OVERVIEW

In a year in which, over 80% of India’s latest crop of graduates failed to get jobs, we find that university education in India neither increases the probability of employment nor gives an uplift to earnings. These challenges are being exacerbated by the rise of AI & automation. Specifically, the skills necessary to thrive in the AI transition – social skills, creativity, empathy, emotional intelligence, relationship building, collaboration, cultural sensitivity, interpersonal skills – are NOT the skills that India’s university system is designed to impart.

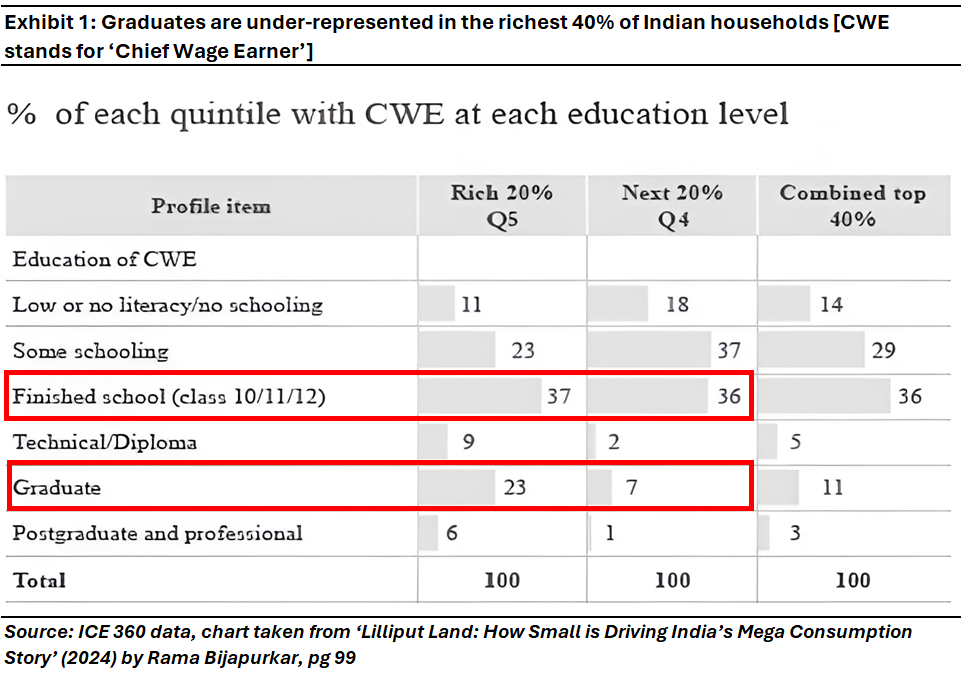

“India’s education system needs a huge upgrade and much has been written about this. While there is improvement in each successive generation, the overall picture continues to be bleak. A third of the chief wage earners of even the richest 20 per cent of Indian households have not even finished school while another 30 per cent have a college education and another 9 per cent have technical (polytechnic diploma type) education.” – Rama Bijapurkar, ‘Lilliput Land: How Small is Driving India’s Mega Consumption Story’ (p. 101)

The headlines around AI related job losses….

It is commonplace these days to open the newspaper and run into a headline or two which says that AI will cause widespread job losses across the world (e.g. this article from Accenture’s point of view that AI will impact 40% of all working hours as Large Language Models (LLMs) such as ChatGPT replace humans in ‘language tasks’: The jobs most likely to be lost and created because of AI | World Economic Forum ) or, more specifically, that AI will cause mass white collar unemployment in India (e.g. this article in India Today says 2 in 3 Indian engineers fear losing their job to AI: 67% of engineers fear job losses due to AI, 87% working to upskill – India Today).

These articles are not without substance. Our meetings over the past couple of months with India’s largest private sector employers in Banking & Financial Services suggest that they are planning to reduce headcount by around a third over the next couple of years by getting rid of call centres and cutting back on the use of coders (in their IT teams). Similarly, we are seeing in ATMs and bank branches, bots (alongside cameras & sensors) replacing human security guards (who cost Rs. 6 lakhs per annum and are, even at those modest salaries, twice as expensive as the bots). As R. Jagannathan wrote presciently in his book, ‘The Jobs Crisis in India’ (2018): “The bad news, however, is that millions of middle-class, middle-skill, good-quality, and stable jobs are now being chopped steadily. The once-secure jobs of clerks, cashiers, shop and office assistants, brokers, bookkeepers, administrative officers, and call-centre and retail sales personnel are either already gone, diminishing rapidly, or about to be reduced or eliminated altogether.”

However, even as the threat posed by AI to Indian jobs involving routine and/or repetitive tasks are real (see our blog dated 24th November 2024, Why is the Indian Middle-Class Suffering?), the bigger problem is widespread unemployment amongst newly minted university graduates in India. This unemployment challenge in turn is a manifestation of a more structural issue: the sub-standard education/skilling imparted by most Indian universities.

…Hide a more serious problem around graduate unemployment

Indians continue to study for entrance exams in ever greater numbers. For example, a record number of students – 1.2 million – sat the for IIT joint entrance exams in January 2024

(source: https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/delhi/jee-main-2024-record-123-lakh-registrations-maharashtra-leads-the-way/articleshow/105825059.cms#:~:text=State%2Dwise%2C%20Maharashtra%20(1.6,as%20compared%20with%202023%20exams.)

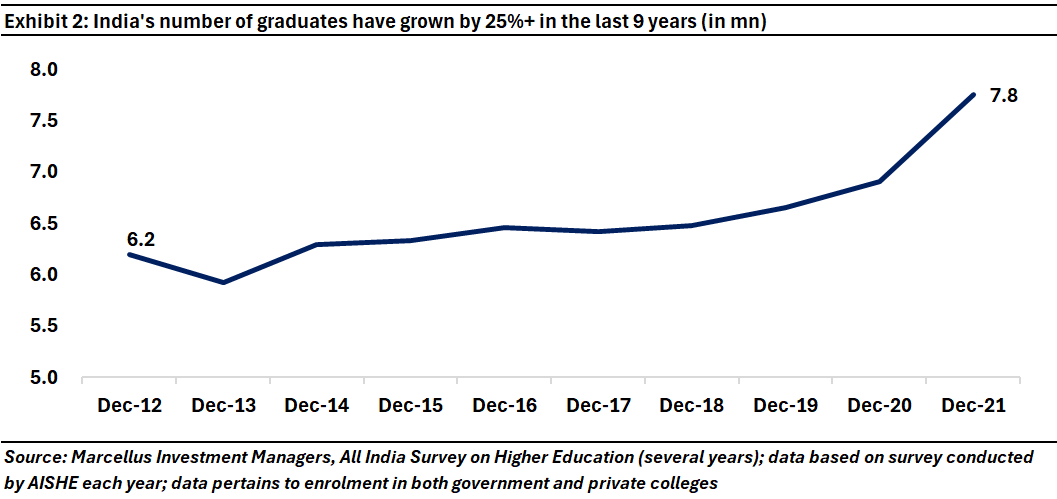

Unsurprisingly, therefore the Indian university system is producing graduates in ever larger numbers although bizarrely (and tellingly) there is no consensus on how many graduates India produces each year. Our reckoning, and relying on All India Survey on Higher Education (AISHE) which is the most exhaustive source of data for higher education in India, is that more than 8mn students graduate out of India’s university system each year (source: https://aishe.gov.in/aishe-final-report/) . The result is that the graduate pool in India is burgeoning rapidly as shown by the chart below.

The problem is that around 80% of these freshly minted graduates are not getting jobs. In fact, an article in the Times of India says that 90% of the latest batch of engineering graduates did not get jobs (hyperlink: Pursuing engineering once a fad, now a dilemma: Only 10 percent of 15 lakh graduates likely to land jobs this year – Times of India ).

Even more worryingly, even India’s most elite universities – the ones that millions of students spend years trying to enter – are being afflicted by the unemployment virus:

“The latest placement data from the Indian Institute of Technology (IIT) Bombay reveals a troubling trend: despite IIT Bombay’s achievement of its second-highest placement rate, overall employment figures and entry-level salaries have declined sharply. Around 75% of IIT Bombay students secured jobs this year, a drop from last year’s 78%, and the minimum wage has been cut from Rs. 6 lakh to Rs. 4 lakh. Nationwide, the situation is more severe, with over 8,000 out of 21,500 IIT graduates remaining unemployed, a significant increase from the previous year’s figures.”

(Source: https://apacnewsnetwork.com/2024/09/iits-witness-drop-in-placement-rate-and-minimum-pay-8000-iitians-remain-unemployed/#:~:text=Nationwide%2C%20the%20situation%20is%20more,the%20placement%20season%202023%2D24)

If we keep in mind that most university graduates get jobs paying Rs. 2 – 3 lakhs per annum (broadly the same as India’s per capita income) and even IIT graduates get only Rs. 4 lakhs per annum, it appears that high salaries are NOT the main driver of graduate unemployment in India.

Graduation hurts one’s chances of employment AND depresses earnings

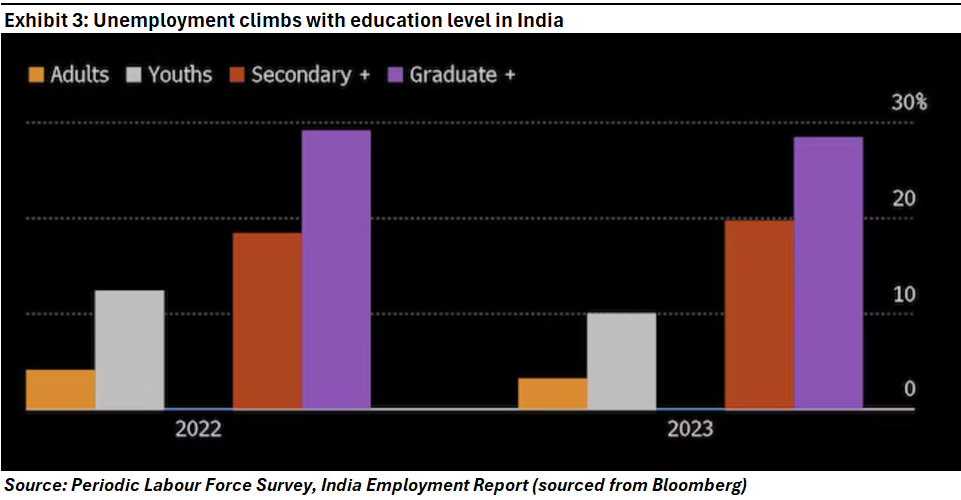

In fact, multiple layers of data now show that becoming a graduate actually reduces one’s employment prospects – see the exhibit below. As the Business Standard puts it:

“The jobless rate for graduates was 29.1 per cent, almost nine times higher than the 3.4 per cent for those who can’t read or write, a new ILO report on India’s labor market showed. The unemployment rate for young people with secondary or higher education was six times higher at 18.4 per cent.”(Source: https://www.business-standard.com/economy/news/young-indians-more-likely-to-be-jobless-if-they-are-educated-ilo-data-124032900038_1.html)

To understand how significantly graduation reduces one’s earnings profile in India, the book to read is Rama Bijapurkar’s brilliantly insightful “Lilliput Land” (2024). In exhibit after exhibit (see for example the opening exhibit of this note which is taken from ‘Lilliput Land’), Ms. Bijapurkar teases out data which shows, amongst other things, how graduates suffer in comparison to those who have simply passed their school leaving Class XII exams. Ms. Bijapurkar notes in her book:

“Even in the richest 10 per cent of households, which we have seen are discontinuously high earners, one-third only have graduate or above degrees, another third have stopped studying after school finals and a quarter have very little schooling.” [Emphasis is ours]

Given that the Indian economy is growing at a reasonably healthy rate, why do we have: (a) very high levels of graduate unemployment; and (b) no earnings uplift from university education? At Marcellus, with our modest resources, we have sought to address these questions in the remainder of this note. However, as we enter the AI transition era, the data shown above warrants a deeper investigation by authorities with far more resources than us regarding whether the Indian university system is actually fit for the purpose of helping the Indian economy develop (or whether the university system – along with the whole paraphernalia around test prep – represents a glorified form of distributed rent seeking in return for granting seemingly prestigious but low value credentials).

Does the Indian university system deliver what it is supposed to?

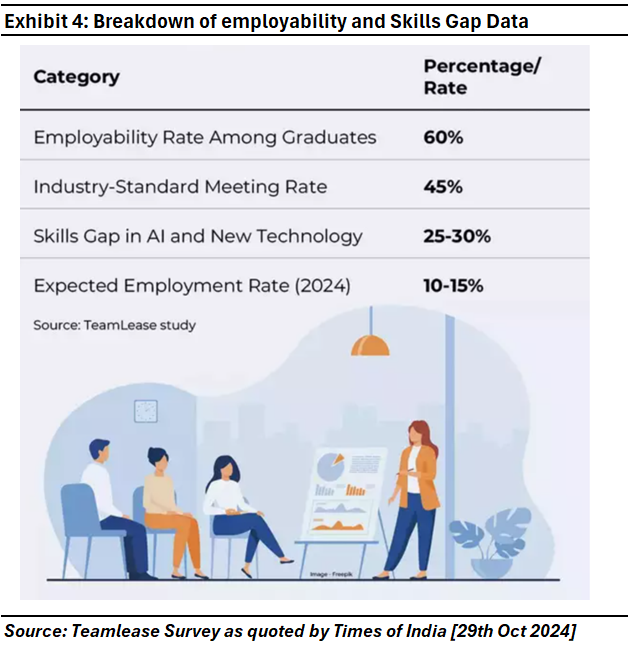

The concern that most employers voice about Indian graduates is many of them lack problem-solving skills. This in turn is of often attributed to the outdated curriculum taught at many universities in India. TeamLease, the recruitment & staffing firm, conducted a survey recently which highlights the employability challenge of Indian graduates:

“The report by TeamLease has delivered a sobering statistic: only 10% of the 15 lakh engineering graduates expected to pass out this year will find jobs. This stark figure underscores a deep-rooted problem in India’s education system: A massive disconnect between academic training and industry training, leaving millions of graduates underprepared and unemployed.

According to AR Ramesh, CEO of TeamLease Degree Apprenticeship, the calculation hinges on a number of factors, including the employability rate, industry demands, and a significant skills gap.

“To break it down, India produces approximately 1.5 million engineering graduates each year. Whilst 60% of them actively seek employment, only 45% meet industry standards in terms of skill readiness. Now with the additional demand-supply gap created by AI and advanced technology skills, this figure drops further to around 10-15%”, says Ramesh….

…Ramesh explains that the issue isn’t necessarily the lack of jobs but rather a mismatch in expectations and skill sets…Essentially, whilst jobs exist, they aren’t accessible to the majority of graduates due to their inability to meet the evolving demands of the tech-driven market…

A key challenge is the misalignment between academic curricula and industry expectation. Ramesh points out…the training these students receive is often outdated…” (Source: https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/education/news/pursuing-engineering-once-a-fad-now-a-dilemma-only-10-percent-of-15-lakh-graduates-likely-to-land-jobs-this-year/articleshow/114686084.cms)

Concerns such as these prompted the Economic Survey published in July 2024 to say that only 51% of Indian grads are employable. (Source: https://www.thehindu.com/business/budget/economic-survey-2023-24-only-51-percent-indian-graduated-employable-survey-says/article68432324.ece)

However, others have taken a harsher view of the employability of Indian gradates:

“At the institutional level, as reskilling and upskilling become a necessity, universities and vocational training institutes need to be closely plugged into changes in skill requirements and then quickly offer courses to provide the same. But Indian universities are still stuck in the old paradigm where three-year-degree courses do not make you worthy of a job anywhere, and even our engineers are largely unemployable. According to a National Employability Report (for engineers) by Aspiring Minds, which bills itself as an ‘employability solutions provider’, for every hundred engineers produced in 2015, barely 18 per cent were employable in IT services, less than 4 per cent in IT products, and about 40 per cent in lower-skill, non-functional roles in business processes outsourcing. The survey was based on a computer adaptability skill test and the sample covered around 150,000 students from more than 650 engineering colleges across India.” – R. Jagannathan in The Jobs Crisis in India (pg. 26; 2018).

In this telling of the graduate employment challenge, major problem is not so much on the demand-side; it is on the supply-side i.e., most of the graduates emerging from India’s universities do not have employable skills. That’s why they have few takers and that’s why even those graduates who get jobs get paid the same as a car driver in Mumbai.

Is the Indian economy capable of generating jobs for graduates on a large scale?

The demand-side challenge is more nuanced. Several researchers have found that over the past 20 years, India needs fewer and fewer incremental workers to power its economic growth engine. Long before AI came to the picture, automation of offices and robotization of factories was making India an increasingly capital-intensive economy.

“India Inc isn’t hiring as much as it used to. The pace of growth in net white collar employment has halved in 2023-24 from five years back. At ET study of the Sensex companies…showed such jobs grew 4.4% in FY24 compared to 8.4% in FY19” (Source: https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/jobs/hr-policies-trends/at-a-bunch-of-companies-white-collar-jobs-slip-into-the-red/articleshow/112575642.cms?from=mdr)

“According to the National Association of Software and Services Companies, or NASSCOM, data, automation and productivity improvements have drastically reduced the number of engineers required to produce every $1 billion of software exports. In 2009–10, the industry needed 31,846 engineers to produce that revenue; in 2015–16, it needed just over half that number, or 16,055 engineers.” – R. Jagannathan in The Jobs Crisis in India (pg. 79; 2018).

“According to the RBI working paper ‘Estimating Employment Elasticity of Growth for the Indian Economy’, published in mid-2014, every additional unit of growth in GDP creates fewer and fewer new jobs.17 The research paper, written by Sangita Misra and Anoop K. Suresh, drawing on data from several sources, concludes that employment elasticity is falling: [T]here has been a continuous decline in employment elasticity from the 1970s to 1980s to 1990s. During the 2000s till date (i.e., 1999–2000 to 2011–12), employment elasticity was about 0.20 (a shade higher than that of 0.19 per cent as estimated by Planning Commission till 2009–10). Employment elasticity was high (about 0.5 per cent) for the first half of 2000s. It declined significantly during the second half of 2000s. Notwithstanding an improvement during 2009–10 to 2011–12, it has remained lower than that of the first half of 2000s. For the post reform period as a whole (1993–94 to 2011–12), employment elasticity was placed at 0.18. Translated into plain-speak, this means every 1 per cent increase in GDP increases jobs by only 0.18 per cent. It implies that fast growth is essential, but even faster growth will not improve the employment elasticity. Theoretically, if India achieves 10 per cent growth for a considerable number of years, it would mean jobs will grow by a mere 1.8 per cent annually—hardly enough to take care of the numbers entering the jobs market in any year (about 12 million)” – R. Jagannathan in The Jobs Crisis in India (pg. 83; 2018).

AI is the latest in a long line of tech disruptions for the labour market

It is in this context – of India’s university not being upto the challenge of large-scale graduate skilling and India’s economy becoming increasingly less labour intensive – that AI adds a further layer of complication.

In many ways, the challenge that new technology poses to employment is neither new (it has been around since John Kay invented the Flying Shuttle in northern England at the beginning of the Industrial Revolution) nor a novel occurrence for India. The robotization & automation of India’s factories over the past decade had arguably a greater impact on the labour market. However, because factory automation hits blue collar employment rather than white collar, there isn’t as much angst or newspaper space dedicated to it. AI, on the other hand, hits the white-collar middle class where it hurts and exposes the inadequacy of universities around the world.

As far back as 2015, the World Economic Forum published the following piece whilst reviewing Geoff Colvin’s book titled ‘Humans Are Underrated: What High Achievers Know That Brilliant Machines Never Will’:

“There is nothing new about the idea that technology reshuffles which human skills are most valuable. That’s what machines do. (Ask your local blacksmith.) But this particular shuffle represents a historic shift: Machines are taking over not only manual labor but also cognitive labor.

For years, lawyers, doctors, and investment bankers have represented the pinnacles of skilled labor. But now, says Colvin, even these high-status, high-skill jobs are threatened by computers.

There’s legal software that can sift through case law and identify relevant precedents far faster than human lawyers. Computers can out-diagnose medical professionals…

We’ll still need human lawyers and human physicians and human investment bankers, but as technology improves and disseminates, we’ll need fewer of them.

But, Colvin argues, there is a bright spot amid the gloom, one thing humans can do that robots can’t: Be human. If our intellect can’t save us, our capacity for feeling might. And it’s those interpersonal skills — relationship-building, collaborating, empathy, and cultural sensitivity — that are poised to become top currency.

If you can’t beat the machines at being machines anymore, you can beat the machines at not being machines.”

(Source: https://www.weforum.org/stories/2015/08/what-is-the-most-valuable-skill-to-have-in-a-robot-economy/)

Kai-Fu Lee takes a similar view in his riveting multi-award-winning book ‘AI 2041’:

“Jobs that are asocial and routine, such as telemarketers or insurance adjusters, are likely to be taken over in their entirety. For jobs that are highly social but routine, humans and AI would work together, each contributing expertise. For example, in the future classroom, AI could take care of grading routine homework and exams, and even offering standardized lessons and individualized drills, while the human teacher would focus on being an empathetic mentor who teaches learning by doing, supervises group projects that develop emotional intelligence, and provides personalized coaching.

For jobs that are creative but asocial, human creativity will be amplified by AI tools. For example, a scientist can use AI tools to accelerate the speed of drug discovery. Finally, the jobs that require both creativity and social skills, such as Michael’s and Allison’s strategy-heavy executive roles in “The Job Savior,” are the ones where humans will shine.” – Kai-Fu Lee & Chen Qiufan. AI 2041: Ten Visions for Our Future (p. 351). Ebury Publishing. Kindle Edition.

Technology far outpacing education system is the root of the problem

And this is where we believe the heart of the problem lies with India’s university system. The skills necessary to thrive in the AI transition – social skills, creativity, empathy, emotional intelligence, relationship building, collaboration, cultural sensitivity, interpersonal skills – are NOT the skills that India’s university system is designed to impart. In fact, while the following has been said in the context of the American university system, it is also applicable India’s university system including the IITs and IIMs:

“The problem is that students have been taught that that is all that education is: doing your homework, getting the answers, acing the test. Nothing in their training has endowed them with the sense that something larger is at stake. They’ve learned to “be a student,” not to use their minds.” – William Deresiewicz in ‘Excellent Sheep: The Miseducation of the American Elite and the Way to a Meaningful Life (pg. 13; 2015).

And the same book, William Deresiewicz’s insightful & irreverent ‘Excellent Sheep’ – written a decade ago in the context of labour scarce America – contains another quote which we believe speaks to the heart of the graduate employment challenge in labour rich India, namely, the emphasis on rote learning and uselessness of the same in the age of AI:

“Graduates are said to have trouble “communicating and working in teams, and often struggle to see complex problems from a variety of angles”—exactly the kind of vision a liberal arts education instills. “Increasingly, anything you learn is going to become obsolete within a decade,” says Larry Summers, the former secretary of the Treasury and president of Harvard. “The most important kind of learning is about how to learn.”…

If Thomas Friedman is right, if the future belongs to those who can invent new jobs and industries rather than staffing existing ones, then it belongs to people with a broad liberal arts education…

Tony Wagner, author of The Global Achievement Gap, notes that even high-tech companies “place comparatively little value on content knowledge.”…

Information is freely available everywhere now; the question is whether you know what to do with it.” – William Deresiewicz in ‘Excellent Sheep: The Miseducation of the American Elite and the Way to a Meaningful Life’ (pg. 152; 2015).

Nandita Rajhansa and Saurabh Mukherjea work for Marcellus Investment Managers (www.marcellus.in). The views and opinions expressed in this material are those of the writers/authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy. This material is for informational and educational purposes only and should not be considered as financial, investment, or other professional advice. The inclusion of any book does not imply endorsement or recommendation by the writers or the publisher of this material

Note: the above material is neither investment research, nor investment advice. Marcellus does not seek payment for or business from this material/email in any shape or form. Marcellus Investment Managers Private Limited (“Marcellus”) is regulated by the Securities and Exchange Board of India (“SEBI”) as a provider of Portfolio Management Services. Marcellus is also a US Securities & Exchange Commission (“US SEC”) registered Investment Advisor. No content of this publication including the performance related information is verified by SEBI or US SEC. If any recipient or reader of this material is based outside India and USA, please note that Marcellus may not be regulated in such jurisdiction and this material is not a solicitation to use Marcellus’s services. All recipients of this material must before dealing and or transacting in any of the products and services referred to in this material must make their own investigation, seek appropriate professional advice. This communication is confidential and privileged and is directed to and for the use of the addressee only. The recipient, if not the addressee, should not use this material if erroneously received, and access and use of this material in any manner by anyone other than the addressee is unauthorized. If you are not the intended recipient, please notify the sender by return email and immediately destroy all copies of this message and any attachments and delete it from your computer system, permanently. No liability whatsoever is assumed by Marcellus as a result of the recipient or any other person relying upon the opinion unless otherwise agreed in writing. The recipient acknowledges that Marcellus may be unable to exercise control or ensure or guarantee the integrity of the text of the material/email message and the text is not warranted as to its completeness and accuracy. The material, names and branding of the investment style do not provide any impression or a claim that these products/strategies achieve the respective objectives. Further, past performance is not indicative of future results. Marcellus and/or its associates, the authors of this material (including their relatives) may have financial interest by way of investments in the companies covered in this material. Marcellus does not receive compensation from the companies for their coverage in this material. Marcellus does not provide any market making service to any company covered in this material. In the past 12 months, Marcellus and its associates have never i) managed or co-managed any public offering of securities; ii) have not offered investment banking or merchant banking or brokerage services; or iii) have received any compensation or other benefits from the company or third party in connection with this coverage. Authors of this material have never served the companies in a capacity of a director, officer, or an employee. This material may contain confidential or proprietary information and user shall take prior written consent from Marcellus before any reproduction in any form.