OVERVIEW

Not only is entrepreneurship in India very different from what it is in the United States, but it is also a different ball game as compared to salaried employment in the world’s fifth largest economy. With stable, salaried employment in the public and in the private sector a thing of the past, the core of the Indian middle class needs attitudinal retuning if it is to capitalize on the economic opportunities posed by this vast, underdeveloped free market economy.

“The real allocation of resources in a capitalist democracy happened in the market. Every dollar was a ballot…and power was distributed unevenly with rewards reflective of entrepreneurial ability with a dash of luck.” – Quinn Slobodian in ‘Hayek’s Bastards: The Neoliberal Roots of the Populist Right’ (p. 100). Penguin Books Ltd. Kindle Edition

Indian Unicorns from 300 years ago

Most Indians, including the authors of this piece, grow up on a steady diet of biographies of Western entrepreneurs. On most pavement bookstalls in India, you will find books on Steve Jobs, Elon Musk, and Bill Gates. If you go to Amazon.in and look at the business bestseller list, you will find that that too is dominated by North American authors like Morgan Housel, Jordan Peterson, Walter Isaacson, and Robert Kiyosaki.

However, historians are now documenting that India itself has a long, rich, & colourful history of entrepreneurship. In fact, large scale Indian entrepreneurship predates the corresponding phenomenon in the United States by at least a century. Lakshmi Subramanian’s terrific book “India Before the Ambanis” has this to say about Indian entrepreneurship & the broader business environment in India in the seventeenth century when the Mughals ruled supreme whilst America was still a British colony with independence a century away:

“Contemporaries were struck by the seamless absorption of metal and bullion into the subcontinent and echoed the sentiments that had been expressed centuries ago by Pliny the Elder, who referred to India as the sink of the world’s gold…Writing in 1674, surgeon and travel writer John Fryer noted how Bania brokers were experts…and that their whole desire was to have money pass through their fingers!… what is fairly clear is the fact that money was available in plenty in Mughal India and that men knew how to make it, accumulate it and redeploy it for social and commercial gain. Millionaires, particularly merchant millionaires, were, therefore, not an uncommon entity in several of the Mughal cities and emporia—Virji Vora, Shantidas Jhaveri, Mulla Abdul Ghafur and the Jagat Seths were embodiments of the prosperity that Mughal India enjoyed for at least two centuries, right until the middle of the eighteenth century….

Indian goods, especially textiles along with spices, sugar and a range of other items, were in demand across regions, satisfying the members of the provincial elites and aristocracies as well as in the larger world of the Indian Ocean. Indian cloth was especially valued among the rich and poor alike. The simultaneous rise of the Safavids in Persia and the Ottomans in Turkey helped configure a dynamic Indian Ocean economy, wherein the location of India as the dominant player and supplier of calico became critically significant. It was thus no coincidence that seventeenth-century India saw a massive expansion in the volume of international trade and shipping with ports like Surat, Hugli and Masulipatnam enjoying unprecedented levels of prosperity. The Mughal state valued bullion and by default invested in the maintenance of trading channels and infrastructure, the benefits of which merchants made full use of. The French traveller Jean Baptiste Tavernier was full of praise for Indian roads and conveyances, ‘and of the manner of travelling in India, which in my opinion, is not less convenient than all the arrangements for marching in comfort either in France or in Italy’.” – Lakshmi Subramanian in ‘India Before The Ambanis: A History of Indian Business, Money, and Economy’ (p. 26). Penguin Random House India Private Limited. Kindle Edition.

From the mid-nineteenth century onwards though the British did much to discourage and disadvantage Indian entrepreneurs so that imports from the UK could reign supreme in the vast Indian market. The British dislike for Indian entrepreneurs was inherited by the Indian officers of the ICS and when this class of officers took charge of Indian economy in 1947, their sceptical attitude towards commerce and business seeped through into independent India’s politics & policies.

It wasn’t until a Balance of Payments of crisis struck India in the summer of 1991 that the Indian entrepreneur was uncaged. In one of the remarkable double acts seen in democratic politics since World War II, then Prime Minister PV Narsimha Rao and Finance Minister Manmohan Singh not only rescued India from the crisis, but they also used the crisis as a staging ground to dismantle the ‘License Raj’ and break the chains shackling the Indian entrepreneur.

With economic liberalisation in 1991 came faster economic growth and the India that we live in and know was born. In Chapter 3 of our book “Behold the Leviathan: The Unusual Rise of Modern India”, we have described how after an interregnum spanning two centuries, policy & politics have once again swung in favour of Indian entrepreneurs in the 21st century.

Their Entrepreneurs, Our Entrepreneurs

That being said, entrepreneurship in India is different from what it is in the United States. This is not only because America’s per capita income is 20x higher than that of India but also because America’s social structure is very different from that of India. In particular, the role of the family in Indian businesses is critical whereas in America family-run businesses faded away after World War II as the listed public limited company became the dominant mode of enterprise. In addition, community and caste also play important roles in Indian businesses in a way that is no longer prevalent in America.

The centrality of the family and the community in Indian businesses mean that reward sharing between the employers & their employees follows a very different construct to what is seen in America. For example, whilst ESOPs are commonplace in America, ESOPs are prevalent in only a small minority of listed companies in India i.e. some of the large, listed companies and the venture capital owned companies. In practical terms, majority of the 1.4 mn companies registered to pay corporate tax in India don’t use ESOPs. Instead, if they want to give performance related incentives to employees, they use bonuses which are sometimes calculated as a share of the company’s profits.

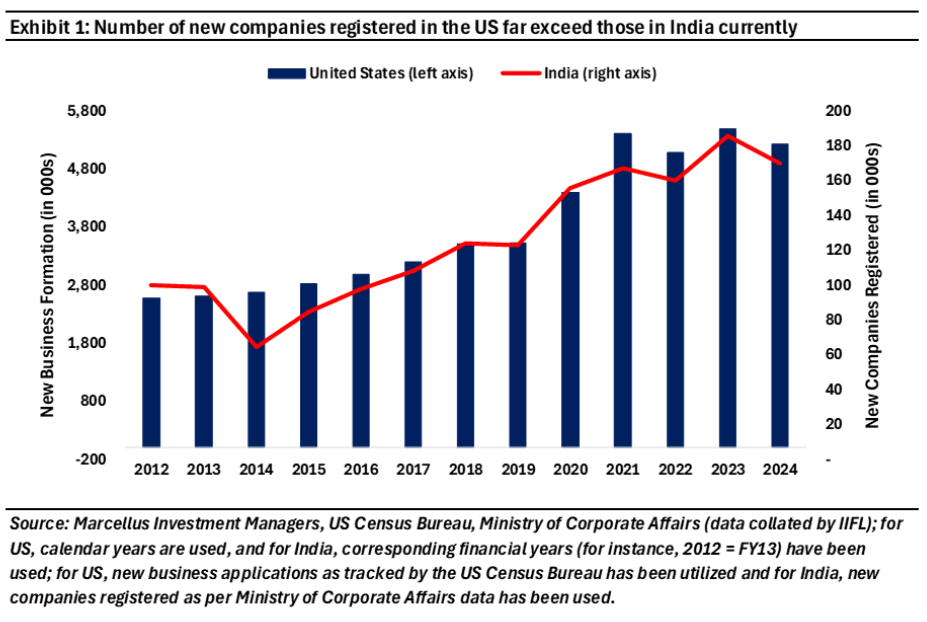

The downside of the family run company being the central entrepreneurial force in India alongside the much higher cost of capital in India compared to America (in excess of 12% in India vs half that amount in the US) means that the risk appetite and bet size of the Indian entrepreneur is much lower than that of his American counterpart. And yet because the cost of setting up a new business is lower in India than America, entrepreneurship is flourishing in India.

The Ten Commandments

So, if entrepreneurship in India is different from what it is in the West, what are the operating principles of successful entrepreneurship in the world’s largest democracy? The commandments listed below are basis our lived experience of setting up businesses in the West and in India. The list also draws upon our discussions over the past decade with Indian entrepreneurs and our reading of books published by Indian entrepreneurs.

The Ten Commandments of Indian entrepreneurship are:

1. Take risks

Take entrepreneurial risks. Train yourself to take Expected Value (EV) positive bets early in life and then spend your life making as many EV positive bets as you can. Make small bets initially but once you realise that the odds are in your favour, load up and go as big as you can afford to without putting your existence in jeopardy.

2. Simplify your life

Simplify your day-to-day life into a series of routines and processes which allow you to work hard, work intensely, work collaboratively and yet find time to relax, refresh and be creative.

3. Be patient

Be patient like Warren Buffett and play the infinite game. Know that is it likely that you will generate the vast majority of your wealth in the autumn of your life.

4. Embrace failure

Failure & success are like summer & winter i.e., they are a routine part of business life and should not be a source of exultation or heartburn. In fact, failure is an essential milestone en route to acquiring skills & learning.

5. Be happy ‘standing out’

If you do things that most others don’t, you will be criticised. Don’t abuse the haters. Enjoy the journey of ‘standing out’ from the crowd and walk down the path less trodden.

6. Be caring

Look after your colleagues, suppliers, distributors & customers. Nurture a corporate culture focused on learning, on process and on “means” (rather than “ends”, financial targets, etc).

7. Be curious, keep learning, ignore credentialing

Focus on the ‘inner scorecard’ rather than the ‘outer scorecard’. Focus on continuous learning, knowledge & skill acquisition rather than credentialing. Look for new experiences, new opportunities to acquire knowledge and build new skills

8. Relax & refresh (Don’t reflect)

Give yourself time to relax, recover and refresh. And when you are relaxing do NOT let your mind brood over past mistakes and try not to dwell on the challenges tomorrow will bring.

9. Build trust with relationships & experiences outside your comfort zone

Build relationships with a broad range of people especially people who are outside your community and/your comfort zone.

10. Nurture the next generation

Build a business which has multiple generations embedded in it. Train the next generation to be leaders, to understand the time value of money, to bring a disruptive point of view & fresh talent into the business.

As we will explain in ten blogs which will be published in the coming ten weeks, these commandments rather than standing alone, interplay with each other. So, for example, if you are willing to be patient and play the long game (Commandment 3), it is but inevitable that you will have your share of setbacks during that journey. Hence you will have to build mental resilience and learn to embrace failure (Commandment 4). And, if during this long journey, you want to keep yourself healthy, happy and motivated, you will have to pace yourself, give your yourself time to relax & refresh (commandment 8) and stay curious, keep reading and keep learning (commandment 7).

Nandita Rajhansa and Saurabh Mukherjea work for Marcellus Investment Managers (www.marcellus.in ). Amazon forms part of Marcellus’ Global Compounders Portfolio, a strategy offered by IFSC branch of Marcellus Investment Managers Private Limited. Hence, we as Marcellus, our immediate relatives and our clients may have interest and stakes in the mentioned stock. The stocks mentioned are for educational purposes only and not recommendatory. The views and opinions expressed in this material are those of the writers/authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy. This material is for informational and educational purposes only and should not be considered as financial, investment, or other professional advice. The inclusion of any book does not imply endorsement or recommendation by the writers or the publisher of this material.

The above material is neither investment research, nor investment advice. Marcellus does not seek payment for or business from this material/email in any shape or form. Marcellus Investment Managers Private Limited (“Marcellus”) is regulated by the Securities and Exchange Board of India (“SEBI”) as a provider of Portfolio Management Services. Marcellus is also a US Securities & Exchange Commission (“US SEC”) registered Investment Advisor. No content of this publication including the performance related information is verified by SEBI or US SEC. If any recipient or reader of this material is based outside India and USA, please note that Marcellus may not be regulated in such jurisdiction and this material is not a solicitation to use Marcellus’s services. All recipients of this material must before dealing and or transacting in any of the products and services referred to in this material must make their own investigation, seek appropriate professional advice. This communication is confidential and privileged and is directed to and for the use of the addressee only. The recipient, if not the addressee, should not use this material if erroneously received, and access and use of this material in any manner by anyone other than the addressee is unauthorized. If you are not the intended recipient, please notify the sender by return email and immediately destroy all copies of this message and any attachments and delete it from your computer system, permanently. No liability whatsoever is assumed by Marcellus as a result of the recipient or any other person relying upon the opinion unless otherwise agreed in writing. The recipient acknowledges that Marcellus may be unable to exercise control or ensure or guarantee the integrity of the text of the material/email message and the text is not warranted as to its completeness and accuracy. The material, names and branding of the investment style do not provide any impression or a claim that these products/strategies achieve the respective objectives. Further, past performance is not indicative of future results. Marcellus and/or its associates, the authors of this material (including their relatives) may have financial interest by way of investments in the companies covered in this material. Marcellus does not receive compensation from the companies for their coverage in this material. Marcellus does not provide any market making service to any company covered in this material. In the past 12 months, Marcellus and its associates have never i) managed or co-managed any public offering of securities; ii) have not offered investment banking or merchant banking or brokerage services; or iii) have received any compensation or other benefits from the company or third party in connection with this coverage. Authors of this material have never served the companies in a capacity of a director, officer, or an employee. This material may contain confidential or proprietary information and user shall take prior written consent from Marcellus before any reproduction in any form.