Over an extended period of time, it is hard to make money in Retailing. In this newsletter, we discuss a subset of retailing – apparel retailing – and how the principles that underpin the business models of consistent compounders in general are of relevance for success in apparel retailing as well. Two key variables – ‘percentage of discounted sales’ and ‘inventory turnover’ – determine a retailer’s ability to generate heavy cashflow from its operations. Retailers like Trent – a recent addition to our portfolio – have used product relevance & store level execution to achieve industry leading metrics. Additionally, successful retailers reinvest their profits to expand their profitable business segments and incubate new, highly profitable product categories – creating the cycle that leads to consistent compounding of wealth for shareholders.

“Retailing is a tough business. During my investment career, I have watched a large number of retailers enjoy terrific growth and superb returns on equity for a period, and then suddenly nosedive, often all the way into bankruptcy. This shooting-star phenomenon is far more common in retailing than it is in manufacturing or service businesses. In part, this is because a retailer must stay smart, day after day. Your competitor is always copying and then topping whatever you do. Shoppers are meanwhile beckoned in every conceivable way to try a stream of new merchants. In retailing, to coast is to fail.”- Warren Buffet in his 1995 letter to shareholders

Consumer retail is a difficult sector to make money in

A casual observer of India’s bustling malls and retail outlets – especially in the festival season – may imagine that consumer retail must be a profitable business to be in. However, as is often the case in the investment world, reality is more nuanced than what’s readily visible to the naked eye. In our May’21 newsletter, we’d discussed how it’s extremely rare to find a cash generative retailer in India:

“India’s retail industry is more than US$700bn in size. However, less than 20% of the industry is organized, even though it has been more than two decades since large-store pan-India retail formats (like departmental stores and supermarkets) started expanding, and more than three decades since small-store pan-India retail formats (like Bata) have existed in the country. The balance 80% of the industry continues to be traditional mom-and-pop shop formats.

Furthermore, over the past 10 years, only a small fraction of the organized retail industry in India has managed to deliver returns on capital (ROCE) more than cost of capital whilst also growing the retail network at a healthy pace.”

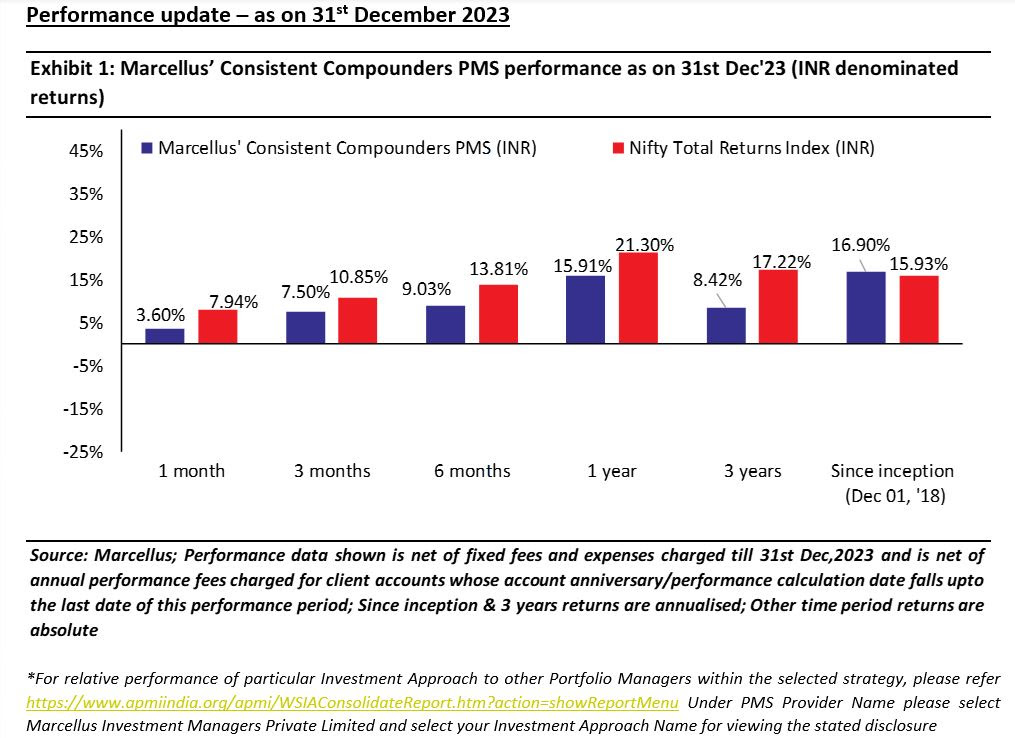

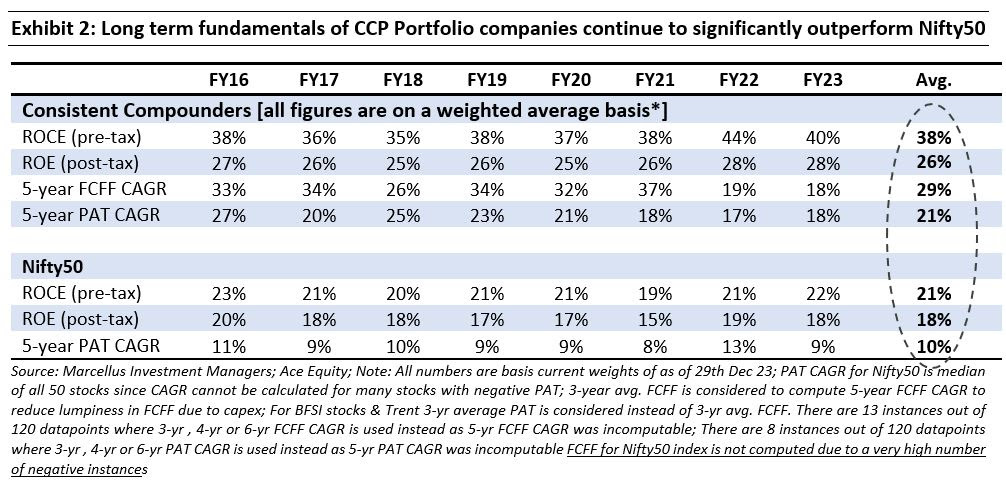

Over the past few years, Marcellus’ Consistent Compounders Portfolio (CCP) has had exposure to two retail companies – Titan (retail formats for jewelry, watches, eyewear etc.) and Dr. Lal Pathlabs (diagnostic company with retail based operations – labs and collection centres). In August 2023, we added another retail firm – Trent Ltd. (an apparel retailer transitioning to a platform of multiple formats) to our portfolio.

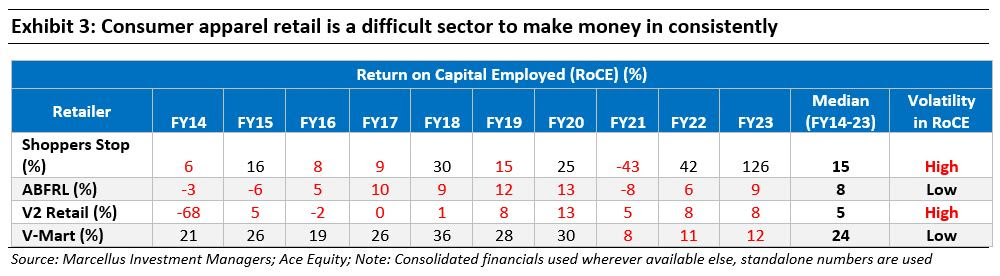

In the apparel retail space, the listed players have a rather grim history. As can be seen in the table below, barring V-Mart (which has struggled only in the post-Covid era), most apparel retailers have struggled to consistently generate RoCE greater than their cost of capital (which we assume to be around 15%).

What does it take to become a successful apparel retailer?

“The average Helzberg’s store has annual sales of about $2 million, far more than competitors operating similarly sized stores achieve. This superior per-store productivity is the key to Helzberg’s excellent profits. If the company continues its first-rate performance – and we believe it will – it could grow rather quickly to several times its present size.” – Warren Buffet on Helzberg’s Diamond Shops in his 1995 letter to shareholders (underline added by us)

The path to becoming a successful retailer is very similar to the path to becoming a consistent compounder in any industry. As we’d discussed in our May’23 dated newsletter, there are two key components which work together to achieve decadal compounding:

- Firstly, RoCE determines if a business creates shareholder value or not (i.e. if Return on capital > cost of capital then the business generates shareholder value); and

- Secondly, the reinvestment rate determines the growth rate and longevity of the business.

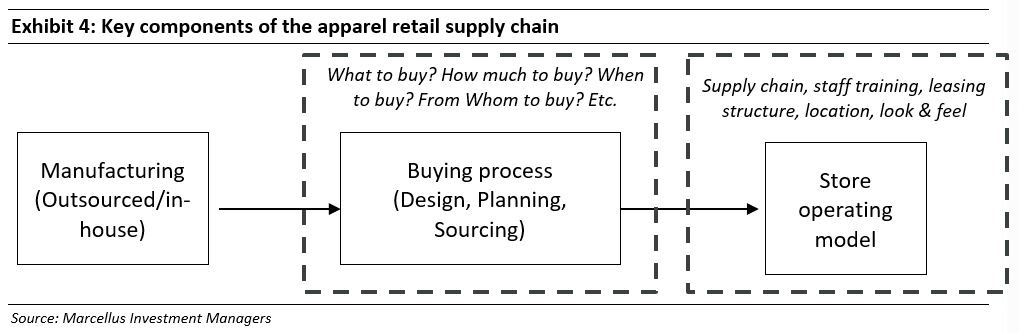

An apparel retail supply chain can be summarized as shown in the chart below.

A retailer typically makes money by earning a margin on the merchandise its procures and sells to the end customer. Such merchandise can be either sold under its own private labels or as 3rd party brands. Further, the retailer can either own the retail outlets and have full control over the display, product placement and other aesthetics of the store or work in a franchise model. Getting the store right is certainly important for the retailer, but the key source of competitive advantage lies in the “Buying process” (the middle box).

The “buying process” is responsible for providing ‘relevance’ to the customer (through a combination of relevant design, quality and price). This creates brand equity, customer loyalty and more importantly ability to deal with competition. The strength of such a “buying process” is reflected in the Return on Capital Employed metric for a retailer. Let’s understand how.

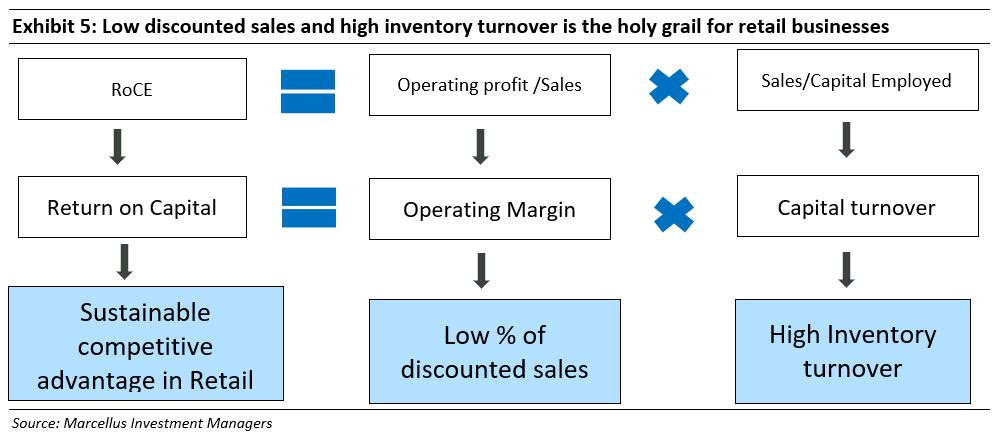

The Return on Capital Employed (RoCE) of a retailer can be broken down as shown below:

- The first term of the equation shaded in blue reflects the retailer’s bargaining power with its suppliers as well as its pricing power vs. the customer. All else equal, the bigger the gap between the cost of procurement and sales price, the higher the operating margin.

- The second term reflects the retailer’s ability to effectively use its capital (the store, employees, etc.) to sell its merchandise. All else being equal, a retailer who is able to sell through more merchandise and churn its inventory faster has a higher capital turnover.

For a retailer these two terms essentially translate into – percentage of discounted sales (related to first term) and the inventory turnover (related to the second term)

Many successful retailers choose to focus on one of the two items. For e.g.

- Vedant Fashions which sells Indian ethnic wear under the Manyavar brand has high margin but relatively low inventory turnover, and

- V-Mart has relied on high inventory turnover while keeping its margins modest. In grocery retailing, D-Mart has also following a similar approach.

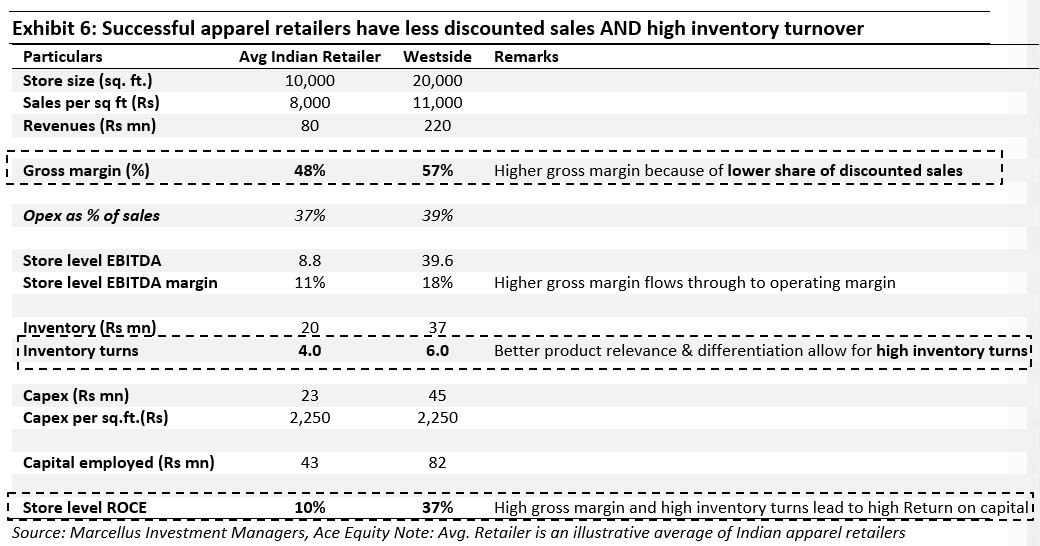

However, if a retailer can combine BOTH these traits i.e. ensuring high inventory turnover alongside ensuring a low percentage of discounted sales, that points to a huge competitive advantage and lays the ground for sustainably high RoCEs. Trent Ltd. combines these traits in its retail operation. The table below showcases how its store level unit economics is superior vs. its peers. [Note: Westside is Trent’s offering aimed at middle class customers.]

In the mass apparel segment that Trent operates in, its key source of moat is in the form of product relevance. If the product is differentiated through quality and design & priced correctly, a company can maximize its “full priced” sales – essentially not resort to liquidating unsold inventory at a discount every and thus reducing its margins (recall the first term in the blue shaded equation).

Such product differentiation is possible only when the retailer has a strong understanding of customer requirements which in Trent’s case is enabled through granular customer segmentation and high-quality designers and store level execution. Trent does this successfully through its store operating model (supply chain, staff training, leasing structure, store location, look & feel).

Additionally, quick refreshment rates (every 15 days or so) allows for low inventory levels in stores – leading to high Inventory turnover ratio (recall the second term in the equation we presented earlier). In other words, consistently relevant & differentiated product = less dead stock = less discounted sales & high inventory turnover.

How do successful retailers increase the longevity of wealth creation?

To be a successful retailer (i.e. to be a Consistent Compounder) it’s not enough to just be operationally excellent in a given segment at a point of time. A core necessity for compounding over decades is the ability to reinvest internally generated cash towards scaleup of profitable business segments as well as addition of new highly profitable categories for future growth.

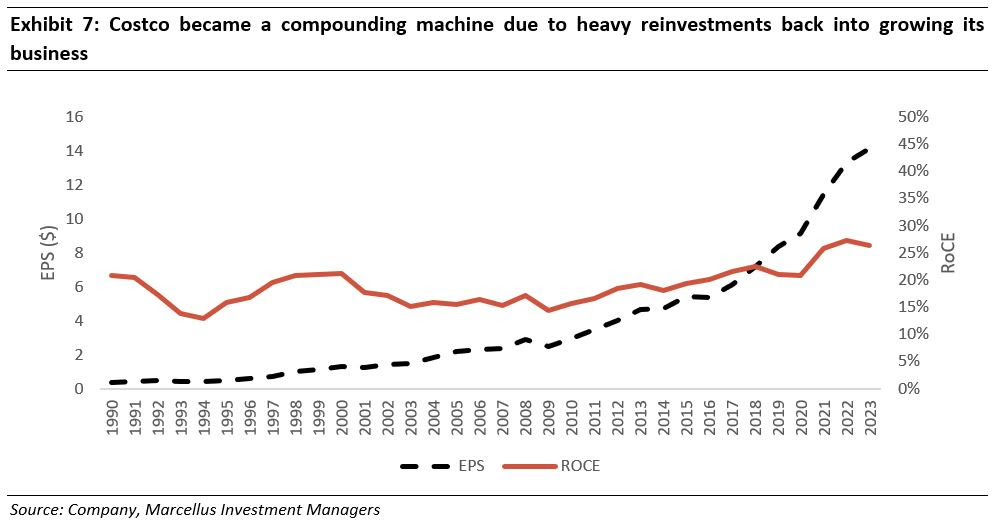

Highly successful grocery retailers like Costco (a part of our Global Compounders Portfolio) have been doing this for many decades. As can be seen in the chart below, the marquee retailer has kept it’s RoCE above 15% through the last 30+ years while growing its EPS by ~37x (1990-2023). The profit growth was a result of reinvestment into increasing store count which went from just 119 in 1990 to 861 in 2023 as well as into garnering higher share of private labels (12% in 1999 to 30% in 2021)

Back in India, Titan – a CCP holding – has similarly reinvested its profits back into the expansion of its existing brands like Tanishq (52 stores in FY02 to 423 stores in FY23) as well as towards the addition of new brands like Titan Eye Plus (14 stores in FY08 to 896 stores in FY23) and Caratlane (55 stores in FY19 to 222 stores in FY23). It continues to add new brands like Zoya and Taneira to keep the compounding flywheel turning.

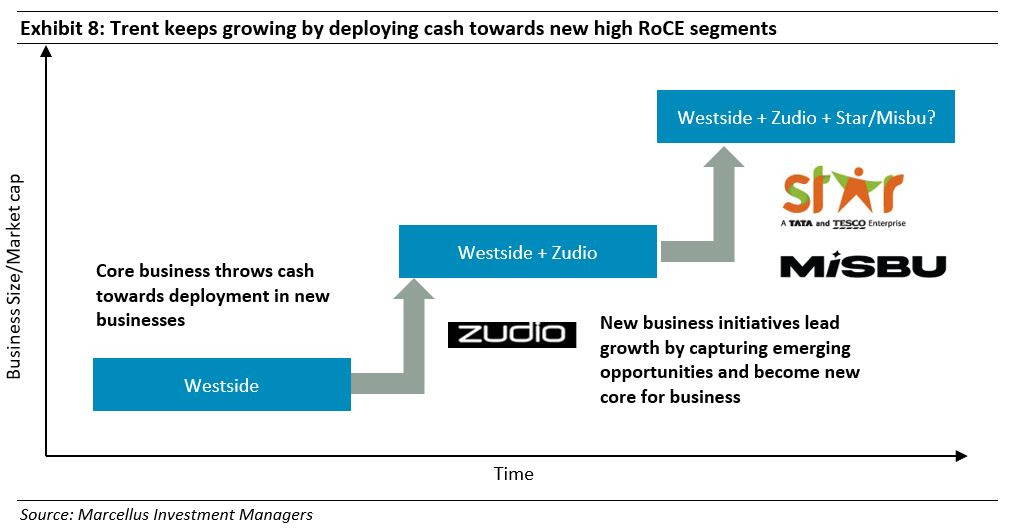

Trent too is embarking on a similar trajectory with the expansion of its Westside stores as well as addition (and scale-up) of new formats like Zudio, Star and Misbu.

Westside’s store count has gone from 70 in FY13 (the year it became profitable) to 214 in FY23. The cash generated from Westside was being (and is being) used to expand Zudio stores once the format became self-sustainable. The Zudio store count has gone from just 7 in FY18 to 352 in FY23. We expect the company to follow similar ‘fast scale up of profitable business’ approach in new brands like Star Bazaar and Misbu as well.

Investment Implications:

Retailing is a difficult sector to make money in consistently over long periods of time. A corollary of this aspect is that the very few retailers are able to crack the code of consistent wealth compounding over long periods of time. The CCP portfolio aims to identify such retailers in the Indian ecosystem which have a long runway for value accretive growth. Retailers in our portfolio – like Titan and Trent – have been able to differentiate themselves vs. their peers through tight control on product quality as well as inventory management allowing them to grow at a good pace without sacrificing returns on shareholder capital. We remain confident and excited about the future prospects of these companies and that they will play a big part in our investors’ wealth creation journey.

Regards,

Team Marcellus

If you want to read our other published material, please visit https://marcellus.in/