OVERVIEW

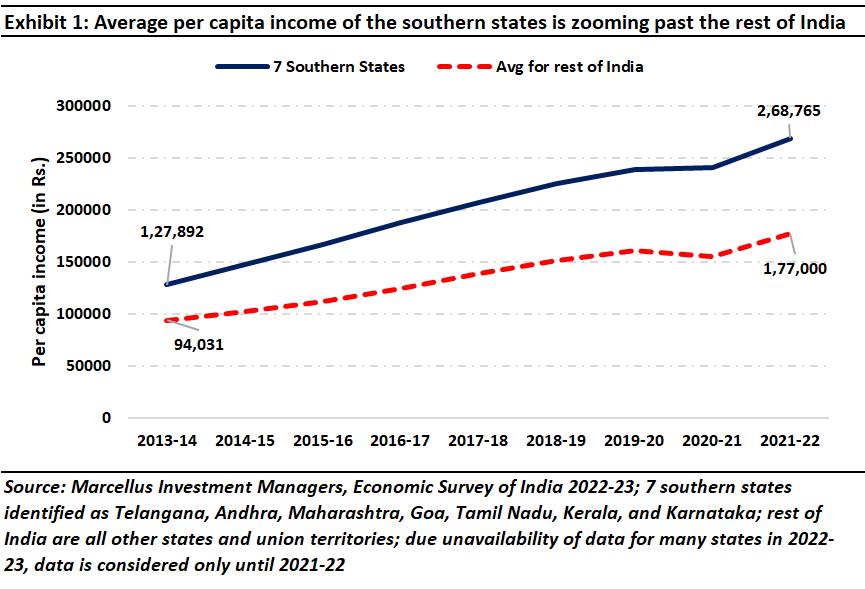

Per capita income for seven ‘southern’ states (Tamil Nadu, Telangana, Andhra, Kerala, Karnataka, Goa, and Maharashtra) has grown at an average 10% CAGR between FY14-22. These states, which account for 30% of India’s population and 45% of India’s GDP, now have an average per capita income of ~Rs 2.7 lakhs ($3,300), 50% higher than that of the Rest of India. A decade ago, the corresponding ‘South vs Rest’ gap was 35%. As the south relentlessly pulls away from the rest of India, we are looking to have an over-representation of southern India focused companies in our portfolios.

“Consider a child born in India. Firstly, this child is far less likely to be born in southern India than in northern India, given the former’s lower rates of population growth.

But let’s assume she is. In which case, she is far less likely to die in the first year of her life given the lower infant mortality rates in south India compared with the rest of the country.

She is more likely to get vaccinated, less likely to lose her mother during childbirth, more likely to have access to child services and receive better early childhood nutrition.

She will also go on to be a mother to fewer children, who in turn will be healthier and more educated than her.” – RS Nilakantan, author of ‘South vs North: India’s Great Divide’, quoted by the BBC in September 2022.

Introduction

Over the past decade, India has seen rapid development on several fronts. The national highway network saw a near doubling from ~79K km in 2012 to ~140K km in 2022, domestic air travel passengers more than trebling from ~54 mn in 2009 to ~170 mn in 2019, households with broadband connections grew ~7x from ~20 mn in 2013 to ~137 mn in 2023, the number of bank accounts grew ~3x from ~100 crores in 2015 to ~300 crores in 2023. And overall GDP grew from USD 1.8 tn in FY13 to USD 3.75 tn until June 2023.

Interestingly, whilst infrastructure development can be seen all across the country, not all regions are benefitting equally. The south, which has always been at the vanguard of India’s social and economic progress, is increasingly racing far ahead of the rest of the country. There are three dimensions along which the south is becoming a more powerful economy than the rest of India:

- Per capita income: Per capita income for the seven southern states has grown at an incredible average 10% CAGR over FY14-22 to now reach ~Rs 2.7 lakhs ($3,300). The corresponding number for the rest of India is 8%. A 2% per annum growth differential means that from being 35% richer than the rest of the country in FY14, the seven southern states are now 50% richer.

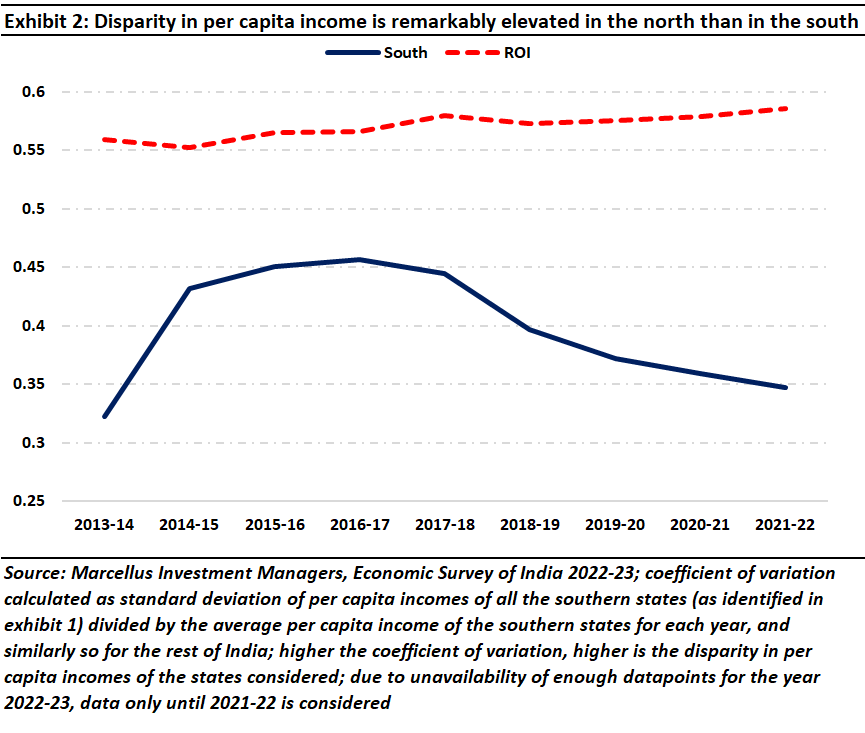

- More equal geographical dispersion of wealth: As the southern states move towards becoming second world economies (in terms of per capita income), the disparity of wealth between these seven states is narrowing i.e., the southern states are becoming more uniformly prosperous. This can be seen in Exhibit 2 which uses the coefficient of variation (i.e., standard deviation / average) as a measure of dispersion. In contrast, the rest of India is becoming more dissimilar as the country continues to grow at a healthy rate.

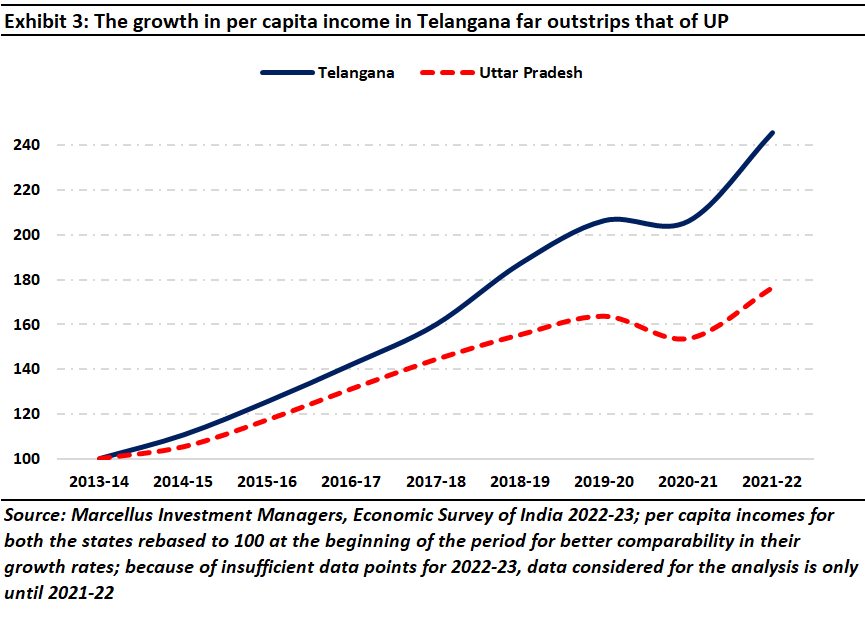

- Large clusters capable of sustained economic development: Both Indian and foreign companies naturally prefer setting up operations in parts of the country where skilled labor is readily available, where the transport infrastructure is well established and where the rule of law can be taken for granted. The South already has several economic clusters with per capita income above $3000 per annum, namely, Goa, Karnataka (specifically, the area around Bengaluru), Tamil Nadu (specifically, the areas around Chennai, Hosur, and Coimbatore), Telangana (specifically, the area around Hyderabad). The North in contrast just has Delhi (more generally, the National Capital Region spanning Gurgaon & Manesar in Haryana and Noida in UP) and Gujarat where per capita income is above $3000. With the South already having more economic clusters, there is a more developed ecosystem with availability of skilled labor and robust transport infrastructure, among others, which makes it preferable for both Indian and foreign companies to set up new operations in the south. In the North, barring the National Capital Region and Gujarat, one rarely hears about new operations being set up. The result of this can be seen in Exhibit 3 – a booming southern state like Telangana has more than doubled its per capita income in the past six years. In fact, Telangana’s per capita income is now more than $4000.

Why has the South surged ahead of the rest of India?

“The market alone cannot determine the appropriate level and location of public infrastructure investment, or rules for the settlement of labor disputes, or the degree of airline and trucking regulation, or occupational health and safety standards. Each one of these questions is “value-laden” to some extent, and must be referred to the political system. And if that system is going to adjudicate these conflicting interests fairly and in a way that receives the consent of all of the major actors within the economy, it must be democratic. A dictatorship could resolve such conflicts in the name of economic efficiency, but the smooth functioning of a modern economy depends on the willingness of its many interdependent social components to work together. If they do not believe in the legitimacy of the adjudicator, if there is no trust in the system, there will be no active and enthusiastic cooperation of the sort required to make the system as a whole function smoothly…Shared cultural values build trust and lubricate, so to speak, the interaction of citizens with one another.” – Francis Fukuyama in ‘The End of History and the Last Man’ (1992) [Underlining is ours]

In his landmark publication, ‘The End of History and the Last Man,’ Francis Fukuyama has explained how trust in a society is intricately linked to the development of large industrial organizations. If people trust each other to follow an unwritten set of social rules (which are implicitly understood by all), then doing business costs less. On the other hand, people who do not trust each other will end up co-operating only under the aegis of a formal set of rules & regulations [and this will impose an ongoing cost of doing business].

Basis our travels across India over the past 15 years, southern India comes across as a higher trust society than the rest of the country. Part of the reason for this seems to be that major conflicts around caste seem to have already played out in south India by the 1960s. As VS Naipaul explains in ‘India: A Million Mutinies Now’ (1990):

“Twenty years after the independence of India…After my introduction to the brahmin culture of the South, this was my introduction to the revolt of the South: the revolt of South against North, non-brahmin against brahmin, the racial revolt of dark against fair, Dravidian against Aryan. The revolt had begun long before; the brahmin world I had come upon in 1962 was one that had already been undermined.

The party that had won the state election in 1967 was the DMK, the Dravidian Progressive Movement. It had deep roots; it had its own prophet and its own politician-leader, men who were its equivalents of Gandhi and Nehru, men whose careers had run strangely parallel with the careers of the mainstream Indian independence leaders….And what that victory in 1967 meant was that the culture to which I had been introduced…the culture which had appeared whole and mysterious and ancient to me, had been overthrown.” [Underlining is ours.]

Whilst the caste system still likely prevails in south India, it isn’t an all-encompassing feature of daily business life. In contrast, according to commentators, barring the National Capital Region, caste and upper caste dominance still seems to be central to daily business life in northern India. As Harish Damodaran explains in ‘India’s New Capitalists’ (2008):

“Non-Brahmin mobilizations in the Madras and Bombay Presidency areas from the turn of the last century, in fact, had a dual impact. Firstly, they created a middle class with a reasonably broad social base. Secondly, by redefining and tweaking conventional social hierarchies, they forced the Brahmins and other upper castes to explore alternative career paths and become entrepreneurs themselves in the bargain.

Besides education and affirmative action, the factor that has contributed to a considerable ‘democratization of capital’ in the South is the absence of stranglehold over business by traditional mercantile and banking communities. Not that they did not exist; but the Chettiars and Komatis were nowhere as overbearing in the money and commodity markets as the ubiquitous northern Bania.”

One specific manifestation of southern India being a higher trust society than the rest of the country is that on average across the seven southern states, the rate of murder per lakh of population is 1.9 whereas the average for the rest of India is 2.2 [Source: National Crime Record Bureau, Ministry of Home Affairs (2021)].

Another consequence of the South being a less fractured society with higher levels of trust is that the nature of capitalism in the South is more inclusive than that in the rest of India. Harish Damodaran lays out this contrast eloquently in the context of the sugarcane industry:

“…this ‘inclusive capitalism’ has been more a feature of southern and, to some extent, western India. Take, for instance, the sugar industry in the South, which cannot possibly be identified with any particular community. Thus, we have EID Parry (Nattukottai Chettiar), Sakthi Sugars, Bannari Amman Sugars and Dharani Sugars (Gounders), Thiru Arooran Sugars (Mudaliar), Ponni Sugars (Brahmin), Rajshree Sugars (Naidu), Andhra Sugars and KCP Sugar (Kammas), GMR Industries (Komati), Gayatri Sugars (Reddy), Kothari Sugars (Gujarati Bania/Jain) and Empee Sugars (Ezhava).

This is not so in the North, where businessmen tend to be uniformly Bania–Marwaris or Khatris. The Jats (both Hindu and Sikh), Yadavs, Gujjars, and other intermediate castes produce the bulk of its sugarcane, paddy, wheat, cotton, oilseeds and milk, but rarely does one find sugar millers, branded rice makers, grain exporters, textile tycoons, solvent extractors, and dairy processors from these communities.

Things are better in the West, where the co-operative movement has enabled peasant castes like the Marathas and Patidars to make a successful entry into industry.” (Source: India’s New Capitalists by Hareesh Damodaran)

The networking of India and the advent of GST has, if anything, hastened the pace at which the South is pulling away from the rest of the country because:

- Pre-GST firms had some tax incentives to locate in tax exempt northern states like Himachal Pradesh and Uttaranchal. Now these tax incentives are no longer relevant.

- When India’s road & telephone infrastructure was rickety, firms had incentives to locate their factories closer to their customers. The pre-GST indirect tax system also encouraged this. In the post-GST world, with high quality highways rippling across the land, firms now locate factories where they have access to skilled labor and where law & order issues are not present. That swings the balance in favor of southern India.

Effectively, the South is now India’s domestic equivalent of an efficient east Asian economy, and the rest of India is increasingly going to ‘import’ what it needs from the south.

Investment implications

Historically, some of our largest portfolio positions have been in companies which have rapidly grown their southern Indian footprint. For example:

HDFC Bank is the largest and the most profitable private bank in the country. No other bank in India has been able to match this bank’s relentless compounding over the past three decades. In the last 2 years, HDFC Bank’s employee growth has been to the tune of 97% in the South and West regions versus 45% in the North. This has been on the back of 60% employees employed by HDFC Bank being in the South and West region in FY21 itself, pointing to the greater emphasis on the southern region of the country to capture massive talent pools, resulting in the creation of a financial behemoth.

Kotak Mahindra Bank – One of the best managed banks in India, Kotak Mahindra Bank’s footprint has steadily risen across the country. Interestingly though, the bank’s footprint (as measured by number of bank branches) has increased almost twice as fast in the West and South than in the North in the last 5 years. Remarkably, this growth is on the back of 64% of all branches being in the West and South region in FY18 itself, indicating further deepening of financial connectivity in the South.

Titan – Given that the south is more prosperous than the rest of the country, it is but natural that the largest driver of jewelry demand is southern India. According to research by CRISIL and MI&A Research, the south accounts for 45% of India’s jewelry demand [similar to the south’s share in India’s GDP].

In fact, if we were to look at Titan’s flourishing line of Taneira stores (which retail premium sarees), until FY18, they had just two stores both of which were in Bengaluru. Today, more than a third of the Taniera stores are in the south where they compete with strong regional brands like Nalli’s and Pothys.

Asian Paints – Having compounded shareholders’ wealth at 25% p.a. over the last 30 years, Asian Paints is a juggernaut showing no signs of fatigue and the south is playing a critical role in helping shareholders like us compound our wealth through it. Specifically, Asian Paints’ Beautiful Homes service, which is a premium proposition by the company to cater to the growing demand by customers to get customized home décor solutions has 48% of its outlets in the south.

As the south relentlessly pulls away from ROI, we are looking to have an over-representation of southern India focused companies in our portfolios. You will hear more from us on this subject in the coming months.

The main investment risk that the construct outlined in this note creates is that by 2026 – when India has to conduct its next exercise to determine which state gets how many seats in Parliament – the south might rebel against having very low representation in the lower house of Parliament [currently the South has only 177 of the total 538 seats in Lok Sabha] despite being the main generator of the Indian Exchequer’s tax revenues.

Nandita Rajhansa and Saurabh Mukherjea work for Marcellus Investment Managers (www.marcellus.in). Amongst the companies mentioned in this note, HDFC Bank, Kotak Mahindra Bank, Titan, and Asian Paints are part of Marcellus’ portfolios. Nandita and Saurabh may be invested in these companies and their immediate relatives may also have stakes in the described securities.

Note: the above material is neither investment research, nor investment advice. Marcellus does not seek payment for or business from this material/email in any shape or form. Marcellus Investment Managers Private Limited (“Marcellus”) is regulated by the Securities and Exchange Board of India (“SEBI”) as a provider of Portfolio Management Services. Marcellus is also a US Securities & Exchange Commission (“US SEC”) registered Investment Advisor. No content of this publication including the performance related information is verified by SEBI or US SEC. If any recipient or reader of this material is based outside India and USA, please note that Marcellus may not be regulated in such jurisdiction and this material is not a solicitation to use Marcellus’s services. All recipients of this material must before dealing and or transacting in any of the products and services referred to in this material must make their own investigation, seek appropriate professional advice. This communication is confidential and privileged and is directed to and for the use of the addressee only. The recipient, if not the addressee, should not use this material if erroneously received, and access and use of this material in any manner by anyone other than the addressee is unauthorized. If you are not the intended recipient, please notify the sender by return email and immediately destroy all copies of this message and any attachments and delete it from your computer system, permanently. No liability whatsoever is assumed by Marcellus as a result of the recipient or any other person relying upon the opinion unless otherwise agreed in writing. The recipient acknowledges that Marcellus may be unable to exercise control or ensure or guarantee the integrity of the text of the material/email message and the text is not warranted as to its completeness and accuracy. The material, names and branding of the investment style do not provide any impression or a claim that these products/strategies achieve the respective objectives. Further, past performance is not indicative of future results. Marcellus and/or its associates, the authors of this material (including their relatives) may have financial interest by way of investments in the companies covered in this material. Marcellus does not receive compensation from the companies for their coverage in this material. Marcellus does not provide any market making service to any company covered in this material. In the past 12 months, Marcellus and its associates have never i) managed or co-managed any public offering of securities; ii) have not offered investment banking or merchant banking or brokerage services; or iii) have received any compensation or other benefits from the company or third party in connection with this coverage. Authors of this material have never served the companies in a capacity of a director, officer, or an employee. This material may contain confidential or proprietary information and user shall take prior written consent from Marcellus before any reproduction in any form.