OVERVIEW

A new generation of around 200,000 super rich families (or 1 million individuals) are making their spending muscle felt. Their wealth is a result of: (a) the financialization of physical assets; (b) the networking of India which has resulted in affluence spreading to smaller towns & cities; (c) the rise of a cadre of highly paid executives working in fast growing companies; and (d) the concentration of political & financial muscle in the hands of a handful of families in most towns & cities. Unafraid to indulge in conspicuous consumption, these 200k families, whom we call Octopi families, are now the main engines of consumption growth in India. It behooves us, therefore, to tilt our portfolios away from ‘mass’ and towards ‘class’ based consumption.

“A new wealthy class is exerting its will on the city—driving BMWs and Porsches, storming elite schools and colleges in Chanel and Birkenstock, and erecting grand towers while sipping on tandoori cold coffee and nibbling on kulhad pizza. It is the story of every tier-2 Indian city – toggling between new cash and kitsch.” – Antara Baruah (12th August 2023, The Print).

The rapid rise of the super-rich: data & measurement

India’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) has risen from US$ 607 bn in 2003 to US$ 3.75 tn in 2023. This 6x jump in national income over a 20-year period has been unevenly distributed. To be specific, a tiny elite of around 200,000 Indian families (or 1 million individuals) have become incredibly wealthy over the past 20 years. According to BCG, in the two decades between 1999-2019, the Indian elite’s wealth grew 15.8x. We can see the rapid rise of the super-rich Indian from three different types of data.

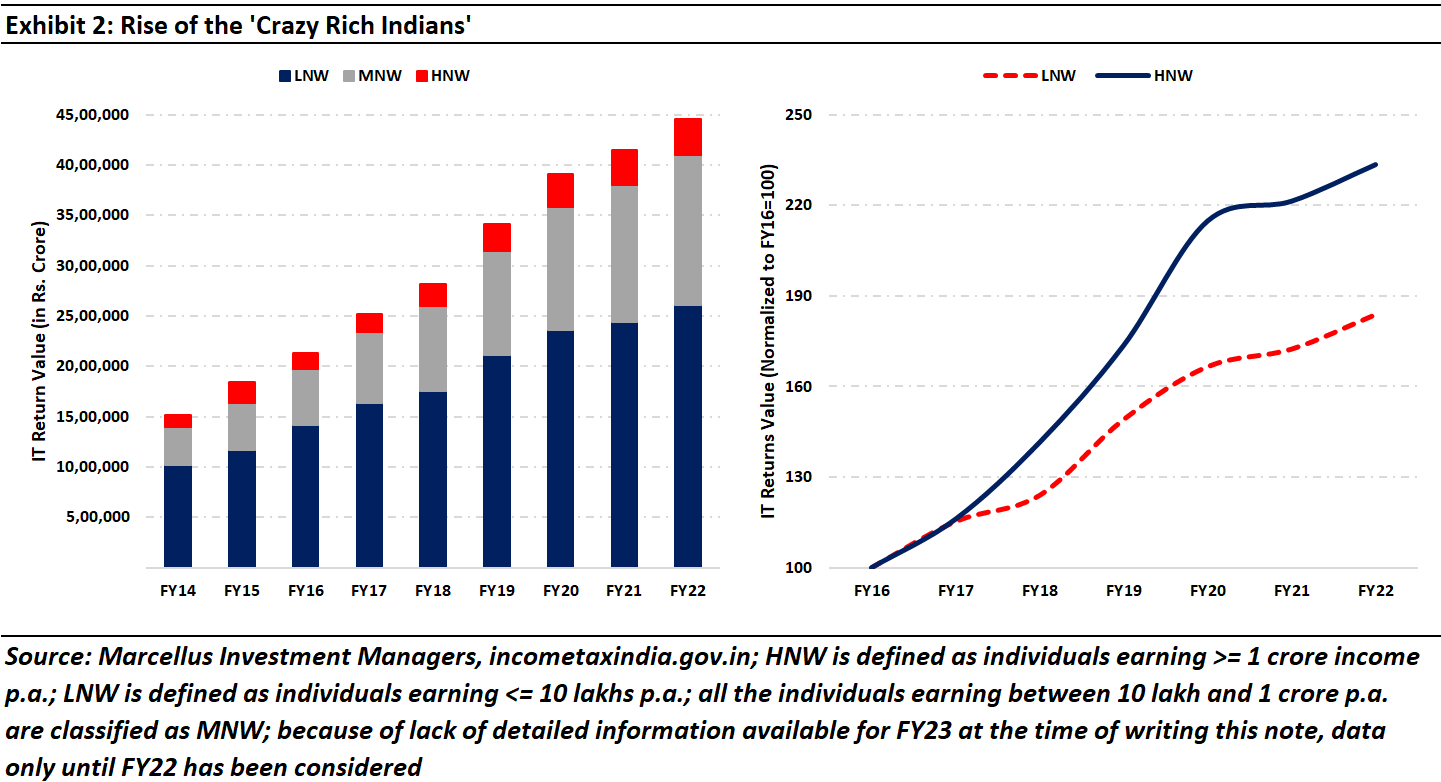

The first source is Income Tax data. “Over 2.69 lakh income tax returns were filed for income above Rs 1 crore for the financial year 2022-23, an increase of 49.4 per cent from the pre-pandemic year of 2018-19, while returns filed for income up to Rs 5 lakh rose by 1.4 per cent in the same period, as per e-filing data of the Income Tax Department. In absolute terms, 2.69 lakh income tax returns were filed for income above Rs 1 crore for financial year 2022-23 as against 1.93 lakh for 2021-22 and 1.80 lakh for 2018-19.” (Source: Indian Express, https://indianexpress.com/article/business/i-t-returns-filed-for-income-above-rs-1-crore-up-49-4-from-fy19-level-8879865/. Underlining is ours).

You can see the super-rich Indians’ rapid ascent in the Income Tax data in the charts below where ‘HNW’ is defined as those earning more than Rs. 1 crore per annum whereas ‘LNW’ is defined as those earning less than Rs. 10 lakhs per annum.

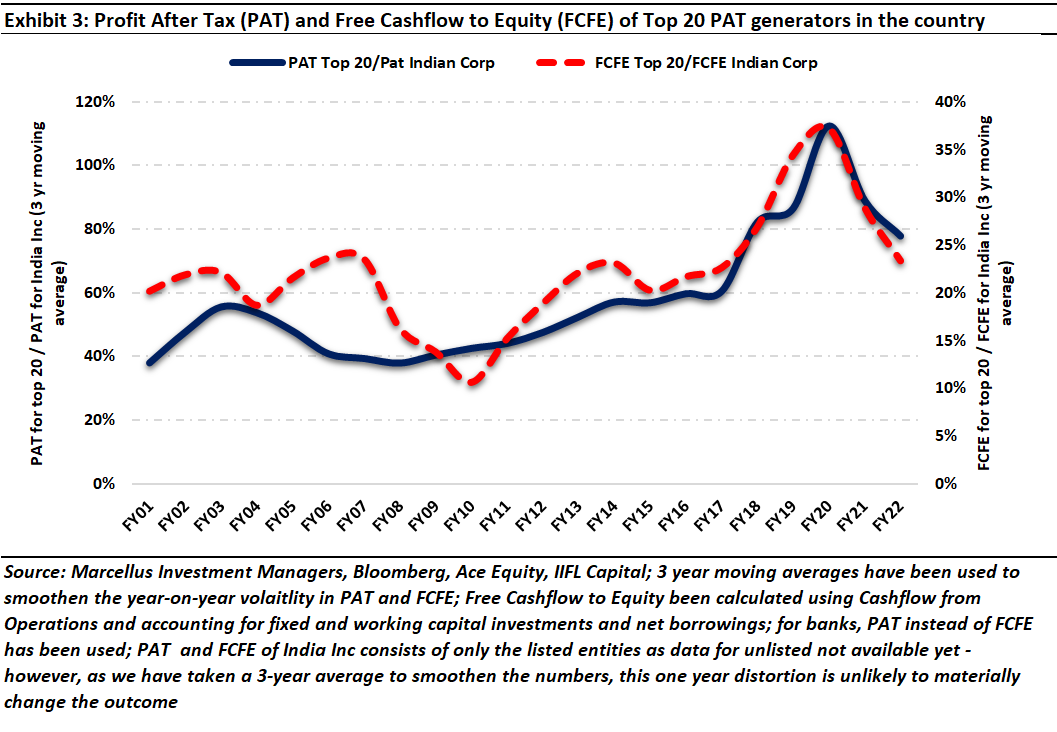

The second source of data which points to the rapid rise of a tiny super-rich elite is corporate profits. As highlighted in our 24th December 2022 note, ‘Winner Takes All’ in India’s New, Improved Economy, “Capitalizing on the exponential surge in digital transactions and the massive improvements in transport infrastructure and market structure seen over the past decade, a handful of Indian companies – no more than 20 – are taking home ~80% of the profits generated by the Indian economy. Simultaneously, a mere 20 companies account for 80% of the $1.4 trillion of wealth created by the Nifty over the past decade.”

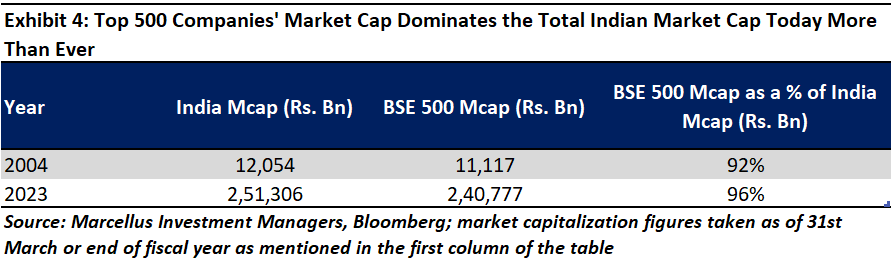

In fact, at every level of aggregation in the stock market, the trend of consolidation is visible. If we were to look at the market cap of BSE 500 companies vis-à-vis the total market cap in the country (see exhibit below), the prior’s share in the latter has increased significantly over the last 20 years i.e., the big keep getting bigger in India as every industry consolidates into the hands of 2-3 market leaders. In fact, what is even more noteworthy, is that out of the 24 lakh registered companies in the country, only ~66K companies generate income (or profits) greater than Rs. 1 crore (i.e., a meagre 2.7%)!

The third source of data on India’s new elite is the research published by wealth managers and their consultants:

- According to Credit Suisse, between 2020 and 2021, the number of US$ millionaires in India grew from 689K to 796K (source: Financial Times, 2023).

- BCG’s 2020 Global Wealth Report says that India has 112K individuals with wealth in excess of US$1 million.

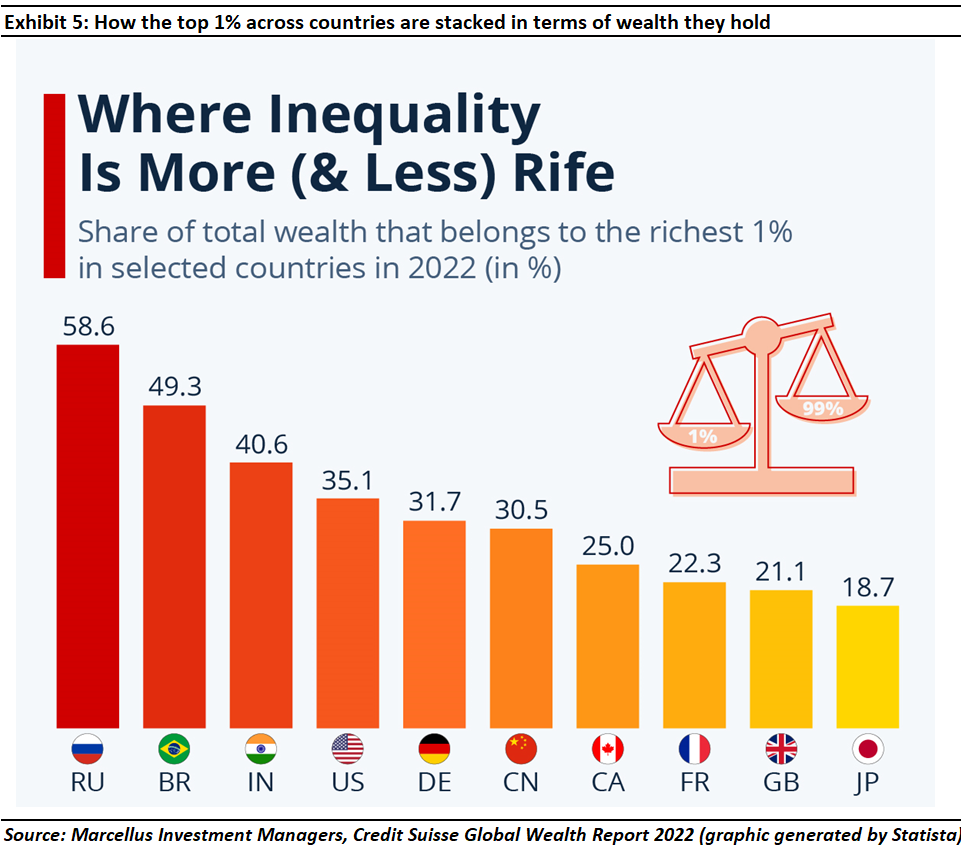

- According to Statista and Credit Suisse Global Wealth Report (2022), the share of wealth in India held by its richest 1% population (i.e., around 2 million families) is 40.6% (see exhibit below), following Russia (at 58.6%) and Brazil (at 49.3%).

Whilst general factors such as the rise in stock prices (the Nifty is up ~18x over the past 20 years – source: Bloomberg) and land prices (India’s national highway network has approximately trebled in the last 22 years; the price of land rises 60-80% when a highway goes past it) have helped the elite get rich, there are two very different wealth creation models in play in India. The first is a small-town model and the second is a big city model.

Small town wealth creation model

Let’s consider grain traders in a small town. For years, these traders were doing business conventionally, and a large part of it informally. But with demonetization and GST, most of them have formalized their business and now have access to the formal banking channels. The larger and smarter of these grain traders now takes a loan from a bank to open a cold storage to increase the shelf life of his products and sell them at a later date when prices are higher. As a result of this, over time he generates a surplus from selling grain. He now uses this surplus to secure a 2-wheeler dealership. As that dealership flourishes, he uses his enhanced surplus to open a car dealership.

By this time, he has generated considerable clout within the town (financially as well as in terms of his social status). Leveraging this clout, he gets his son into the local municipal corporation (or zila parishad). Over the next few years, his son rises in the local political hierarchy. Father & son then combine to get contracts for local road construction/repair. Profits from these local construction contracts further enhances the family’s surplus which they can then use to become local real estate developers. Thus, over the course of a decade a mini conglomerate is created which consolidates financial, social, as well as political power in that town and this conglomerate will steadily push its tentacles into every economically lucrative activity in that area – hence the term ‘Octopus’.

Our travels across India over the past decade have shown us that:

- A town with less than 0.5 million people will have 20 such families who will account for 80% of the wealth in that town.

- A city with 1 million people will have 50 such families who will account for 80% of the wealth in that city.

- A tier 2 city like Pune or Lucknow will have 100-300 such families who will account for 80% of the wealth in that city; and

- Major metros like Mumbai and Delhi will have a few thousand such families who will account for 80% of the wealth in that city.

Thus, at the national level around 200K such families (or between 700K – 1 million individuals) end up controlling 80% of India’s wealth.

Big city wealth creation model

The big city octopi operate in a different way to their small-town cousins. In particular, they are likely to have a high skill quotient in terms of technical qualifications which they will deploy to get well paid jobs in India Inc. As India’s leading companies continue gunning out profit growth of 20% per annum, the number of highly paid executives who manage these companies continues to burgeon. To hold on to their best talent, these companies will:

- Pay their executives well. The Economic Times says that in the listed company universe, there are 1,161 individuals who have an annual pay packet of Rs 1 crore or more. (source: In the last three years, India has added almost 58,000 crorepati taxpayers—a jump of 51%. What has scripted this unusual trend? – The Economic Times)

- Give their executives equity-based compensation which will then compound with the share price of the company thus implying at the market-wide level around 4x growth in wealth every decade.

Furthermore, the most ambitious of the corporate octopi are likely to quit to create a start-up where a combination of their equity ownership alongside venture capital or private equity funding will make them dollar millionaires in the span of a few years.

Thus, the big city octopi will be a combination of listed company owners (there are around 6000 such families in India), VC & PE backed companies’ owners (which we estimate are approximately 680 – assuming an average of 3 rounds are conducted per company), and the senior talent working in these companies.

Case studies of super-rich families

‘Ghari’: – RSPL’s (previously Rohit Surfactants’) Ghari detergent is a ubiquitous brand today across India. From humble beginnings in Kanpur (Uttar Pradesh), RSPL’s Ghari detergent today commands a share of approximately 20% in the $3.75 billion detergent industry in India (source: IIFL Research). Apart from this, RSPL also has forayed into dairy, footwear, renewable energy (they have 5 wind power plants with an installed capacity of 50.1 MW), and real estate (source: website). Had this Kanpur-based company been a listed entity, its owners would be dollar billionaires.

‘Dainik Bhaskar’ (DB Corp): The Bhopal based Agarwal family started with just one Hindi daily back in 1958 called Dainik Bhaskar. Today, this daily is the most popular and circulated daily in the entire country. Over the years, DB corporation (controlled to this day by the Agarwal family) has sought to enter other verticals like power and real estate. Although they haven’t been as successful in these as in their print business, it is the entrepreneurial talent of this family which has made Dainik Bhaskar become what it is today. Even within the media vertical, DB Corp has forayed into radio and digital media (source: website). DB Corp’s market cap is ~Rs. 4K crores and the Agarwal family owns ~72% of the listed entity.

Investment implications

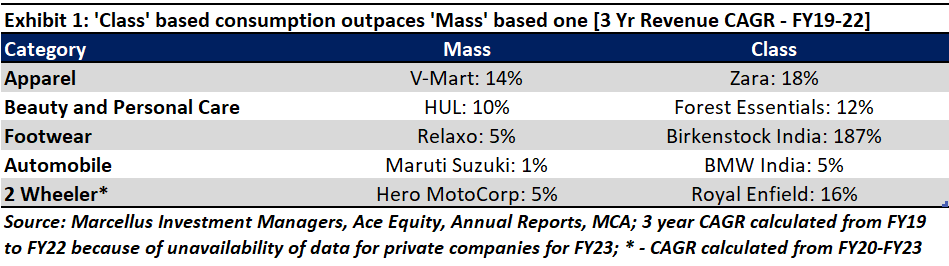

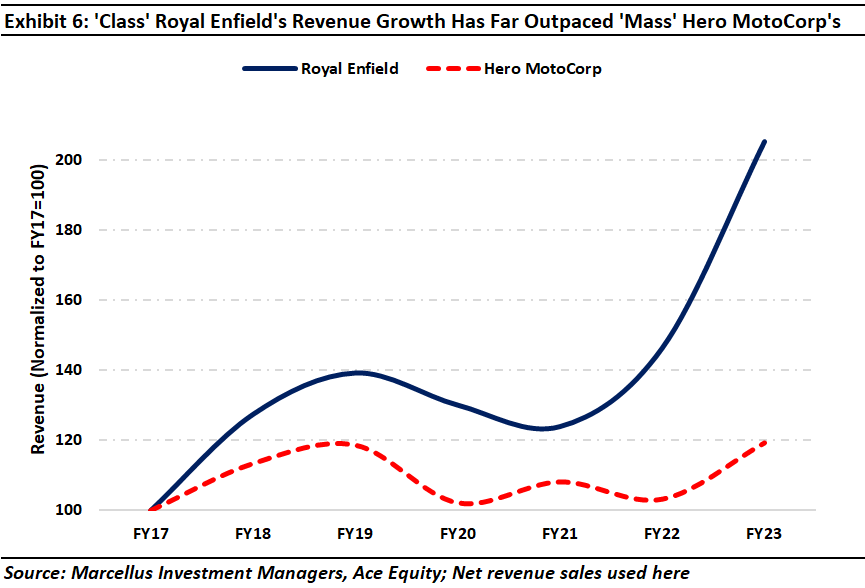

As is evident from Exhibit 1, companies whose products & services are a play on ‘class-based’ consumption are growing faster than companies who cater to the masses. Our investments seek to capitalize on this trend. We have cited three examples below of investments from Marcellus’ portfolios:

Titan: Titan is by an order of magnitude India’s most profitable jeweler (Tanishq plus Caratlane account for ~95% of Titan’s profits). The firm also has 60% market share of the watch market in India (watches account for 9% of Titan’s profits). Titan is also India’s largest retailer of eyewear through its 250+ Eye Plus stores (eyewear accounts of 2% of Titan’s profits). Four years ago, Titan launched Taneira, a rapidly growing chain of ~50 stores selling expensive sarees.

Kotak Mahindra Bank: Kotak Private Banking is one of the oldest and the most respected Indian private banking institutions, managing wealth for 51% of India’s top 100 families (Source: Forbes India Rich List 2021), with clients ranging from entrepreneurs to business families, and professionals. Leaving aside its lending business, Kotak also has a rapidly growing asset management business with Rs 3.6 tn of assets under management (accounting for 4% of the bank’s profits), and a large stockbroking business (accounting for 6% of the bank’s consolidated profits).

Eicher Motors:With its iconic Royal Enfield brand’s ‘Classic 350’, Eicher Motors was the first player in the two-wheeler space to launch a product aimed at the octopi customer base. Following this game-changing launch in 2009, Royal Enfield then built a wide distribution network coupled with various new model launches. Consequently, from FY13 to FY23, Royal Enfield sales have grown 6x from 121,000 units in FY13 to 735,000 units in FY23 in the domestic market. Royal Enfield now has 90% share in the Premium Motorcycle segment in India.

We are increasing our investments on this theme, about which we will write more in the months to come.

Nandita Rajhansa and Saurabh Mukherjea work for Marcellus Investment Managers (www.marcellus.in). Amongst the companies mentioned in this note, V-Mart, Eicher Motors (Royal Enfield), Titan, Kotak Mahindra Bank, and Trent (Zara) are part of Marcellus’ portfolios. Nandita and Saurabh may be invested in these companies and their immediate relatives may also have stakes in the described securities.

If you want to read our other published material, please visit https://marcellus.in/blog/

Note: the above material is neither investment research, nor investment advice. Marcellus does not seek payment for or business from this material/email in any shape or form. Marcellus Investment Managers Private Limited (“Marcellus”) is regulated by the Securities and Exchange Board of India (“SEBI”) as a provider of Portfolio Management Services. Marcellus is also a US Securities & Exchange Commission (“US SEC”) registered Investment Advisor. No content of this publication including the performance related information is verified by SEBI or US SEC. If any recipient or reader of this material is based outside India and USA, please note that Marcellus may not be regulated in such jurisdiction and this material is not a solicitation to use Marcellus’s services. This communication is confidential and privileged and is directed to and for the use of the addressee only. The recipient, if not the addressee, should not use this material if erroneously received, and access and use of this material in any manner by anyone other than the addressee is unauthorized. If you are not the intended recipient, please notify the sender by return email and immediately destroy all copies of this message and any attachments and delete it from your computer system, permanently. No liability whatsoever is assumed by Marcellus as a result of the recipient or any other person relying upon the opinion unless otherwise agreed in writing. The recipient acknowledges that Marcellus may be unable to exercise control or ensure or guarantee the integrity of the text of the material/email message and the text is not warranted as to its completeness and accuracy. The material, names and branding of the investment style do not provide any impression or a claim that these products/strategies achieve the respective objectives. Further, past performance is not indicative of future results. Marcellus and/or its associates, the authors of this material (including their relatives) may have financial interest by way of investments in the companies covered in this material. Marcellus does not receive compensation from the companies for their coverage in this material. Marcellus does not provide any market making service to any company covered in this material. In the past 12 months, Marcellus and its associates have never i) managed or co-managed any public offering of securities; ii) have not offered investment banking or merchant banking or brokerage services; or iii) have received any compensation or other benefits from the company or third party in connection with this coverage. Authors of this material have never served the companies in a capacity of a director, officer or an employee.

This material may contain confidential or proprietary information and user shall take prior written consent from Marcellus before any reproduction in any form.