OVERVIEW

Consumption patterns show that India’s urban middle class is suffering. We believe that there are 3 reasons for this: (a) In offices & factories, technology is replacing humans in jobs entailing routine work; (b) The Indian economy is in the early stages of a cyclical economic downturn; and (c) Household balance sheets in India appear to be in their worst shape in half a century. Whilst the Indian economy should emerge from its cyclical downturn in a few quarters, the potency of the other two factors could likely make things worse before they get better.

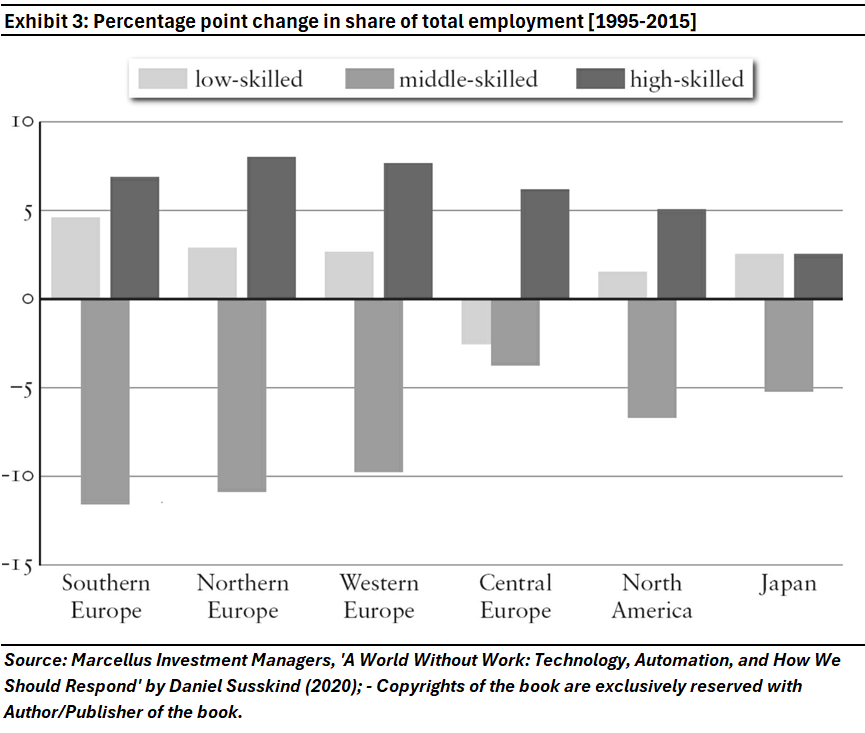

“The traditionally plump midriffs of many economies, which have provided middle-class people with well-paid jobs in the past, are disappearing. In many countries, as a share of overall employment there are now more high-paid professionals and managers – as well as more low-paid care workers and cleaners, teaching and healthcare assistants, caretakers and gardeners, waiters and hairdressers. But there are fewer middling-pay secretaries and administrative clerks, production workers and salespeople.” – Daniel Susskind in his book ‘A World Without Work: Technology, Automation, and How We Should Respond’ (2020)

The rise of the middle class is a well-documented phenomenon

As any free-market economy develops, it brings in its wake a slew of social & economic changes. One of the key changes that typically take place is the rise of a fast-growing middle class. This middle class consists of those who, using their enterprise and/or intellect, rise from the trenches of low-income cohorts.

In the United States, in the period after the second World War, the middle class quickly became a key demographic – socially, politically, and economically. The impact of this ascent was profound. Daniel Susskind has said in Finance and Development Magazine (IMF) in September 2024, “As the 20th century unfolded, the demands of war faded. Yet the pursuit of growth stubbornly persisted. For growth, it turned out, was also associated with almost every measure of human flourishing. Growth freed billions from the struggle for subsistence, with extreme poverty dropping from 8 in 10 people in 1820 to just 1 in 10 today. It made the average human life longer and healthier—turning obesity, rather than famine, into the rich world’s main problem. And it dragged humankind out of ignorance and superstition: 9 in 10 were illiterate in 1820, but 9 in 10 are literate today.”

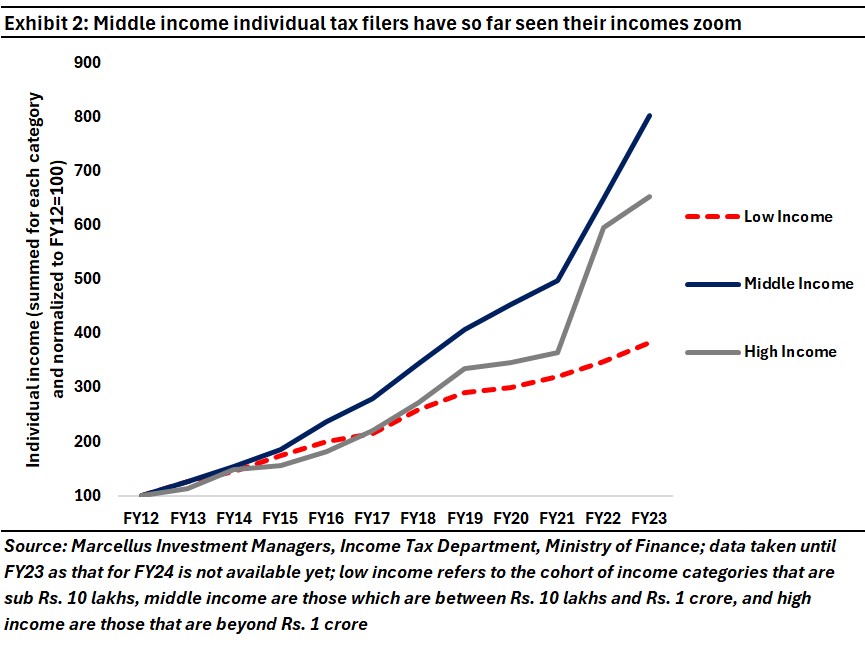

India too has seen a large middle class emerge over the past 40 years. In fact, if we were to look at the Income Tax Department’s data for individual taxpayers, individuals earning between Rs. 10 lakhs and Rs. 1 crore have seen their incomes grow at roughly 20% p.a. in the decade that went by, whereas those earning less than Rs. 10 lakhs of annual income have seen an annual growth of just 12% (see chart below).

Things go awry for the Indian middle class

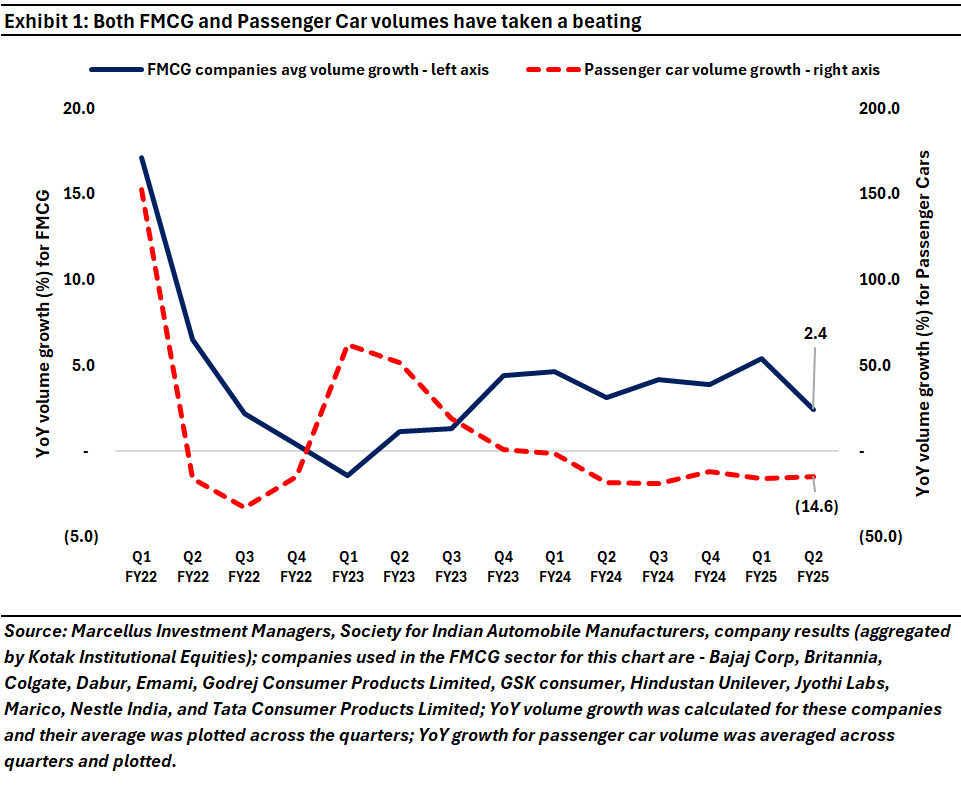

Recently, however, there has been a lot of chatter around the ‘slowing down’ of consumption of items and services typically associated with the urban middle class. Nestle India’s MD, Mr. Suresh Narayanan, said after the firm’s Q2 FY25 results that “there used to be a middle segment which used to be the segment most of us FMCG companies used to operate in, which is the middle class of the country. That seems to be shrinking. And there is a completely, purely price-quality-be-damned-led segment, which also seems to be doing reasonably well.” [source: Financial Express]

Mr. RC Bhargava, chairperson of Maruti Suzuki, explained in an interview that “In FY18-19, 82% of the cars that were sold were below ₹10 lakh. Now that segment is not growing anymore. It is declining actually. So you can judge for yourself if that large segment does not grow and actually declines how much can the other segment grow and make up for this 80% segment.” [source: CNBC TV18]

Mr. Narayanan’s, Mr. Bhargava and others’ concerns are well-founded as incrementally data on consumption of items that are typically found in a middle-class Indian’s basket has slowed or even started degrowing (see exhibit 1).

So why are the wheels coming off from the Indian “middle class” story?

1. Technology is replacing human labour in jobs that are routine and repetitive

As we try to understand this phenomenon, we find that over the past 40 years something similar has taken place in the developed economies. As Daniel Susskind explains in his 2020 book ‘A World Without Work: Technology, Automation, and How We Should Respond’ –

“Starting in the 1980s, new technologies appeared to help both low-skilled and high-skilled workers at the same time – but workers with middling skills did not appear to benefit at all. In many economies, if you took all the occupations and arranged them in a long line from the lowest-skilled to the highest-skilled, over the last few decades you would have often seen the pay and the share of jobs (as a proportion of total employment) grow for those at either end of the line, but wither for those near the middle. We can clearly see this trend [in the exhibit below]. This phenomenon is known as ‘polarization’ or ‘hollowing out’.” [square brackets are ours].

In India, too, we now see clerical, secretarial and other routine work in offices & factories being automated. So far, AI is not required to automate these jobs e.g., you don’t need AI to replace a teller in a bank branch with an ATM. However, as AI gradually becomes sophisticated (as generative AI makes the bots cleverer), it seems reasonably certain that more white-collar jobs will be lost. As Rishad Premji, Chairman of Wipro, puts it, “I think that two-three… elements that people think which are very important is the disruption of the technology process… the reality is, there are going to be some jobs that will disappear…“I think the good part is the opportunity to disrupt virtually every aspect of our life with the productivity that AI can bring is going to be incredibly powerful.” [source: Money Control]

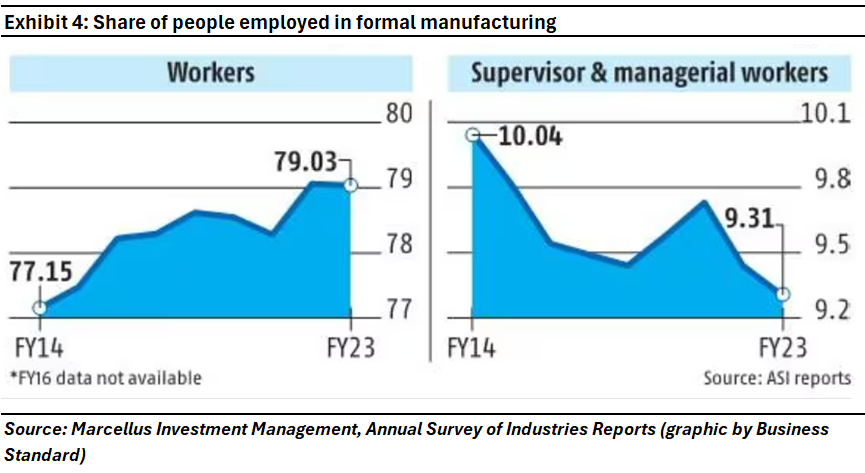

In fact, if we were to look at the recently published data in the Annual Survey of Industries, the number of supervisors employed in manufacturing units (as a % of all employed) in India has gone down significantly (see exhibit below).

PC Mohanan, former acting chairman of the National Statistical Commission (NSC), has said that “The decline in administrative job roles has been observed for quite some time now. Besides, the increasing trend of contractualisation and outsourcing by producers as a measure to cut input costs implies that many managerial and supervisory roles no longer exist. While workers are needed to produce and operate machinery, supervisors are no longer required for them.” [source: Business Standard]

2. A cyclical downturn, although less worrying, is another factor weighing on middle-class consumption

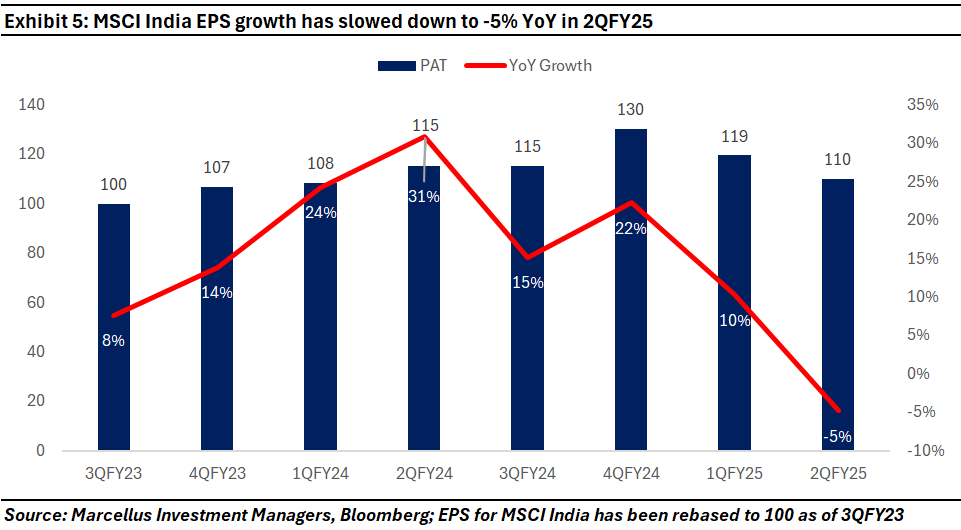

Leaving aside AI, the Indian economy is undergoing a cyclical downturn after three years of bumper economic growth (FY22, 23 & 24) post-Covid. The force of this cyclical downturn can be seen in the potency of the slump in corporate earnings – see exhibit below which seeks to capture what appears to be the steepest slump in earnings growth in 20 years (leaving aside exigencies like the Global Financial Crisis and covid).

This sort of downturn is typical for any free-market and democratic economy, and given the right course correction from monetary and fiscal policy actions, the pain from the downturn is likely to be short-lived.

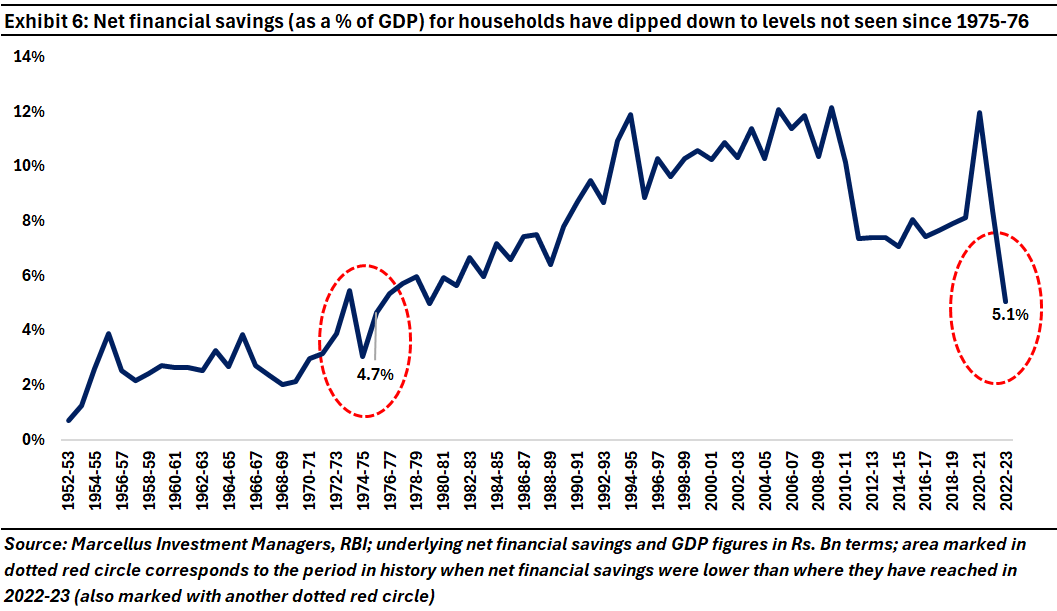

3. Net household savings are at the lowest level seen in the last 50 years

After four years of relentless growth in loans outstanding, Indian households’ balance sheets are in their worst shape in 50 years. As per RBI data, net household financial savings as a % of GDP are at their lowest since 1976. A key point of distinction here, though, is that gross household saving (as a % of GDP) hasn’t fallen that much and is steady at 10-11% (barring the covid year when it shot up to 16%). It is the rise in household liabilities (mostly unsecured debt – read more on the subject in our previous note dated October 2023, Midnight Approaches for India’s Retail Lending Boom) that has caused the net household savings figure to dip so precipitously in the last couple of years.

Complementary effect of humans with technology needs to be understood

The second factor mentioned above (economic downturn) is cyclical. However, the first (technology replacing human labour) & third (low net household savings) factors are going to be trickier to resolve. Middle class consumption, therefore, looks likely to stay muted for a few more quarters before things change for the better.

All of that being said, there are a few reasons for believing that there is light at the end of the tunnel. Whilst the substitution of human beings with tech is called the “substitution effect” (that’s what Rishad Premji is referring to), technology also has a “complementary effect” i.e., it helps people earn more, spend more and thus create new jobs. In our subsequent blogs we will delve deeper into this dynamic.

Nandita Rajhansa and Saurabh Mukherjea work for Marcellus Investment Managers (www.marcellus.in). Nestle and Tata Consumer Products Limited are part of Marcellus’ portfolios. Nandita and Saurabh may be invested in these companies and their immediate relatives may also have stakes in the described securities. The stock mentioned is for illustrative purpose and is not recommendatory.

the above material is neither investment research, nor investment advice. Marcellus does not seek payment for or business from this material/email in any shape or form. Marcellus Investment Managers Private Limited (“Marcellus”) is regulated by the Securities and Exchange Board of India (“SEBI”) as a provider of Portfolio Management Services. Marcellus is also a US Securities & Exchange Commission (“US SEC”) registered Investment Advisor. No content of this publication including the performance related information is verified by SEBI or US SEC. If any recipient or reader of this material is based outside India and USA, please note that Marcellus may not be regulated in such jurisdiction and this material is not a solicitation to use Marcellus’s services. All recipients of this material must before dealing and or transacting in any of the products and services referred to in this material must make their own investigation, seek appropriate professional advice. This communication is confidential and privileged and is directed to and for the use of the addressee only. The recipient, if not the addressee, should not use this material if erroneously received, and access and use of this material in any manner by anyone other than the addressee is unauthorized. If you are not the intended recipient, please notify the sender by return email and immediately destroy all copies of this message and any attachments and delete it from your computer system, permanently. No liability whatsoever is assumed by Marcellus as a result of the recipient or any other person relying upon the opinion unless otherwise agreed in writing. The recipient acknowledges that Marcellus may be unable to exercise control or ensure or guarantee the integrity of the text of the material/email message and the text is not warranted as to its completeness and accuracy. The material, names and branding of the investment style do not provide any impression or a claim that these products/strategies achieve the respective objectives. Further, past performance is not indicative of future results. Marcellus and/or its associates, the authors of this material (including their relatives) may have financial interest by way of investments in the companies covered in this material. Marcellus does not receive compensation from the companies for their coverage in this material. Marcellus does not provide any market making service to any company covered in this material. In the past 12 months, Marcellus and its associates have never i) managed or co-managed any public offering of securities; ii) have not offered investment banking or merchant banking or brokerage services; or iii) have received any compensation or other benefits from the company or third party in connection with this coverage. Authors of this material have never served the companies in a capacity of a director, officer, or an employee. This material may contain confidential or proprietary information and user shall take prior written consent from Marcellus before any reproduction in any form.