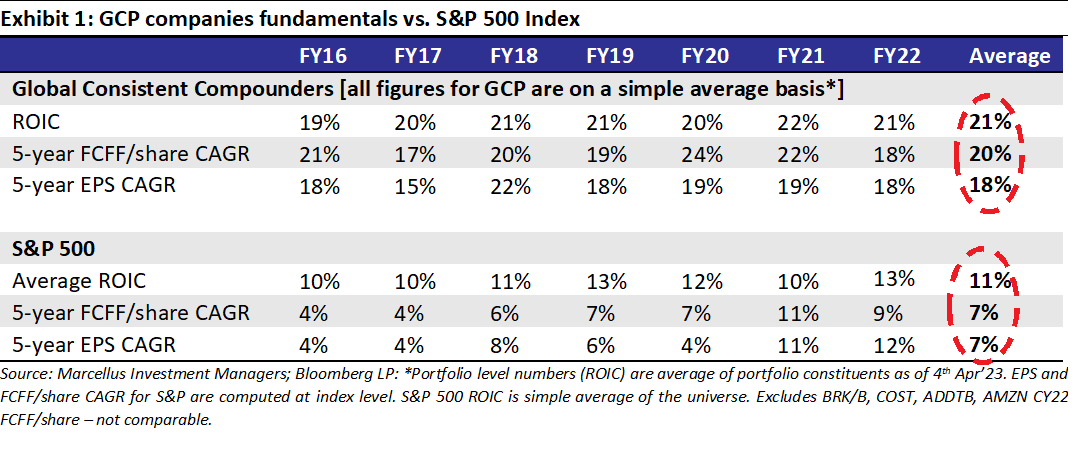

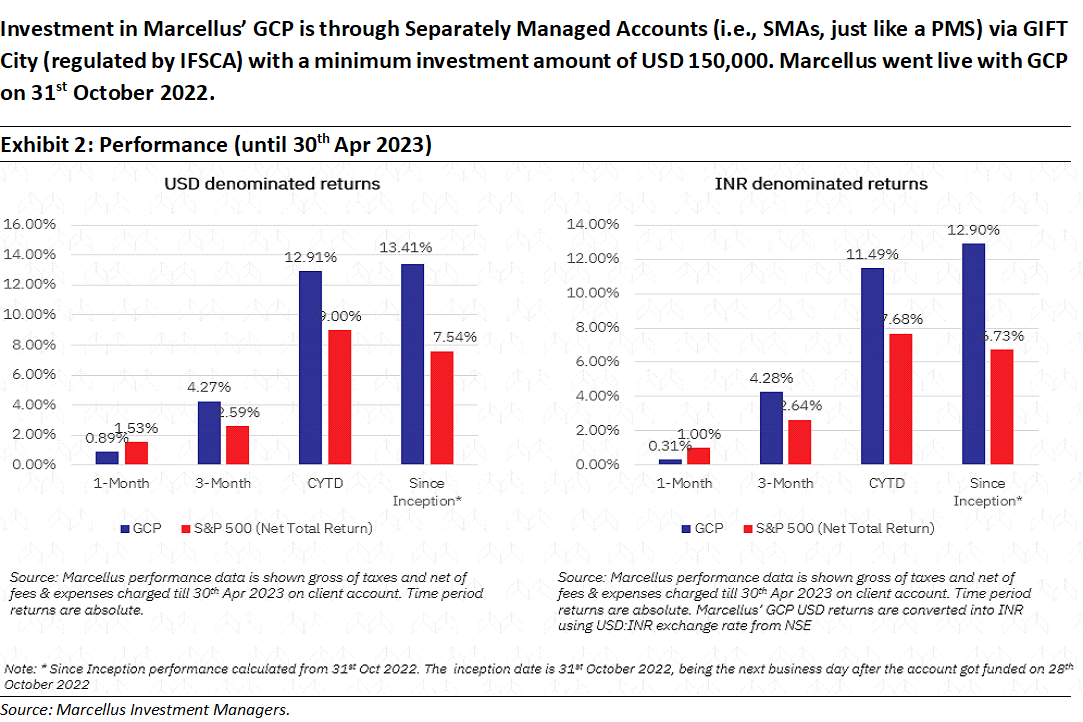

Marcellus’ Global Compounders Portfolio (GCP) invests in 25-30 deeply moated global companies which are listed in developed countries. The nature of the products and services – which cater to global economic megatrends – and the moats developed around process capacity, R&D, and capital allocation, are the key factors that contribute to the consistency of free cashflow compounding for GCP companies. Free cashflows per share have increased at a rate of roughly 20% (USD) per annum for GCP companies. In this note we explain why luxury goods manufacturers with deep moats are a key component of GCP.

Portfolio Fundamental Characteristics:

The GCP Introductory newsletter deeply discusses how Marcellus’ GCP was conceptualized and constructed. In the newsletter, we focus on a specific subset of the portfolio – luxury goods manufacturers. Companies such as Hermes in our portfolio provide products which can be deemed to be ‘Luxury’.

Investing in the global luxury sector offers potential benefits due to its historical resilience during economic downturns, growing demand from emerging economies, and the enduring brand power of luxury goods manufacturers. Additionally, the sector encompasses luxury experiences beyond physical products, providing opportunities for diverse investment avenues. In day-to-day parlance, however, the terms ‘Luxury’ and ‘Premium’ are used interchangeably. As we explain in this newsletter, not only are there differences between the two terms, investing in luxury goods manufacturers is a far more rewarding proposition.

“Affordable luxury – these are two words that don’t go together” – Bernard Arnault, CEO of LVMH

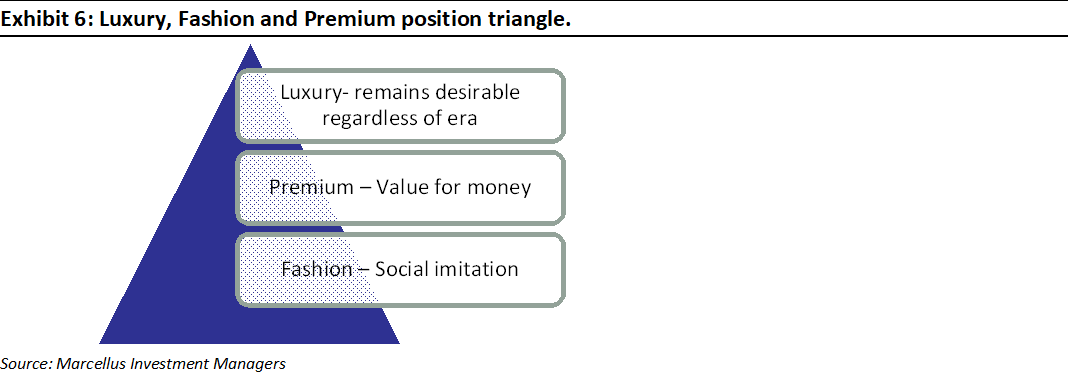

‘Luxury’, ‘Premium’ and ‘Fast Fashion’ – these are three mutually exclusive concepts in consumption. Drivers of competitive advantages for companies selling products in these three categories are also mutually exclusive.

For example, BMW is often talked about as a ‘luxury’ car brand when it is actually a ‘premium’ car brand. A high-quality engine, a wide range of features and driving comfort does not define a ‘luxury’ car. Luxury cars are often built by brands with long-standing luxury pedigree (think Rolls-Royce, Bentley, Aston Martin, etc.), whereas premium car brands tend to be “mainstream” companies that also build more affordable models (like Audi, BMW, Mercedes, etc.). To be more specific, the consumer orientation of a luxury, premium and fashion product can be segregated as –

1) Luxury: Anything that indicates wealth, status, and taste is luxury. It is meant for individuals who want to display their elite social standing. Examples – Hermes, Ferrari, Lamborghini.

2) Premium: A premium offering aims to provide a higher level of quality in proportion to its price i.e., better value for the price you pay. Example – Guess, Hugo Boss, BMW.

3) Fast Fashion: Follows a popular trend or style. Here the consumer is not trying to indicate that she’s an UHNW; she’s simply signaling her awareness of the latest trend. Example- teenagers buy trendy outfits from Zara, H&M and Primark without splurging too much money.

Luxury and Premium brands are managed using distinct strategies.

Management teams lacking clarity around the differences between these two segments have historically made mistakes as explained in the case study below.

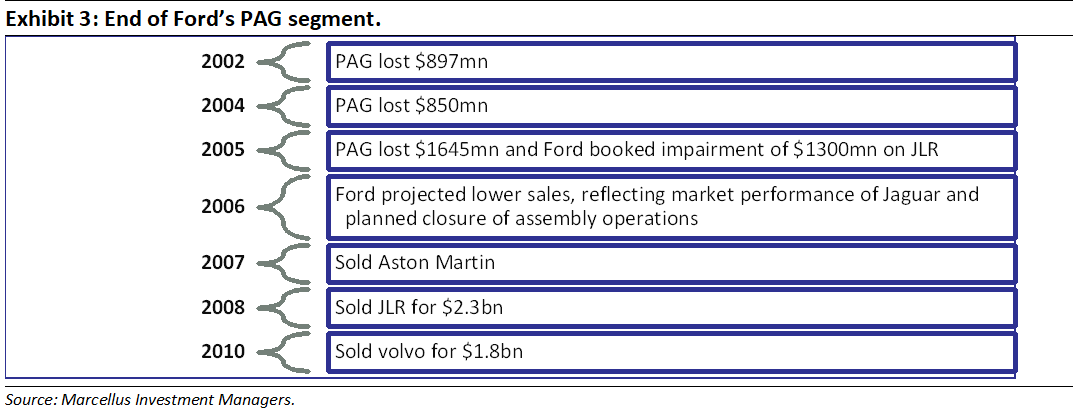

Case study of Ford – During the late 1990s and early 2000s, Ford Motor Group established and expanded the Premier Automotive Group (PAG), a luxury car segment that included renowned brands acquired by Ford in earlier years. These brands comprised Volvo from Sweden, as well as Jaguar, Land Rover, and Aston Martin from Great Britain. Despite a substantial investment of at least $17 billion over 15 years, PAG failed to achieve profitability. Unfortunately, Ford’s board overlooked the significance of these brands’ heritage and the unique characteristics, target audiences, and dealership networks associated with each. As a result, Ford discontinued the PAG segment within a few years and sold most of the brands for less than half their original purchase price.

To illustrate the problems encountered, let’s focus on Jaguar specifically. In 1989, when Ford Motor Company acquired Jaguar, it aimed to gain a share of the lucrative European luxury car market. However, neither Jaguar nor the other brands acquired by PAG ever managed to turn a profit under Ford’s ownership.

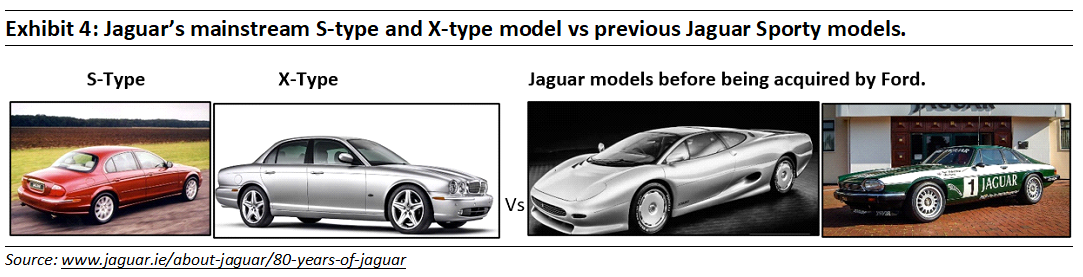

Jaguar was renowned for its sportiness and speed, but Ford also required more mainstream models to achieve its ambitious sales targets. In 1998, Ford introduced the Jaguar S-Type and X-Type models, intended to compete with mid-market models such as the BMW 5 Series and the Mercedes-Benz E-Class. The company had high expectations for these new models, which were developed following a $700 million investment in design and production. Initially, the Jaguar S-Type received positive feedback and garnered numerous orders. However, its controversial exterior design and a perceived “less than premium” quality in the cabin led to declining sales for the S-Type.

Ford set an optimistic sales target of 100,000 units per year for the X-Type, but this goal was never achieved. As the most affordable car in the Jaguar line-up, the X-Type sold a total of 350,000 units (cumulative) over its eight-year production span (Source–drive.com). Jaguars traditionally feature rear-wheel drive, providing power to the rear wheels and emphasizing sporty characteristics. However, Ford broke from this tradition with the X-Type, which shared its production platform with the front-wheel-drive mass-market Ford Mondeo. Additionally, Ford incorporated components (e.g., Switchgears) from its mass-market cars into the X-Type, ultimately tarnishing Jaguar’s image.

Ian Callum, the designer tasked with infusing contemporary styling into Jaguar, remarked that the X-Type was not the right car for its intended audience (source-autoblog). He further stated that there were senior managers within both Ford and Jaguar who failed to understand the values of the British brand. Eventually, the X-Type was discontinued in North America and Europe, and in 2007, Jaguar’s sales dropped by a fifth. Ford’s series of mistakes severely damaged Jaguar’s luxury image. In 2008, Tata Motors acquired the Jaguar and Land Rover brands from Ford for a mere $2.3 billion, significantly less than the $5.2 billion Ford had originally paid for them in the 1990s (Source–New York Times).

These strategic failures cannot be solely attributed to management errors. They stem from an inability to comprehend the distinctions between the business strategies of luxury and premium brands. Specifically, a luxury brand cannot maintain its luxurious status if it fails to preserve its exclusivity and accessibility to a select elite.

Understanding the positioning of a brand – Luxury vs Premium

Luxury brands are based around heritage, prestige, and uniqueness. Luxury consumers aren’t interested in more features or in giving better value for money. ‘More features’ and ‘value for money’ are features of premium brands.

As discussed above, luxury, premium and fashion are three different ways to communicate a brand’s values to the customer base.

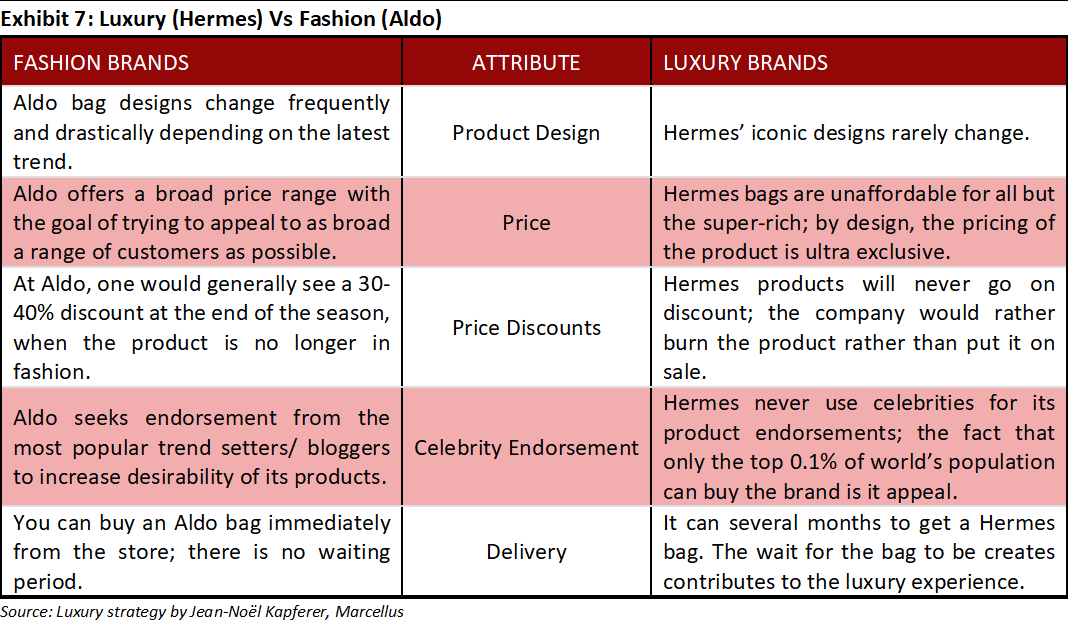

Right up to the turn of the 19th century, fashion belonged to the luxury world; only the privileged UHNW elite could afford the luxury of not having to wear their clothes until they had worn out. As affluence grew in the Western economies, thanks to the industrial revolution, in the 20th century the masses could afford to indulge in buying clothes without being driven by necessity to do so. At this point, ‘fashion’ diverged from ‘luxury’, and today the overlap between luxury and fashion is slight. A luxury product today is symbolic of a desire to belong to an elite class of consumer. For example, a Hermes handbag is a luxury product whereas a handbag from Aldo can be considered to be ‘fashion’

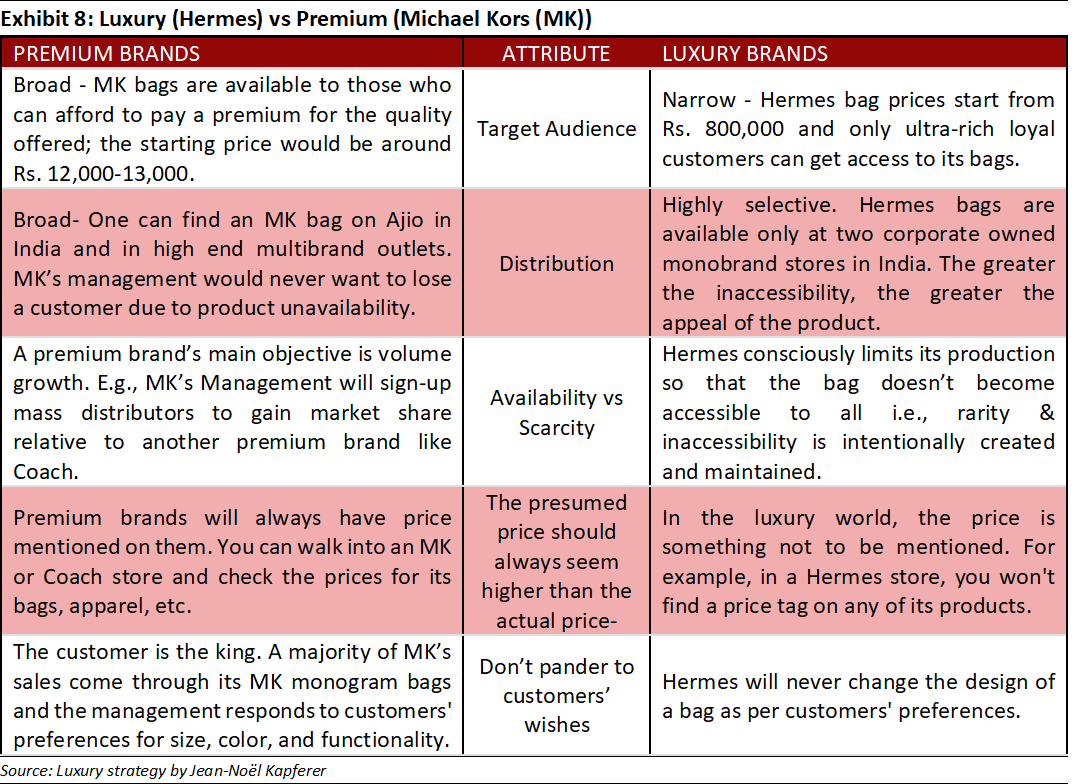

For luxury consumers, the status associated with a particular brand outweighs the function of the product itself. It is important for the product to make a luxury customer look & feel elite. Premium consumers, on the other hand, seek a quality brand they can rely upon to function well. A luxury brand is related to scarcity, quality, and storytelling and a premium brand is an expensive variant of commodities in general: i.e., pay more, get more. We can understand the subtle differences between Luxury and Premium brands based on two broad areas: 1) product strategy; and 2) the behaviour of the Management team. Let’s try to understand each attribute by using Michael Kors (MK) as an example of a premium brand, and Hermes as an example of a luxury brand.

Investment implications – Resilience of ‘Luxury’ compared to ‘Premium’ and ‘Fast Fashion’.

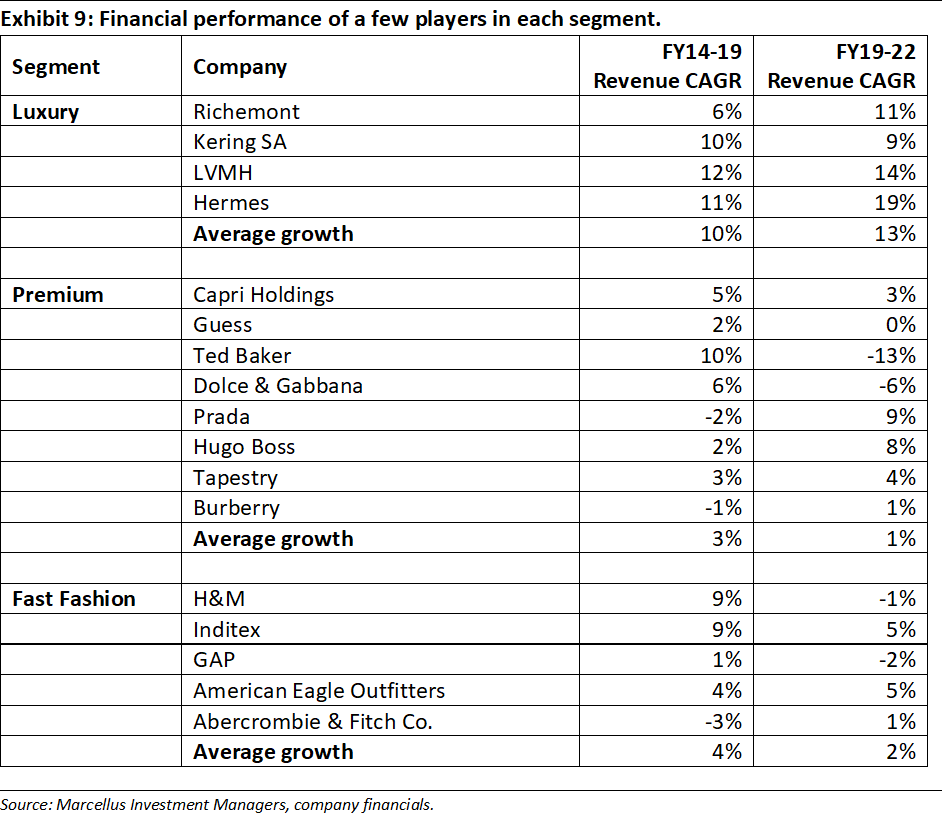

Initially when the pandemic started, it had a significant impact on luxury companies as store closures and restricted international travel affected their sales. However, the luxury industry experienced strong growth following the pandemic. Sales recovered from $250 billion in FY20 to $322 billion in FY21 (Source-Forbes). Approximately 20-30% of luxury purchases were made by consumers outside their home countries. Despite these challenges, luxury companies experienced only a 21% decrease in revenue in FY20 before recovering significantly in 2021 and 2022. Exhibit 9 demonstrates that luxury companies achieved a revenue growth of 13% CAGR from 2019 to 2022. In contrast, most premium product-oriented companies experienced a 1% CAGR, while fashion-oriented companies saw a modest 2% CAGR over the same period.

The growth in the luxury industry can be attributed to the increasing number of USD millionaires worldwide. From 2010 to 2021, the number of millionaires grew at a 9% CAGR, representing 48% of global wealth in FY21 compared to 36% in FY10. The net worth of millionaires exhibited an 11% CAGR, surpassing the 6% CAGR of the $100,000-$1 million wealth category. (Source: Credit Suisse Global Wealth Data)

An analysis of the luxury industry reveals compelling trends and growth drivers that pave the way for its future success-

- The Luxury personal goods industry is expected to grow from $353 billion in 2022 to $530 billion by 2030, representing a CAGR of 6% (source: Bain and Company). This growth is supported by demographic tailwinds and shifting consumer preferences.

- The number of millionaires worldwide is projected to increase at a CAGR of 6% over the next 5 years, reaching approximately 87.5 million, compared to 62.5 million millionaires in FY21 (source: Credit Suisse- Global Wealth Report 2022).

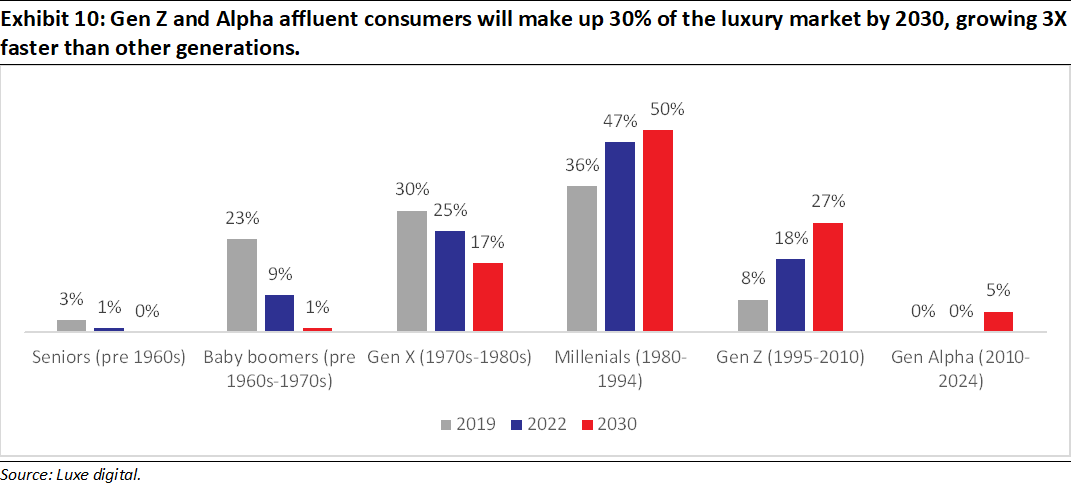

The growth of the global luxury market in 2022 was driven primarily by Millennials and Gen Z (categorization basis year of birth given in exhibit below). This generational shift is expected to create new revenue growth driver, with Gen Z and Gen Alpha’s luxury spending anticipated to grow three times faster than other generations (source: Bain and Company).

An example of a Luxury company from Marcellus’ GCP portfolio – Hermes International

Overview: Hermes is a French luxury goods manufacturer. The 186-year-old firm is consistently ranked as one of the world’s most valuable luxury brands. Hermès products are available worldwide through a network of 306 exclusive company owned stores. Hermès watches, perfumes and tableware are also sold through networks of specialised stores. Around 40% of the firm’s revenue comes from selling leather goods (mainly bags), followed by ready-to-wear apparels and accessories (27% of revenues), and silk and textiles (12% of revenues) (source– Hermes 2022 Annual report).

Drivers of competitive advantages for Hermes

Hermes as a brand is known for its heritage, craftsmanship and exclusivity in the ultra-luxury leather and silk products. There are several drivers of Hermes’ competitive advantages, such as:

1) History and Heritage: One of the things that’s hardest to disrupt in a luxury brand like Hermes is the heritage of almost 200 years which creates a huge aspirational brand recall. The company’s philosophy has always been to maintain scarcity and exclusivity. Customers cannot expect to walk into a store and walk out with a Birkin bag. Instead, one has to place an order and wait for a few months before it is ready. Hermes’ brand management approach – which includes requiring a customer to join the waiting queue for buying a Birkin bag or a Kelly bag, seeking an appointment on the day of purchase and celebration of the purchase at a flagship store with champagne, tea, cakes, etc – maintains this aspirational quotient of their brand.

2) Craftsmanship, raw material procurement and the production process: Hermes’ brand philosophy is deeply entrenched around attributes of “quality” and “refinement”. It is for these principles that the brand has always shunned mass production, manufacturing lines and outsourcing. According to Hermès, each and every product coming out under the brand’s name should reflect the hard work put into it by the artisan. Even today, Creative Director Pierre-Alexis Dumas signs off on every single Hermès product before it leaves the workshop, showing the company’s unwavering commitment to the highest quality. A handmade leather product at Hermes is the work of a single artisan. There is a mandatory two-year training for a craftsman before he or she can start working on putting together any leather product in the Hermès portfolio. Even though this slows down the production time, it creates the luxury attribute of supreme quality and exclusivity. The best quality leather would be procured for these products – e.g., a contiguous piece of leather, not stitched together from different panels. 48% of Hermes’ employees work in the production process. Hermes’ subcontractors and suppliers are mainly long-term partners. As such, for direct purchasing (production purchases), the average length of trading relationships with the Hermès Group’s top 50 largest direct suppliers in 2022 was 20 years. Of these 50 suppliers, 93% of purchases are made in Europe, with 56% in France. (source- Hermes 2022 Annual report)

3) Employee incentives: Hermès has set itself apart in recent years by the implementation of employee shareholding plans, and notably free share plans in 2007, 2010, 2012, 2016 and 2019. Under this collective plan, each eligible employee worldwide (i.e., more than 13,000 employees in various countries) thus received rights to free shares, i.e., a total of 500,544 shares. On 31st December 2020, employee shareholding represented 1.1% of the share capital, i.e., over one billion euros worth of shares are held by employees. At the end of 2020, nearly 80% of its employees held rights that were vesting and accordingly, continue to be involved in the Hermès Group’s governance and operations over the long-term, in a spirit of mutual trust with the House (source-Hermes 2020 Annual report).

Hermès regularly goes back to its roots when it needs to find inspiration for creating and launching new products. There is a sense of entrepreneurship built in store managers – they are responsible for their own store collections and are offered the freedom of purchase to meet specific needs of their customers. Hermès has offered repair services since Thierry Hermès established the company in 1837, the approach is to create timeless durable, well-crafted goods that are designed to be passed from one generation to the next.

Growth strategy: Hermes caps volume growth in its leather goods production at 6-7% annually, preferring to have long waiting lists for its products rather than accelerate production. Executive Chairman, Dumas said the group had no plans to change this strategy of keeping volume growth low: “It takes 15 hours for a Hermes bag. Even if there’s a lot of demand, I’m not going to start doing them in 13 hours to raise production,” (Source: Reuters).

Over the last 10 years, Hermes’ revenue has grown at a CAGR of 13%, FCFF has grown at a CAGR of 21% with pre-tax ROCE’s consistently hovering around 40% (capital reinvestment rate of 20%). (Source– Hermes 2022 Annual report). Over the last 1, 3, 5 and 10 years, this company has compounded shareholder returns at 66%, 43%, 30%, 23% respectively.