OVERVIEW

The networking of the Indian economy (through roads, phones, internet, low cost flights) has created immense churn in the stockmarket. Small companies who were formerly regional players are raising their sights and aiming to become national players. The rewards for those who succeed is a pan-India franchise and a place in the BSE500. Investors who buy these stocks before they fly into the BSE500 earn returns in excess of 40% per annum.

“The century after the Civil Was was to be an Age of Revolution – the countless, littlenoticed revolutions, which occurred not in the halls of legislatures…but in homes and farms and factories…so little noticed because they came so swiftly, because they touched Americans everywhere and every day.” – Daniel Boorstin in “The Americans: The Democratic Experience” (1973)

Churn in the BSE500 has surged…

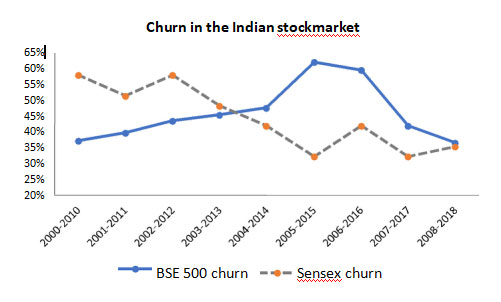

In the 1980s there was very little churn in the Indian stockmarket – if you were a large firm ensconced in the Sensex, you stayed there courtesy the License Raj. Then came the 1991 reforms and churn in the Sensex skyrocketed to 60% over the next decade i.e. 18 of the 30 companies that were in the Sensex in 1991 were ejected from the benchmark index by the turn of the century. Unfortunately, after those momentous reforms India’s leaders lost their mojo and in the 21st century as the pace of economic reform slowed, so did churn in the Sensex – see the chart below.

However, this reduction in churn amongst the largest listed companies hides dynamism elsewhere in the Indian stockmarket and, by inference, in the Indian economy. In particular, decadal churn in the broader benchmark, the BSE500, has risen steadily in the 21st century and was until a couple of years ago running at an incredible 60% i.e. of the 500 firms in the index at the beginning of the decade, 300 were ejected by the end of the decade [which also implies that 300 new firms found their way into the index].

Source: Marcellus Investment Managers using Thomson Reuters data. The chart shows the % of the stocks in the given index (BSE500 or Sensex) which were out of the index by the end of the ten year period after being in the index at the beginning of the period.

Churn in the BSE500 has slowed down in the last couple of years. Whilst we suspect that this might be due to demonetisation and GST (small firms found it harder to deal with these than larger firms), I have no way of being sure. However, as explained below, we reckon the last two years were an aberration – the operating environment for smaller firms has improved for the better in this century and that trend by and large should sustain going forward.

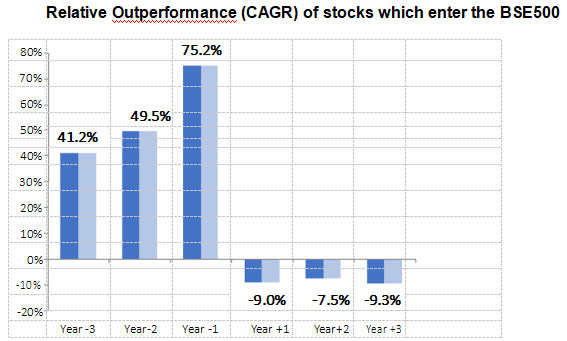

Source: Marcellus Investment Managers using Thomson Reuters, Ace Equity. Relative returns (relative to the BSE 500) are median CAGR of stocks that have been included in the BSE 500. For prior returns, returns are measured until 1 quarter preceding the quarter of entry. Period of BSE500 constituent data analyzed – 2002-2018.

From an investors’ viewpoint, even more exciting than the churn are the returns that entrants into the BSE500 produce as they fly into the index. As shown in the chart above, in the three year run-up to entering the BSE500, entrants outperform the index at a CAGR of 41%. Given that each year around 25 firms are entering the BSE500, such a trend clearly points to underlying economic drivers which are helping well run small firms explode into prominence. [Note: to enter the BSE500, a firm would have to have market cap of around Rs3,000 crores (or US$500mn). That in turn would imply PAT of around Rs150 crores (US$20m) and topline of around Rs3000 crores (US$450mn).]

…as smaller Indian firms discover a pan-India market

“Though not a single household household was wired for electricity in 1880, nearly 100 percent of US urban homes were wired by 1940, and in the same time interval the percentage of urban homes with clean running piped water and sewer pipes for waste disposal had reached 94 percent. More than 80 percent of urban homes in 1940 had interior flush toilets, 73 percent had gas for heating and cooking…In short, the 1870 houses were isolated from the rest of the world, but 1940 houses were ‘networked’, most having the five connections of electricity, gas, telephone, water and sewer…Networking inherently implies equality. Everyone, rich and poor, is plugged into the same electric, water, sewer, gas and telephone network. The poor may only be able to hook up years after the rich, but eventually they receive the same access.”

– Robert Gordon in “The Rise & Fall of American Growth” (2016)

Small/informal businesses flourish in an underdeveloped economy where due to the lack of availability of electricity, good roads, reliable communication networks and affordable credit, businesses can operate only a small scale and that too within the confines of their immediate locality. However, as the quote shown above from Robert Gordon suggests, the installation of “networks” – rail, electric, water, gas and telephone – in America between 1840 and 1920 rapidly formalised that economy and catalysed the rise of consumerism.

India seems to be going through period comparable to what America went through in the 50 years post the Civil War. Over the past ten years, the length of roads in India has increased from 3.9 million km to 5.6 million km (implied CAGR of 4.2%). The number of mobile phone subscribers has increased over the same period from 234 million to 1.2 billion (CAGR of 20%). The number of broadband users has increased from 3 million to 363 million (CAGR of 70%). A decade ago around 50 million Indians were taking flights each year. Now 3x as many Indians are flying each year (CAGR of 12%). 15 years ago only 1 in 3 Indian families had a bank account; now nearly all Indian families have a bank account.

These factors have made it easier for smaller companies to build pan-India franchises. Businesses that were local in nature are trying to become regional; those that were regional are seeking to become national. In fact, from what I see on my travels, many of the passengers taking low cost flights and staying in Oyo Rooms or in 3-star hotels are regional businessmen trying to grow their business elsewhere in the country. GST, looking beyond of the short term disruption caused by it, looks as if it might be another step forward in creating a more integrated economy.

Investment implications

“…La Opala has grown from a small family-run outfit to a National Stock Exchange-listed player with a market capitalisation of Rs 2,900 crore in under three decades. Revenues in FY16 stood at Rs 256 crore, up 10.5 per cent over the previous year, while net profit firmed to Rs 58.7 crore, up 28.9 per cent over FY15. From near-anonymity in the late 1980s, when La Opala started off, to near-dominance today (the company commands a 60 percent share of the Rs 360-400 crore opal and glassware market according to brokerage Nirmal Bang Securities) what has led La Opala to catapult ahead so remarkably?” – Forbes India, 26th May 2017 issue

The networking of the broader economy through better road & communication networks has allowed small firms to grow larger by conquering a specific niche nationally. For example, in FY08 Kajaria Ceramics, La Opala and Astral Poly had turnover of around Rs200-300 crores and their PAT was around Rs5-10 crores. Unsurprisingly, their market caps were around Rs 150 crores and they were a million miles from the BSE500.

Then came a magic ten year period in which Kajaria broke away to become the unquestioned king of the tile market, La Opala built the first national crockery company and Astral Poly made branded CPVC pipes the favourite of plumbers across India. Revenues compounded for these firms over the ten years at around 20% and PAT compounded at 30-40%. As a result, the share prices of these firms compounded at 40-60% per annum between FY08-18 (the same pattern shown in the second chart featured in this note). All three companies are now in the BSE500 with Kajaria’s market cap being Rs9K crores, La Opala’s Rs 3.2K crores and Astral’s Rs10.7K crores.

It goes without saying that not every small firm will be able to build a national niche. The winners will be those who have: (a) the work ethic to build a pan-India brand and national distributor-dealer networks; (b) the capital allocation skills to rationally & patiently invest in building long term competitive advantages rather than buying a flat in London; and (c) the skill and the drive to run efficient manufacturing operations and keep working capital cycles tight.

We reckon this trend of smaller firms surging will not only continue, it will become pronounced. Firstly, more firms who are well below the BSE500 will surge through to dominate their specific niches on a pan-India basis and become BSE500 stocks. In my new avatar, I spend most of my day searching for such stocks. Over the next few months, we will try to lay out a recipe for identifying the next generation of Kajarias and Astral Polys (i.e. companies who are outside the BSE500 but appear to be travelling – at a rapid rate – towards it).

Secondly, some of the hidden champions who have managed to break into the BSE500 will now use their spare free cashflows to move into adjacencies i.e. a new product segment which uses the same distribution channel. As explained in the bestselling book “The Unusual Billionaires”, Coffee Can stocks like Asian Paints, Marico and Astral Poly have created a template that these emerging champions can follow to take their leadership in one category and extend it across multiple categories.

Saurabh Mukherjea is the author of “The Unusual Billionaires” and “Coffee Can Investing: the Low Risk Route to Stupendous Wealth”. He is also the Founder and CIO of Marcellus Investment Managers Pvt Ltd.