OVERVIEW

For a decade or so now, it has been well understood that more women in India are increasingly getting educated (in terms of numbers) and doing it better (in terms of quality) than India’s men. Interestingly, new data shows that urban Indian women typically have more money in the bank than Indian men AND in India’s booming tech industry, women earn more than men. At Marcellus, we are tilting our portfolios towards companies that focus on India’s women. We believe that the rise of Indian women’s wealth and spending will be one of the defining investment themes for many years to come.

“While education has not changed the male engineer’s mind, education has empowered this girl to walk out of a marriage and earn her own livelihood and to bring up her daughter. Such economic independence would not have been possible without education. I saw this again and again as I travelled through different parts of the country. It was heartening to see in Census 2011 that for the first time the number of additional literate women in the last ten years exceeded the number of additional literate men. This convergence of literacy rates over the next ten years will be a big driver of women’s economic independence and empowerment in my view.” – Anirudha Dutta, author of ‘Half a Billion Rising: The Emergence of Indian Women’ (2015) [source: https://www.linkedin.com/

Surging education levels has been a gamechanger for India’s women

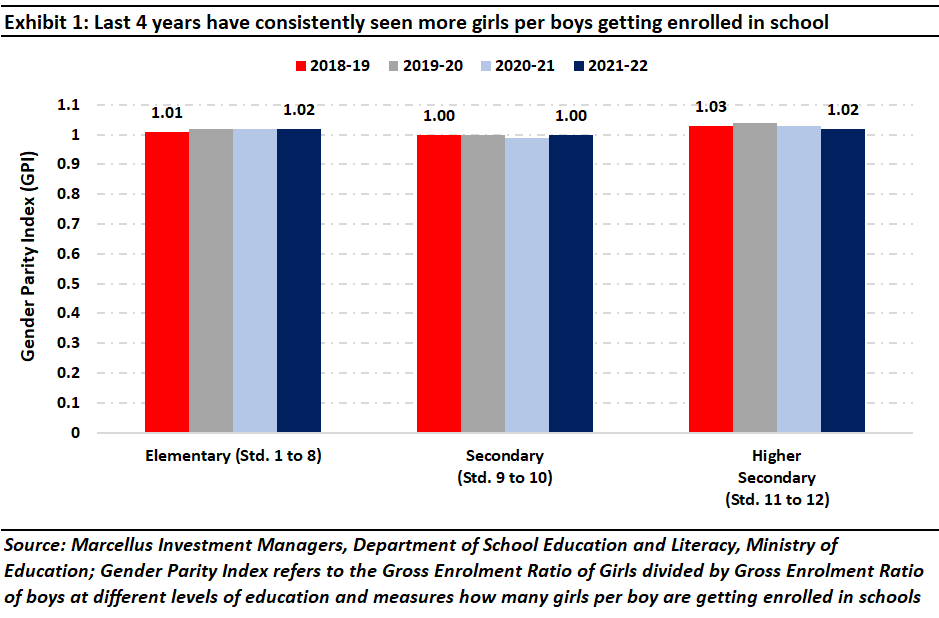

When a decade ago Anirudha Dutta was researching his prescient book on the rise of Indian women, the women in question were just nudging ahead of India’s men in terms of the Gender Parity Index (GPI), which measures how many girls per boy are getting enrolled in school, across all levels. Over the last four years, across all levels of the Indian educational system, the GPI has been greater than 1 (see exhibit below) indicating that more girls than boys are getting enrolled in schools at all levels of education!

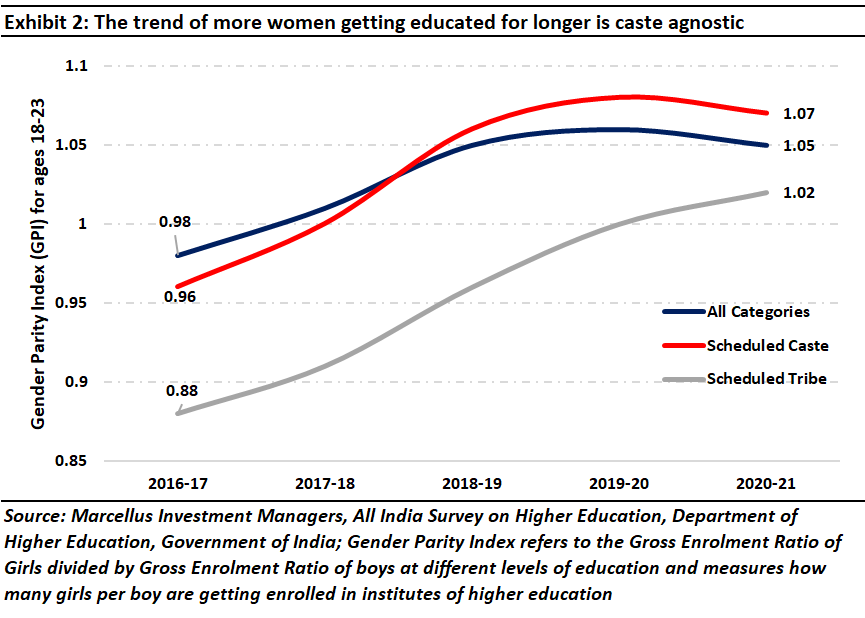

In fact, if we go one step further and look at the GPI for higher education (i.e., for the age group 18-23 years), not only is the GPI greater than 1 across all social categories (see exhibit below), but the improvement has also been most rapid for Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes indicating that women in the most disadvantaged sections of Indian society are powering ahead the fastest.

Not only are more Indian women getting educated, but they are also getting educated more rapidly than their male counterparts. India’s female literacy rate in 2011 was 64.6% as compared to the male literacy rate of 80.6%. However, between 1961 to 2011, the female literacy in India has grown 3x as fast as male literacy (~3% p.a. vis-à-vis ~1%).

However, the ascendancy of Indian women in education is even more comprehensive than what the enrolment numbers suggest – not only are more women getting educated than men, but the women are also BETTER educated than men. We know this because, as recently as May 2023, the pass percentage of girls was 6% points higher than that of boys in class 12 examinations of the Central Board of Secondary Education (CBSE). This was also the case back in 2010, when female pass percentage in class 12 examination was north of 80% as opposed to male pass percentage of ~73%!

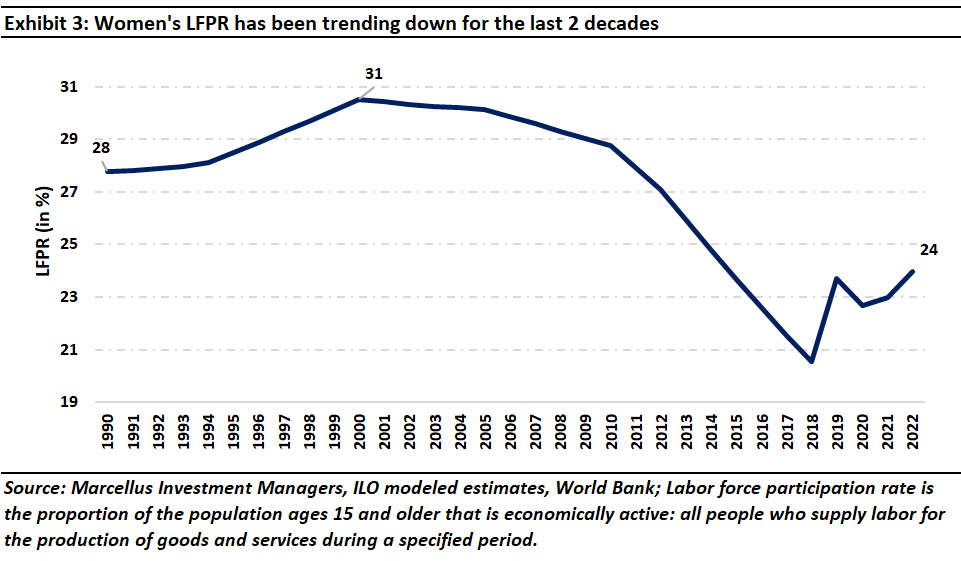

Interestingly though, despite the uptrend in educational attainment of women in the country, their Labour Force Participation Rate (LFPR) has been trending down since 2000 when it peaked at ~31% (see exhibit below). And whilst the rate in the last 3-4 years has slightly inched up, it is way below even the level in 1990.

Because of this seemingly worrying trend visible in the data, there is naturally a lot of concern and noise around both the employability and income of women in the country. Are these concerns rightfully justified and is the situation of Indian women really worse than what it was 30+ years ago?

We believe the answer to both these questions is an emphatic “no”. Indian women today are in a much better position, socially and financially, than they ever were. There are primarily three reasons why we believe so.

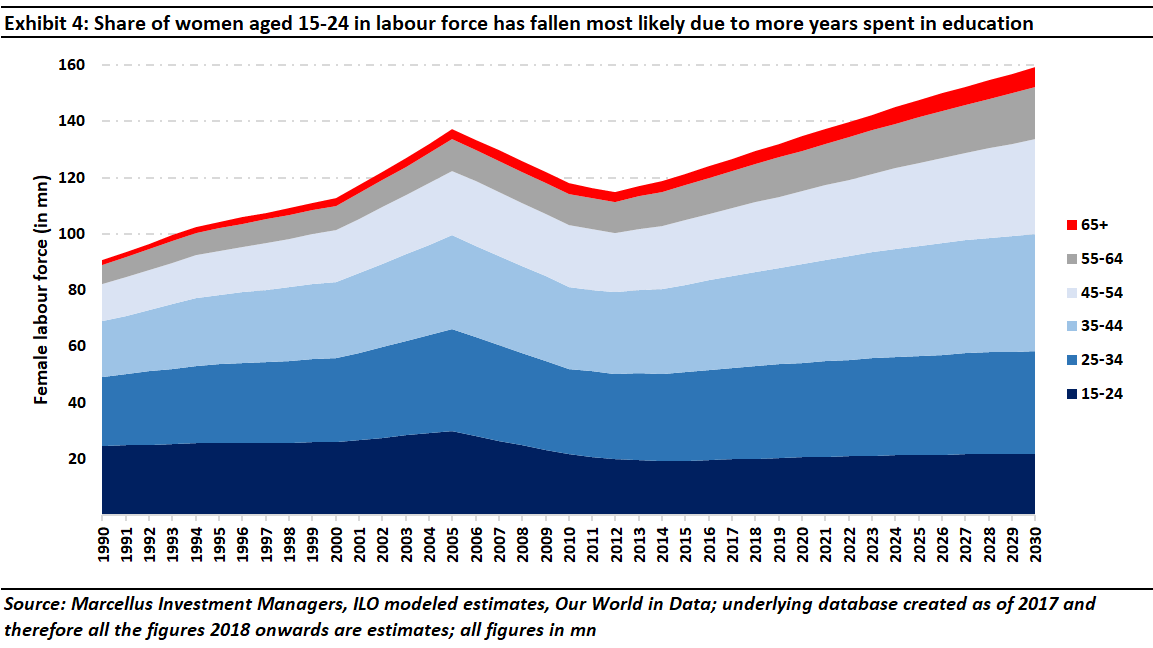

Education is a major driver of delayed workforce entry

When someone stays longer in the education system, their entry into the workforce will be later (than what it would have been had they not studied for longer). As we had pointed out in our 9th November 2022 note Educated, Employed, and Empowered: The Rise of Indian Women, “if we look at the LFPR data but with a different lens, namely age-wise stratification, a completely new picture emerges – whilst the LFPR for women in the age bracket 15-24 has gone down substantially since 2010, the LFPR for 25-35 years has remained fairly stable and remarkably, the LFPR for 35+ age bracket has actually gone up (see exhibit below).”

If you combine this with the fact that a majority of India’s demography in the past decade was in the 15-24 bracket (source: Future of Global Wealth Management report by BCG and Kotak Wealth Management, 2020) implies that as more girls were getting educated, it impacted the LFPR adversely. However, such an impact is optical because as this cohort starts entering the workforce, the LFPR will improve. Ironically, if you believe in this line of thought, a more decisive improvement in LFPR will only happen when India starts to age (because then, in proportional terms, fewer Indian women will be entering higher education and a greater proportion will be in the workforce).

The wage gap between women and men has narrowed

Whilst gender parity on wages is an ongoing battle the world over, considerable progress has been made in the last 30 odd years. According to International Labor Organization (ILO) and National Statistical Survey Office (NSSO), India’s women on an average earned 48% less than their male counterparts in 1993-94. In contrast, in 2018-19, this gap had reduced to 28%. In fact, if we were to refer to the Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) for 2021-22, the share of urban women in regular wage/salaried employees exceeds that of urban men at 50.3% vis-à-vis 46.2% respectively. In contrast, the same cannot be said for rural women and men. Intuitively, this makes sense as more educated and skilled women become, the more intellectually inclined jobs will be lapped up by them. Because urban centres provide such employment opportunities more than rural areas, logically that’s where women are more likely to excel professionally and that is precisely what is happening.

Taking the argument in the preceding para to its logical conclusion would suggest that in the most hi-tech part of the Indian economy, women should be earning more than men. That’s exactly what surveys of India’s tech sector show – women in technology earn on an average 7% more than men.

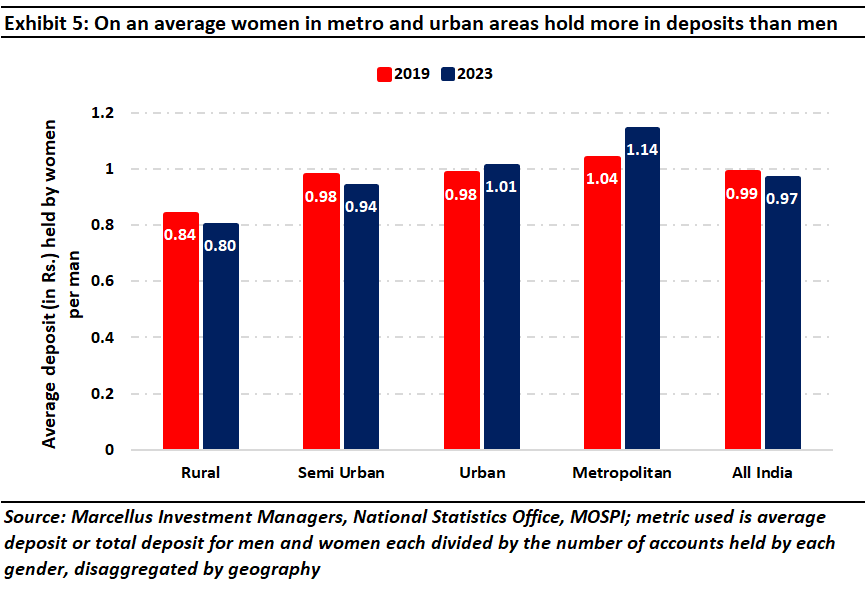

In urban India, women typically have more money in their bank accounts than men

The flow of money into bank accounts is a function of wages. At a pan-India level, men on an average hold INR ~90K in their bank accounts, whereas women hold less than half that amount.

However, the numbers change dramatically if we look at the bank deposits data for urban India (where the role of physical strength in earning money is lower than it is in rural India). In ‘urban’ areas (defined by the RBI as centres with population above 1 lakh but less than 10 lakhs), women’s deposit balances have on average grown by 3% from 2019 to 2023 to exceed 1 (meaning higher deposit figure in women’s account than in men’s) in 2023 (see exhibit below). More stunningly, in ‘metropolitan’ areas (defined by the RBI as areas with population greater than 10 lakh), women’s average deposit ticket size has grown by 10% from 2019 to 2023, way above 1, and hence larger than those of men.

In the years to come, as the Indian economy moves increasingly from being dominated by industries investing in tangible assets to the ones investing in intangible assets (see our note dated 7th February 2023, Exit Traditional Capitalism, Enter ‘Capitalism Without Capital’), the kind of jobs that incrementally get generated will require greater intellectual muscle than physical strength. With better skilled women entering the workforce, where the demand of skilled labour gets satisfied by this cohort, there is a strong reason to believe that wealth and income will swing in favour of urban India’s women even more decisively.

Whilst the above chart suggests that only in recent years, urban Indian women’s bank accounts have become bigger than their male counterparts, we believe that there is a high probability that this trend goes back at least a decade. However, until the rise of Jan Dhan and then UPI, many urban women did not have bank accounts of their own which meant that their money was sitting either at home or in their husband’s bank account. Over the last four years with UPI having become the preferred mode of payment in urban India, Indian women’s earning power is showing up not just in their bank accounts but also in how they invest. As noted in our 9th November 2022 blog, Educated, Employed, and Empowered: The Rise of Indian Women, “With the growing ease of access to smartphones and thanks to low-cost broadband, Indian women are accessing the financial system not only through bank accounts and traditional instruments like Fixed Deposits (FDs) but also experimenting with new age investment avenues like cryptocurrency. Shaili Chopra writes in her book ‘Sisterhood Economy’ (2017), “This is a story of a woman who wanted to dabble in cryptocurrency in the words of Kavita Gupta of Delta Blockchain Fund… A student from a village in Punjab studying engineering and working as a receptionist had crypto money. She invested Rs. 100 every day in crypto from the salary that she earned as a receptionist. Later she earned so much money through crypto that she was able to pay her education loan. So as far as digitalization of financial services are concerned, options for investments and savings have dimensionally increased and become easier and young girls are willingly experimenting.””

Investment Implications

As India’s women earn more and get wealthier, relative to their male counterparts and relative to their own past, it is but inevitable that we will see the rise of women-centric consumption. Businesses that cater to this new source of surging demand therefore stand to do well. In Marcellus we are tilting our portfolios proactively to this new source of wealth in India. Here are four examples from our various portfolios:

Titan:Capitalizing on the theme of rising women-centric consumption like no one else, Titan is by far India’s most profitable jeweller (Titan generated a ROCE of 40% in FY23 and Tanishq plus Caratlane account for ~95% of Titan’s profits). In fact, according to Titan Jewelry’s CEO, Mr. Ajoy Chawla, they are planning to expand Mia’s store count from 125 to up to 200 (Mia is Titan’s light and everyday wear jewelry brand). Titan, under its jewelry segment, offers four sub-brands – Mia, Caratlane, Tanishq, and Zoya – each catering to a different class of women with diverse set of tastes and purchasing power. Four years ago, Titan launched Taneira, a rapidly growing chain of ~50 stores selling expensive sarees priced at Rs 10-30k.

Nestle:Baby food contributes to be ~20-25% of Nestle India’s overall business and happens to be the most profitable category for Nestle India due to strong barriers to entry in this market. As more women are going to work, sales of baby food are picking up due to the convenience factor attached to it. In September 2022, Nestle brought its Gerber food brand to India. As the advertising campaign for Gerber shows, busy mothers who want to give their kids ready-made nutritious meals are the target market for this premium product – see https://brandequity.

Trent: Westside was started as a woman-centric apparel retailer 25 years ago when women’s apparel was a smaller portion (<30%) of the overall apparel market. Additionally, women’s apparel is the most challenging category to cater to, given the high variety and fashion element that needs to be constantly monitored. This requirement, in a way, also offers the chance for a retailer to build a sustainable competitive advantage vis-à-vis other retailers who haven’t been able to crack this need to manage lots of SKUs churning almost weekly. As India’s women have become prosperous, Westside has flourished. Today Westside has ~220 stores with greater than two thirds of their revenue coming from women’s apparel. In the last few years, Trent has launched new women-centric formats such as Misbu for cosmetics, Samoh for premium occasion wear, and Utsa for women’s ethnic wear.

Rainbow Hospitals:Hyderabad based Rainbow hospitals has risen in the last 20 years to become one of the largest pediatric and maternity focused hospitals in southern India. Until about two decades ago, there were no mother-child hospitals or birthing-only specialty hospitals; mother-child care was catered to by sub-units of multi-specialty hospitals or nursing homes. People lived in joint families and grandmothers’ knowledge influenced maternal care; therefore, multiple visits to the gynae or pediatricians were not needed. With the rise of the double income nuclear family in booming cities like Hyderabad, Bangalore, and Gurgaon and with rise of delayed pregnancies (which are more complex) as women pursued their careers, there was a need for focused mother-child hospitals. Rainbow has filled this void, starting with Hyderabad and over time extending to other areas in southern India. In addition, with the rise in income levels, hospitals like Rainbow have fulfilled the customer need to make birthing a 5-star hotel type experience. Today Rainbow has ~1600 operational beds spread across 17 hospitals in Hyderabad, Bangalore, Delhi, Andhra Pradesh, & Tamil Nadu. The firm’s bed count is expected to increase by 50+% in the next 3 years as it expands its footprint further in sync with the surging income levels of India’s women.

Nandita Rajhansa and Saurabh Mukherjea work for Marcellus Investment Managers (www.marcellus.in). Amongst the companies mentioned in this note, Titan, Nestle, Trent, and Rainbow are part of Marcellus’ portfolios. Nandita and Saurabh may be invested in these companies and their immediate relatives may also have stakes in the described securities.

If you want to read our other published material, please visit https://marcellus.in/blog/

Note: the above material is neither investment research, nor investment advice. Marcellus does not seek payment for or business from this material/email in any shape or form. Marcellus Investment Managers Private Limited (“Marcellus”) is regulated by the Securities and Exchange Board of India (“SEBI”) as a provider of Portfolio Management Services. Marcellus is also a US Securities & Exchange Commission (“US SEC”) registered Investment Advisor. No content of this publication including the performance related information is verified by SEBI or US SEC. If any recipient or reader of this material is based outside India and USA, please note that Marcellus may not be regulated in such jurisdiction and this material is not a solicitation to use Marcellus’s services. This communication is confidential and privileged and is directed to and for the use of the addressee only. The recipient, if not the addressee, should not use this material if erroneously received, and access and use of this material in any manner by anyone other than the addressee is unauthorized. If you are not the intended recipient, please notify the sender by return email and immediately destroy all copies of this message and any attachments and delete it from your computer system, permanently. No liability whatsoever is assumed by Marcellus as a result of the recipient or any other person relying upon the opinion unless otherwise agreed in writing. The recipient acknowledges that Marcellus may be unable to exercise control or ensure or guarantee the integrity of the text of the material/email message and the text is not warranted as to its completeness and accuracy. The material, names and branding of the investment style do not provide any impression or a claim that these products/strategies achieve the respective objectives. Further, past performance is not indicative of future results. Marcellus and/or its associates, the authors of this material (including their relatives) may have financial interest by way of investments in the companies covered in this material. Marcellus does not receive compensation from the companies for their coverage in this material. Marcellus does not provide any market making service to any company covered in this material. In the past 12 months, Marcellus and its associates have never i) managed or co-managed any public offering of securities; ii) have not offered investment banking or merchant banking or brokerage services; or iii) have received any compensation or other benefits from the company or third party in connection with this coverage. Authors of this material have never served the companies in a capacity of a director, officer or an employee.

This material may contain confidential or proprietary information and user shall take prior written consent from Marcellus before any reproduction in any form.