a standard and nature that has caught the attention of the world.” – excerpt from ‘N.R. Narayana Murthy: A Biography’ by Ritu Singh (2018).

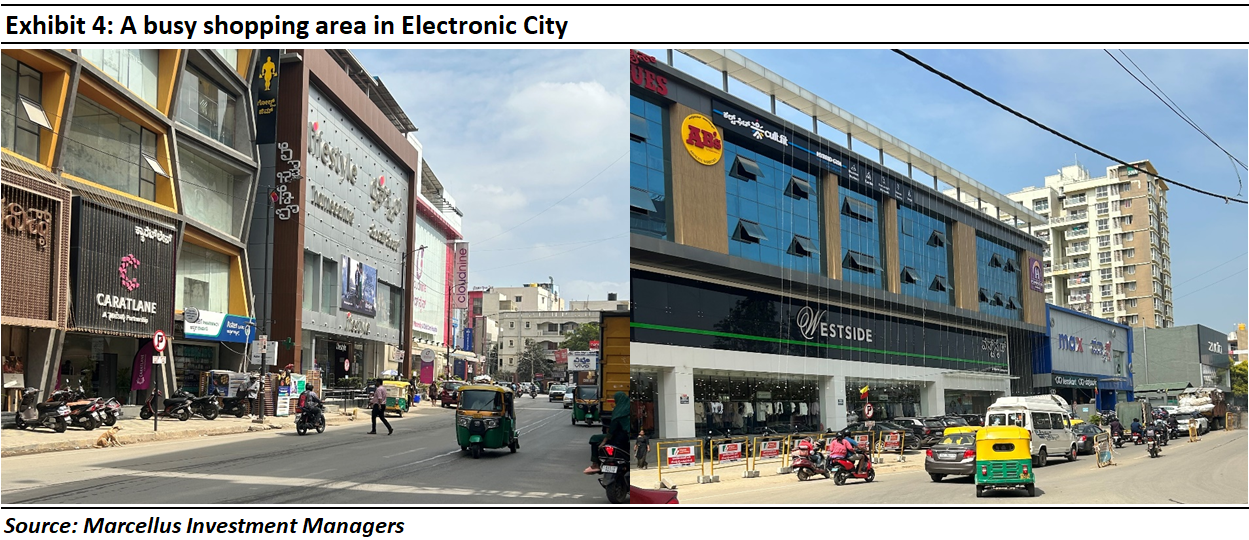

This event served as an inflection point for the area. After that, development in Electronics City went into hyperdrive. More companies started setting up their offices and campuses here. With these offices came tens of thousands of highly skilled white-collar workers. These workers and their families started settling down in the area around Electronics City.

Companies preferred this area because Bengaluru even then had excellent educational institutes like IIM (Bangalore) and the Indian Institute of Science. In addition, the longstanding presence of PSU giants – like Hindustan Aeronautics Ltd (HAL), Hindustan Machine Tools (HMT), Bharat Electronics Ltd (BEL), Defence Research & Development Organization (DRDO) and Indian Space Research Organization (ISRO) – meant that even in the early 1990s, Bengaluru had a large talent pool from which the IT services companies could draw their employees.

Just as importantly, the people in this city were largely welcoming to the migrant population that would continue pouring into the city in the decades to come. The residents of these two villages had no aversion to Hindi and easily assimilated both northern and southern cultures effortlessly into the social fabric of the newly emerging Bengaluru Metropolitan Region.

Phase 3 – Electronic City becomes a global IT hub in the 21st century

As India become the unchallenged IT services hub of the world through the first two decades of the 21st century, Electronic City boomed. According to the latest estimate available, Electronic City employs over 1 lakh people within its 3 square kilometres of area.

By 1997, the upkeep of Electronics City was transferred from Keonics to Electronics City Industries Association (ELCIA) and the development process gained further traction. ELCIA is an independent apex body serving the interests of all the electronic industries situated in the cluster. It not only represents the interests of all the companies that are situated in the area, but also provides skill development support, mentorship and hosts job fairs for the MSMEs in the area.

As more tech workers found employment in Electronics City, it drove a growing need for high-quality housing. This in turn led to the commissioning of Phase 2 of Electronics City in the late 1990s. Large residential projects started coming up in and around this area to cater to the demand. In what was once an area characterized by half a dozen lakes & reservoirs, water became scarcer as offices, apartments, roads & highways got built. To connect this booming tech hub with Bengaluru proper, a new elevated multi-lane road was inaugurated in 2010 – the Electronic City Elevated Expressway is a 10 km long elevated highway from the infamous (for its traffic jams!) Silk Board junction in Bengaluru city to Electronic City (the right-hand picture in Exhibit 1 shows the expressway).

So, who were the winners and losers as these tranquil villages became a booming tech hub over the course of three decades?

Three sets of big winners

The first set of beneficiaries from the development of Electronic City have been the Indian IT services firms as well as large MNCs who set up campuses here. They were able to get what is now prime real estate in Bengaluru Metropolitan Region at a bargain basement rate. For example, Infosys in 1992 acquired a large parcel of land in Electronic City for approximately Rs. 40 lakhs. Today, the price of the same piece of land (just the land) has risen 240x to roughly Rs. 100 crores. Infosys is just one of the more than 100 major employers in Electronic City (others include HCL Tech, Siemens, TCS, Texas Instruments, Hewlett Packard, Titan, and Wipro), almost all of whom have been able to build highly cost efficient and yet world class businesses locking into India’s skilled, low-cost talent combined with low-cost real estate.

The second set of beneficiaries are the people working in these companies. As demand for skills has boomed, the office workers in Electronic City have found many takers for their talents. In fact, if we look at the per capita income of the Bengaluru Urban district (which includes Electronic City), it has crossed Rs. 6 lakhs p.a., 3x the national average. Even Mumbai has not been able to keep up – per capita income in Mumbai is Rs. 3.44 lakhs, half the level of Bengaluru!

Income aside, the quality of life in Electronic City’s multi-cultural and multi-ethnic offices has resulted in the creation of a vibrant community of well educated, globally mobile and highly aspirational professionals. Watching day-to-day life pan out in Electronic City, one doesn’t need a degree in Economics or Sociology to realize that the next generation of India’s winners will emerge from the sort of intensely driven middle class families who live in these aspirational suburbs.

The third set of beneficiaries are the large landowners or landlords in the area. People who still own land in and around Electronic City have become rupee millionaires, courtesy the 240x escalation in land prices over the last 30 years. Assuming half of the area in Electronic City (roughly 450 acres out of the ~900 acres; note: 450 acres is roughly the land taken up by around 150 football fields) is with the landlords, where on an average the rent per month is Rs. 3 lakhs per acre, then each year the rent collection amounts to Rs. 160 crores ($20mn).

Let’s contrast this with the same amount of land being deployed in agriculture. One harvest of paddy will yield the farmer an in-hand profit of roughly Rs. 50,000 per acre, which means a total harvest profit of roughly Rs. 2.25 crores per annum (for the 450 acres of cultivable land in Electronic City). Assuming there are two harvest seasons in a year (paddy will not grow in both and prices will vary but for simplicity we are using this assumption), the total profit generated per annum will be Rs. 4.5 crores ($0.5mn), roughly 3% of what could’ve been earned had the same land been rented out to the big employers of Electronic City.

Who has lost as Electronic City boomed?

The first set of losers are the landless labourers who used to work in the farms of Konappana Agrahara and Doddathogur villages. With the farms gone, these labourers would have either had to relocate elsewhere into the interiors of Karnataka to continue earning a living in rural India or service the incoming migrant population by undertaking taxing day jobs like cleaning, sweeping, or cooking at meagre wages or head towards the factories of Hosur, Tamil Nadu, an industrial belt which is 25 km southeast of Electronic City.

The typical wage in a factory in Hosur is north of Rs. 4 lakhs per annum, significantly more than what a labourer in the farms of Karnataka earns today. Hence those labourers who have found employment in the industrial belts of south India, you could argue, are actually better off in the wake of their involuntary relocation from Electronic City. Unfortunately, the factories of south India employ in total just 6 mn workers. Hence there is a distinct probability that many of the landless labourers of Electronic City are continuing their struggle to earn a living in rural India.

As Electronic City developed with multiple companies setting up shop and employing affluent white-collar professionals, the associated cost of living in the area also rose rapidly: rental, food prices, transport costs, all surged. Whilst white collar professionals could afford this as their incomes rose at a much faster pace (thanks to pay hikes and promotions) than the rise in the cost of living, the landless labourers who had no specific skillset which gave them bargaining power in the labour market saw their incomes and savings dwindle in real terms i.e., after adjusting for inflation. Today, an annual income of Rs 2.5 lakh is enough for a comfortable life in rural south India but is barely enough to scrape by in an urbanized landscape like Electronic City.

The Rs. 6 lakh average per capita income of Bengaluru Metropolitan region is in this sense deceptive. According to the 2011 census, there were around 98,000 people classified as agricultural labourers (i.e., workers who do NOT own land) and around 95,000 as cultivators (i.e., farmers who own land), which makes it around 1% of the total population of the Bengaluru Urban district each. The standard of living of such people is likely to have fallen in a booming suburban district like Electronic City.

The uncertain winners

There is a third category of people in Electronic City whose benefit/loss arithmetic isn’t as clear cut as the previous two categories. These are largely the people involved in the intermediation trade i.e., local Kirana store owners, grain traders, 3W drivers or Small & Medium Enterprise (SME) owners. Their story in the new economic realities of modern India is not as straightforward as it was in the context of a village economy (i.e., a small and sheltered economy) where competitive intensity was lower, and they enjoyed better profit margins. This was the case in the pre-1991 era of Electronics City where small shop owners, auto drivers, and small business owners had complete control over the local economy and transportation system in that geography.

With the “opening up” of the Electronic City economy to external competition (from the wider Bengaluru region), the local monopolization benefits slipped away from these local small entrepreneurs with two sets of forces kicking in, at least in the retail space – the entry of organized and efficient players like D-Mart and e-Commerce platforms like Big Basket. This led to some loss of relevance, more than anything else, for the local Kirana stores as most of the migrant population in the city that did not have strong relationships built with them, inevitably started using the organized players’ services. Another example of this is how the local auto drivers’ lives have been upended by the entry of organized service providers like Uber and Ola in Electronic City. Even though today they are servicing higher number of passengers than they used to in pre-Uber/Ola days, they are not able to generate the same profit per ride that they once did.

Having said that, smart business owners and intermediaries have found ways to thrive in a booming urban area like Electronic City. As per Mr. Sumit Ghorawat, founder of ShopKirana – a B2B company that provides technology and supply chain management tools to retailers told us, “…any ordinary grocery retailer in most areas earns anywhere close to 10-15% gross margins on an average. Now whilst it may not be as high as that of established and larger chains like D-Mart or Star Bazaar, it’s enough for sustenance of the business.”

If over and above this, small retailers decide to go online and display their inventory to their customers on an app, they may be able to attract customers who are looking for particular products, enabling demand-supply matching. Furthermore, offering home delivery of products free or at a minimal charge will also help them squeeze out extra margins as people will prefer buying from nearby stores rather than driving all the way to far off locations. In a way, the ability to succeed for this class of SME now incrementally depends on their ability to find a niche and successfully service the clientele therein. If ONDC is able to scale successfully in India, the number of successful small business owners will burgeon.

Electronic City as a metaphor for India

Analogous to what happened in Electronic City post-1991, across India, companies that have built highly efficient and highly profitable businesses and engaged in prudent capital allocation over the years have benefited disproportionately. India’s shift from misguided socialism to pragmatic capitalism bodes well for these giant enterprises. As we have noted in one of our previous notes dated 24th December 2022, ‘Winner Takes All’ in India’s New, Improved Economy, “Capitalising on the exponential surge in digital transactions and the massive improvements in transport infrastructure and market structure seen over the past decade, a handful of Indian companies – no more than 20 – are taking home ~80% of the profits generated by the Indian economy. Simultaneously, a mere 20 companies account for 80% of the $1.4 trillion of wealth created by the Nifty over the past decade…

In the decade ending 31st March 2012, the Nifty added around $440 bn in market cap. In these ten years, ~80% of the value generated came from 17 companies and the median Total Shareholder Return (TSR) CAGR was 26% for these 17 companies. Moving forward by a decade, in the decade ending March 31st, 2022, the Nifty added ~$1.4 trillion in market cap. And 80% of the value generated in these ten years came from just 20 companies whose median TSR CAGR was 18%.”

At the opposite end of the spectrum, every year around 10,000 SMEs are shutting down in India (see for example this article for data about more than 12,000 MSMEs shutting down in FY23). Once upon a time, smaller companies used to be able to survive on tax evasion at multiple levels (payroll taxes, indirect taxes, direct taxes on profits and direct taxes on the proprietor’s income). With the rise of UPI, GST and the India Stack, such tax evasion has become increasingly difficult for smaller companies. After paying full taxes, it becomes harder for these companies to compete with their larger competitors who have the best talent, the cheapest capital, the cheapest land and the greatest access to the corridors of power.

Nandita Rajhansa and Saurabh Mukherjea work for Marcellus Investment Managers (www.marcellus.in). We thank Naren V.P. for his help in pulling this note together. Amongst the companies mentioned in this note, Infosys, Tata Consultancy Services, Titan Company, and Star Bazaar (Trent) are part of Marcellus’ portfolios. Nandita and Saurabh may be invested in these companies and their immediate relatives may also have stakes in the described securities.

If you want to read our other published material, please visit https://marcellus.in/pms-investment-blog/

Note: the above material is neither investment research, nor investment advice. Marcellus does not seek payment for or business from this material/email in any shape or form. Marcellus Investment Managers Private Limited (“Marcellus”) is regulated by the Securities and Exchange Board of India (“SEBI”) as a provider of Portfolio Management Services. Marcellus is also a US Securities & Exchange Commission (“US SEC”) registered Investment Advisor. No content of this publication including the performance related information is verified by SEBI or US SEC. If any recipient or reader of this material is based outside India and USA, please note that Marcellus may not be regulated in such jurisdiction and this material is not a solicitation to use Marcellus’s services. This communication is confidential and privileged and is directed to and for the use of the addressee only. The recipient, if not the addressee, should not use this material if erroneously received, and access and use of this material in any manner by anyone other than the addressee is unauthorized. If you are not the intended recipient, please notify the sender by return email and immediately destroy all copies of this message and any attachments and delete it from your computer system, permanently. No liability whatsoever is assumed by Marcellus as a result of the recipient or any other person relying upon the opinion unless otherwise agreed in writing. The recipient acknowledges that Marcellus may be unable to exercise control or ensure or guarantee the integrity of the text of the material/email message and the text is not warranted as to its completeness and accuracy. The material, names and branding of the investment style do not provide any impression or a claim that these products/strategies achieve the respective objectives. Further, past performance is not indicative of future results. Marcellus and/or its associates, the authors of this material (including their relatives) may have financial interest by way of investments in the companies covered in this material. Marcellus does not receive compensation from the companies for their coverage in this material. Marcellus does not provide any market making service to any company covered in this material. In the past 12 months, Marcellus and its associates have never i) managed or co-managed any public offering of securities; ii) have not offered investment banking or merchant banking or brokerage services; or iii) have received any compensation or other benefits from the company or third party in connection with this coverage. Authors of this material have never served the companies in a capacity of a director, officer or an employee.

This material may contain confidential or proprietary information and user shall take prior written consent from Marcellus before any reproduction in any form.