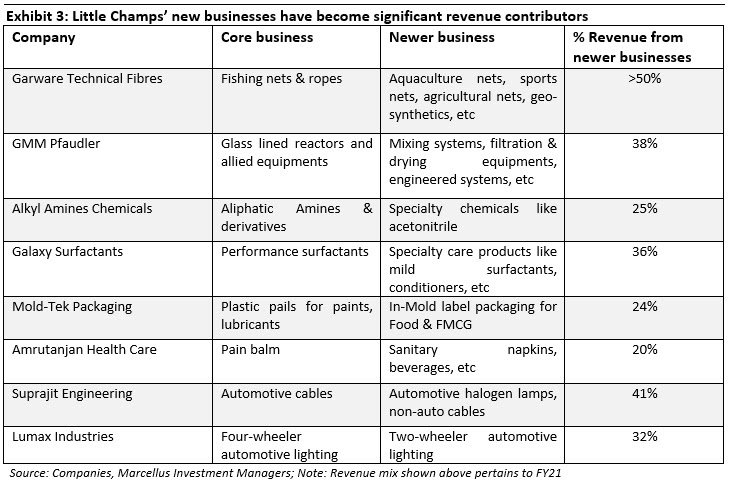

Alongside globalisation (see our July ‘21 newsletter), diversification has been an important feature of Little Champs’ growth strategy. Unlike what we see in the broader corporate world, Little Champs’s diversification strategies have been successful with new forays over the past decade now contributing in excess of 20% of revenues for most portfolio companies and RoCEs sustaining at healthy levels. So, why have Little Champs succeeded in an area where most of India Inc has failed? Key success factors are the ‘soft/related’ nature of diversification (strong linkages of the new businesses to the core business in terms of product, manufacturing process and/or distribution), measured capital allocation and effective organisational allocation of limited management bandwidth.

Performance update for the Little Champs Portfolio

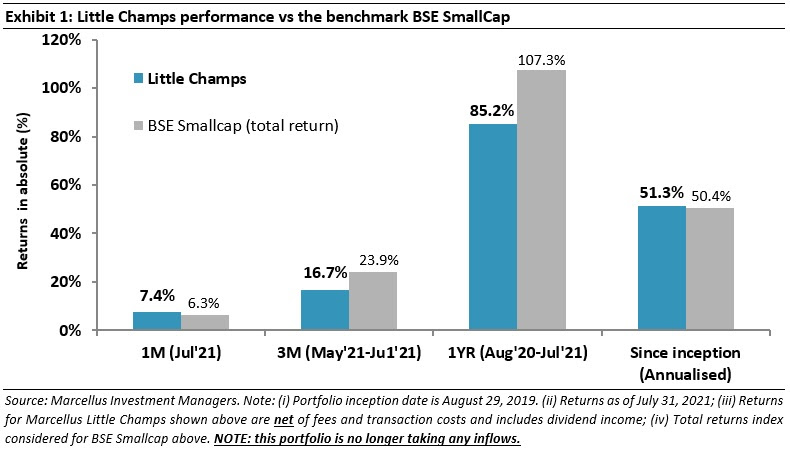

At Marcellus, the key objective of our Little Champs Portfolio is to own a portfolio of about 15-20 sector leading franchises with a stellar track record of capital allocation, clean accounts & corporate governance and at the same time high growth potential. While we intend to fill our portfolio with winners, we want to be sure of staying away from dubious names where we are not convinced about the cleanliness of accounts or the integrity of the promoters (even though business potential may sound promising) as the fruits of company’s performance may not get shared with minority shareholders. We intend to keep the portfolio churn low (not more than 25-30% per annum) to reap the benefits of compounding as well as minimize trading costs. The Little Champs Portfolio went live on August 29, 2019. The performance so far is shown in the below table.

Diversification – Little Champs’ key strategy to mitigate growth challenges

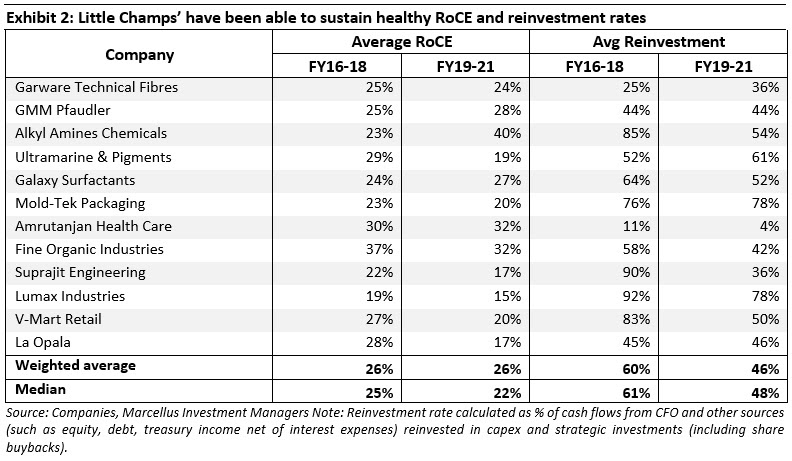

Little Champs with their deep-rooted competitive advantages deliver returns on capital employed (RoCE) substantially higher than their cost of capital. This results in strong operating cash generation for these companies. However, high RoCE and cash generation by themselves would not be of much use if the company is not able to find avenues to redeploy the surplus cash flows at the current high levels of RoCE. In this regard, Little Champs are an exceptional set of small cap companies which have been able to sustain a combination of high RoCEs and high reinvestment rates over long periods of time.

The performance shown in Exhibit 2 is despite: (i) the macroeconomic challenges of the recent years where economic growth has been weak; and (ii) the Little Champs operating in niche industries where growth becomes a challenge particularly once a company achieves a high market share. In our July 2021 newsletter, we mentioned that Little Champs have managed to sustain high growth rates (and profitably reinvestment their surplus cash) on the back of two broad strategies – globalisation and diversification. We discussed the globalisation strategy in detail in last month’s newsletter. We will focus on diversification in this month’s newsletter.

It may be noted that globalisation and more particularly diversification – as tools for driving growth – are not unique to Little Champs but have been used widely used across the corporate world. However, as is the case with globalisation, only a few Indian companies have been able to make a success out of diversification measured in terms of size, profitability, return on investment, etc. In fact, in our recently published blog (Link), we explained using Jim Collins’ ‘Five stages of decline’ framework that many companies, hitherto successful, fueled by hubris and arrogance pursue undisciplined diversification which ultimately leads to their downfall. Unfortunately, this is true for most companies as is visible in the high churn ratios of the benchmark indices like Nifty50 and BSE500.

On the other hand, as can be seen in the below exhibit, most Little Champs’ diversification attempts have been broadly successful creating strong additional growth drivers for the companies over the past decade.

|

|