OVERVIEW

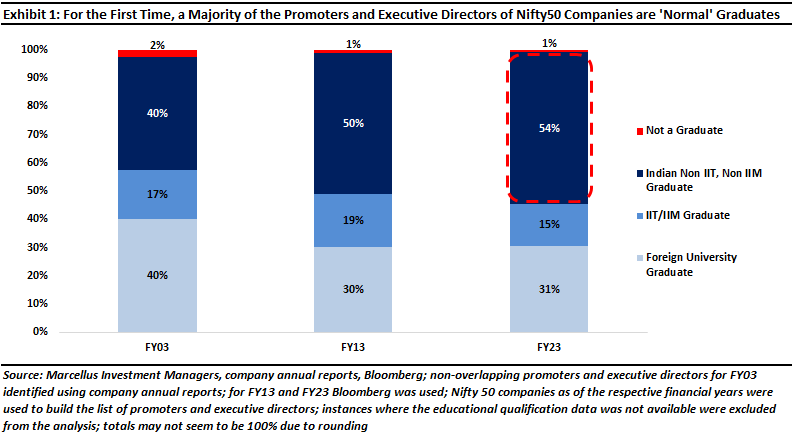

For the first time in India’s history, a majority of the promoters and executive directors of Nifty50 companies are NEITHER foreign educated NOR educated at the elite IITs & IIMs. Instead, majority of the people running Nifty50 companies now have ‘normal’ Indian degrees. Symptomatic of this transformation is HDFC Bank, India’s second largest listed company by market cap. All the Executive Directors on the Board of the bank are graduates of Mumbai University and the rise of such executives is now the norm in India. The old conglomerates run by elite families – whose core strengths were Anglicized ways & political connectivity – are steadily fading away. Entrepreneurial drive, the aptitude to understand and use tech and the ability to harness diverse talent pools are now crucial for success in modern India. India’s most successful companies – including the constituents of our portfolios – symbolize this change of guard.

Rapid economic growth changes lots of things

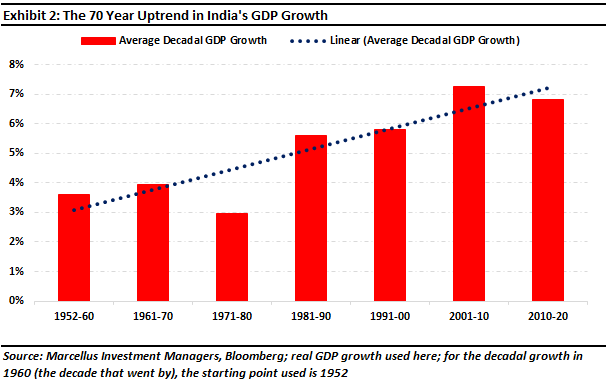

India’s economy grew at an average 5.6% per annum through the 1980s, 5.8% p.a. through the 1990s and it has grown at an average of 6.6% p.a. in this century. Rapid economic growth has created both, a pressing need for talent, and massive opportunities. This has resulted in the democratization of opportunities in modern India as, Shekhar Gupta, explained in a recent article:

“As long as the economy was small and growing slowly, the few privileged institutions sufficed to produce the talent India needed, from corporate boardrooms to the civil services and the judiciary. Now, a rapidly growing economy needed many more talented people and a much larger catchment area. St. Stephen’s/Doon/Mayo/St. Columba’s/St. Xavier’s/La Martinière… are still great institutions — they may be India’s finest even now — but they are just too few to meet India’s need for talent.

That’s why a Tata Administrative Services equivalent today needs to go way beyond these institutions, family networks and checking the names of the candidates’ fathers. The desperate, slog 24×7 push of middle, lower middle and poor India, meanwhile, has made it much, much more competitive to crack the UPSC examinations. Track the lists of toppers and rank-holders published by IAS academies when you open our full front pages now, and check if there are any from these old institutions. It is just too hard to compete, and even in the interview process, there is no premium on pedigree.” – Source: The Print, see https://theprint.in/national-

The fading away of an old, established elite – the inheritors of the British Raj so to speak – has taken place over the past four decades. In its place has emerged a new elite which hails from more modest economic backgrounds, speaks English with a vernacular accent, is at ease with using technology and is confident of its ability to manage diverse pools of talent. How did this transition take place? India’s history suggests that there were four distinct eras in this remarkable journey.

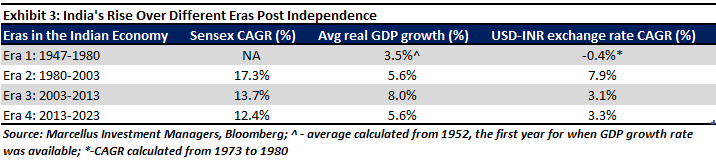

Era 1: 1947 – 1980 – Wars, famines & socialism

“There were no longer any rules, and India – so often invaded, conquered, plundered, with a quarter of its population always in the serfdom of untouchability, people without a country, only with masters – was discovering again that it was cruel and horribly violent.” – VS Naipaul in ‘India: A Wounded Civilization’ (1977)

In a dirt-poor nation (repeatedly ravaged by famine, food shortages and wars with neighbors), capital scarcity was endemic in the decades immediately following Independence. Access to capital and access to the new political elite (who controlled the ‘License Raj’) in the state capitals and in New Delhi was essential for success post-1947. Only two constituencies were able to pull this off:

- Giant Public Sector Units that the successive socialist Governments – heavily influenced by the perceived success of Communism in the USSR – chose to cultivate and capitalize on (e.g., State Bank of India, Steel Authority of India, Coal India, Bharat Heavy Electricals Ltd). Many of these firms were actually private sector entities which the Government of India nationalized by fiat e.g., State Bank of India and Coal India.

- Family run conglomerates which had already attained scale, wealth, and success in the pre-Independence era e.g., Tatas, Birlas, M&M, Godrej, and TVS.

For pretty much everybody else, the first three decades after Independence was a really difficult time. The discontent within India found its expression through the medium of cinema with the 1970s seeing the rise of the ‘Angry Young Man’. Amitabh Bachchan became a superstar by capturing the face of how Indians ought to deal with this disillusionment with Zanjeer in 1973 and Deewar in 1975 being blockbusters.

Era 2: 1980 – 2003 – Independent India’s first brush with capitalism

“…India was, in the simplest way, on the move, that all over the vast country men and women had moved out of the cramped ways and expectations of their parents and grandparents and were expecting more.” – VS Naipaul in ‘India: A Million Mutinies Now’ (1989)

The first chinks of light came in the early 1980s as the then Prime Minister (PM), Indira Gandhi, started liberalizing the Indian economy. From 1980 onwards, India’s GDP growth per capita doubled from the miserable 1.7% rate the country had clocked between 1947-80. What was responsible for this upshift in GDP growth? In a celebrated paper published in 2004, Dani Rodrik and Arvind Subramanian say:

“…the trigger for India’s economic growth was an attitudinal shift on the part of the national government in 1980 in favor of private business. The rhetoric of the reigning Congress Party until that time had been all about socialism and pro-poor policies. When Indira Gandhi returned to power in 1980, she re-aligned herself politically with the organized private sector and dropped her previous rhetoric. The national government’s attitude towards business went from being outright hostile to supportive. Indira’s switch was further reinforced, in a more explicit manner, by Rajiv Gandhi following his rise to power in 1984. This, in our view, was the key change that unleashed the animal spirits of the Indian private sector in the early 1980s….

A pro-business orientation, on the other hand, is one that focuses on raising the profitability of the established industrial and commercial establishments. It tends to favor incumbents and producers. Easing restrictions on capacity expansion for incumbents, removing price controls, and reducing corporate taxes (all of which took place during the 1980s) are examples of pro-business policies, while trade liberalization (which did not take place in any significant form until the 1990s) is the archetypal market-oriented policy…” (Source: https://www.imf.org/external/

This doubling in economic growth first in the 1980s and then another doubling in the 1990s (on the back of an epic second wave of economic reforms catalyzed by the then PM Narasimha Rao and Finance Minister (FM) Manmohan Singh) unleashed the first wave of entrepreneurial activity in Independent India.

Two different types of entrepreneurs emerged over this remarkable 20-year period:

- Larger-than-life entrepreneurs like Karsanbhai Patel (Nirma), Dhirubhai Ambani (Reliance), the Ruias (Essar), the Dhoots (Videocon), the Jindals (Jindal Steel) and the Hindujas (Ashok Leyland, IndusInd Bank, Gulf Oil) built pan-India scale & muscle over this 20-year period. They were financed primarily by public sector banks over this period with domestic capital markets playing second fiddle. Private sector banks did NOT have meaningful financing capacity in this stage of India’s economic evolution. Access to polity remained critical for success as licenses, permissions, permits aplenty were still required. However, the new gen entrepreneurs were able to muscle into the corridors of power that mattered and get relevant access.

- Technocratic entrepreneurs educated either in India’s elite institutes of higher education (the IITs, IIMs, BITS, IISc, NCL) or educated abroad emerged and scaled up large businesses e.g., Deepak Parekh (HDFC), Narayana Murthy (Infosys), Ratan Tata (Tata group), Yusuf Hamied (Cipla), Anji Reddy (Dr Reddy’s), and Desh Bandhu Gupta (Lupin).

Whilst the old, established elites faced a challenge to establish their grip on the keys to the kingdom of wealth, their way of life (i.e., speaking BBC English, cultivating the ways of the West) was what everyone else aspired to. Symptomatic of this yearning for credibility in the eyes of the West is entrepreneur Kashyap Deorah’s description of his fellow IIT (Mumbai) students’ mindset in the closing decade of the previous century:

“We were blazing the trail for IIT Bombay to become another Stanford University and Powai to become another Silicon Valley. We were building a global company out of India when the only tech business that India was known for was IT services and outsourcing. We had raised equity capital when there were no venture capitalists investing in early-stage tech start-ups in India. We were starting a movement by staying back in India when everyone in our batch left for the US and those who stayed were the ones who could not go…” [Source: ‘The Golden Tap’ by Kashyap Deorah (2015)]

Poverty, relative to the West, was still triggering an inferiority complex in the Indian mind. For that to change, we needed the onset of the 21st century.

Era 3: 2003 – 2013 – The rise of, both, crony capitalists and technocrats

Once we entered the 21st century’s first bull market from 2003-08, Indian capitalism’s wild side was unleashed. Now the public sector enterprises and the old school conglomerates started giving way rapidly to:

- The crony capitalistic companies which mushroomed in sectors where the polity-controlled access to licenses, permissions and contracts were required e.g., real estate, construction, power generation and distribution, metals & mining, and telecom.

- High quality private sector enterprises run by clean, competent and driven management teams. Amongst the most successful listed private sector firms from this era (as measured by market cap change in absolute terms from 2003-13) were HDFC Bank, HDFC, Infosys, and ITC.

Financed by Foreign Institutional Investors, private sector banks, and by copious amounts of Private Equity (PE), the aspirations of the Indian entrepreneur now changed. Owning private jets, IPL cricket teams, mansions in London, subsidiary companies in the West and entire ministries in the government became important status symbols for the men who now mattered in India.

The climax of this wild phase of capitalism was 2010-2011, years in which the then Comptroller & Auditor General of India (CAG), Vinod Rai, laid bare the corruption plaguing the country in a series of hard-hitting reports. The CAG’s reports showed how the nexus between politicians and crony capitalists was being used to purloin public assets for private profit (see more here).

Whilst the outsized corruption of this era was a big negative, the discrediting of the established way of doing things e.g., practicing champagne socialism in the elite clubs of Bombay and Delhi whilst speaking Anglicized English was the lasting legacy of this era. Indians’ attitude towards the government, towards business, and to its politicians changed decisively in this era. A certain way of living, behaving and thinking lost credibility in the corridors of power in India. As the Financial Times’ then South Asia bureau chief, Edward Luce, said in his 2006 book, ‘In Spite of the Gods: The Strange Rise of Modern India’: “The employment of hundreds of thousands of young engineers, scientists, economics and English graduates on pay scales that often exceeded those of their parents nearing retirement age created a new generation of consumers with little time for India’s traditional pace of life.”

Era 4: 2013 – 2023 – A new breed of entrepreneur takes center stage

“Networking inherently implies equality. Everyone, rich and poor, is plugged into the same electric, water, sewer, gas and telephone network. The poor may only be able to hook up years after the rich, but eventually they receive the same access.” – Robert Gordon in ‘The Rise & Fall of Economic Growth’ (2016).

Leaving aside the NDA’s victories in the General Elections of 2014 and 2019 which led to the broader policy changes that the country witnessed, three other sets of factors have kicked-into play over the past decade:

- India has got networked. The national highway network saw a near doubling from ~79K km in 2012 to ~140K km in 2022, domestic air travel passengers more than trebling from ~54 mn in 2009 to ~170 mn in 2019 (pre pandemic), households with broadband connections grew ~7x from ~20 mn in 2013 to ~137 mn in 2023, the number of bank accounts grew ~3x from ~100 crores in 2015 to ~300 crores in 2023.

- The India stack was built. It began with Aadhaar (UIDAI or Unique Identification Authority of India) in 2009 which gave a digital identity to all the citizens of the country. This was followed by Jan Dhan bank accounts introduced in 2014 which successfully gave every Indian family a bank account. This combined with the proliferation of mobile phones in India and the launch of Jio’s ultra cheap mobile broadband services in 2017 networked India digitally. This in turn paved the way for the creation Unified Payments Interface (UPI), where anyone with a bank account, a smartphone with an internet connection can transfer any amount of money to anyone in the country instantly! Today, more than 9 bn UPI transactions are taking place each month and over half of India’s GDP is being transacted via UPI (see our blog dated September 2022 From Aadhaar to ONDC: India’s Methodical Build of Digital Assets Creates Competitive Advantages)

- The cost of capital dropped sharply measured not just by the 10 year-Government of India bond yield (which has dropped from ~9% in Aug ’13 to ~7% now) but also by the large pools of PE and VC money which now flow into India each year [anywhere between $20-70bn depending on what the Federal Reserve is doing with its monetary policy]. Alongside foreign capital, the rapid financialization of savings (e.g., the number of brokerage (Demat) accounts has grown 8x over the past decade) drove a structural downtrend in the cost of both debt and equity capital.

Investment implications

As new entrepreneurs from smaller towns – particularly those with a strong grip on how modern tech works – are pushing the entrenched elites of the big cities out of the way. We are seeing rapid changes in India’s Boardrooms. No longer are people with crisp English, membership of the right clubs and degrees from prestigious universities assured a place at the apex of India’s economic pyramid. The new elite are those with a strong grip on vernacular languages, a practical understanding of how small-town India functions.

Venture capitalist Rahul Chandra describes his first meeting around 15 years ago with exactly this kind of entrepreneur, Vijay Shekhar Sharma (the founder of Paytm):

“Unlike the typical mould of savvy entrepreneurs who pitched to us, Vijay did not have an Ivy League or multinational corporation background. He was a small – town guy, like me but the similarity ended there. I had gone to a Jesuit school where the emphasis on speaking proper English had been drilled into my head. Vijay was speaking in a curious Hinglish. He punctuated every sentence with an ‘okay’. But damn, he had some energy. I could tell that sitting down was too passive for him. Given a chance, he would stand up and walk all over the room while explaining himself. His hands had a life of their own. As he moved them, the vision of Vijay Shekhar Sharma started getting painted in my head….

Within an hour, this thirty – two – year – old from Aligarh had not only floored a room full of VCs , but also generated some fondness for his classic David – versus – Goliath persona …. in Vijay , we saw the promise of a new generation of entrepreneurs who were breaking the traditional mould . They didn’t come with a background in the space they wanted to disrupt . They didn’t come from posh schools or carry MBA degrees. They spoke ‘Indian’ and knew what it took to build Indian companies with desi sensibilities.” [Source: The Moonshot Game by Rahul Chandra]

A combination of these factors (networking, India stack, drop in cost of capital) has unleashed long pent-up entrepreneurial energy not just in the tech & start-up space (resulting in the creation of 68 Unicorns) which were primarily financed by foreign PE & VC capital but also in conventional businesses (i.e., businesses whose founders were either part of the old elite or the technocrats who got educated at premier institutions in the country, and were primarily financed by the Indian stock market) like:

- Bajaj Finance (~50x share price growth in the last 10 years): According to market research, consumer durable financing penetration (share of consumer durables getting financed as % of sales) has increased from high single digits to 30-40% in the last decade. In India – where the common people’s aspirations are greater than their ability to pay – innovations like zero cost monthly installments (with subvention through the manufacturer) along with increased formalization (organized retail stores reaching smaller towns) and intelligent use of technology by lenders has led to a revolution in consumer durable financing industry. Bajaj Finance (BAF) has been at the forefront of this revolution benefiting. BAF positioned itself to benefit from the growing wallet size of the middle class and moved from a transactional relationship to a 360-degree relationship betting on higher velocity of loans, and thereby systematically planned new product launches and geographic additions. The trinity of structural changes referenced above has facilitated convenient purchase of consumer durables from stores within minutes. BAF’s heavy investments in data analytics (the firm is the largest user of Salesforce in Asia) has allowed it to fine tune availability of products whilst managing risk metrics at an unmatched scale. BAF’s Earnings Per Share (EPS) has grown 16x in the last decade.

- Astral (~40x share price growth in the last 10 years): Astral has implemented tech both in its distribution system and in its supply chain and benefited immensely from the same. It implemented a Distribution Management System (DMS) in 2019 which enabled its distributors to better plan their purchases, manage inventory, place orders online, etc. Astral also launched a loyalty program in 2019-20 for its channel partners, through which its distributors, dealers, as well as plumbers/carpenters were rewarded for their purchases. The firm launched a mobile app through which influencers like plumbers or carpenters were able to receive reward points (to the tune of 1-2% of purchase value). They were also encouraged to scan QR codes printed on the drum of adhesives or package of pipes following which they received rewards in their bank accounts. Astral provides ‘channel financing’ to its distributors (partnering with banks) to provide them access to funding at lower costs and improve the velocity of their working capital. The combined result of these efforts is 28x growth in Astral’s Free Cashflows over the past decade.

- Divis Laboratories (~6x share price growth in the last 10 years): Divi’s Laboratories business is mainly involved in manufacturing and selling of Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs), primarily for the exports markets. Whilst India was part of the WTO TRIPS (Trade Related Intellectual Property Rights) Agreement, patent laws in India were not in line with what other countries were following. In 2004, however, India amended the Patents Act and included pharmaceutical and agrochemical products under it. This helped Divis get more business from overseas pharma majors for manufacturing pharmaceutical APIs exclusively on their behalf by ensuring utmost protection of their Intellectual Property (IP). This outsourced manufacturing business accounts for almost one half of the company’s business currently. Additionally, India’s improved logistical infrastructure has helped the company reduce its average inventory days by 25% from ~160 days in FY11 to ~120 days now. Divis Labs’ EPS has grown more than 3x over the past decade.

- Eicher Motors (~12x share price growth in the last 10 years): A second derivative of a more networked economy and greater banking penetration has been increased disposable income levels for the Indian middle class. This has driven premiumization of consumption in India. Eicher Motors, with its Royal Enfield brand, was quick to tap this opportunity and pioneered in the premium motorcycle market in India by launching its famous ‘Classic 350’ motorcycle in 2009. Thereafter, Eicher Motors cemented its initial success by swiftly expanding its distribution network from 250 dealer points in FY12 to 2000+ dealer points in FY23. Simultaneously, it launched various new models in the premium segment over the last 10 years, viz. Bullet 350, Himalayan, Meteor 350, etc. Consequently, from FY13 to FY23, Royal Enfield’s sales have grown 6x from 122,000 units in FY13 to 734,000 units in FY23 in the domestic market. Additionally, a drop in cost of funds has also led to an increase in financing penetration. 10 years ago, only 30% of Royal Enfield motorcycles were getting financed, whereas now, more than 55% of Royal Enfield motorcycles are getting financed. Eicher’s EPS has grown 3x over the past decade.

The old elite were in a way the remnants of the British Raj. The new elite are a more indigenous proposition. That in itself implies impending economic & social churn. In practical terms that means that we at Marcellus, and especially our small-midcap teams, will have our work cut out as we hunt for the next generation of Bajaj Finance, Astral Poly and Divis Labs.

Nandita Rajhansa and Saurabh Mukherjea work for Marcellus Investment Managers (www.marcellus.in). Amongst the companies mentioned in this note, HDFC Bank, Bajaj Finance, Astral, Divi’s Laboratories, Eicher Motors and Infosys are part of Marcellus’ portfolios. Nandita and Saurabh may be invested in these companies and their immediate relatives may also have stakes in the described securities.

If you want to read our other published material, please visit https://marcellus.in/blog/

Note: the above material is neither investment research, nor investment advice. Marcellus does not seek payment for or business from this material/email in any shape or form. Marcellus Investment Managers Private Limited (“Marcellus”) is regulated by the Securities and Exchange Board of India (“SEBI”) as a provider of Portfolio Management Services. Marcellus is also a US Securities & Exchange Commission (“US SEC”) registered Investment Advisor. No content of this publication including the performance related information is verified by SEBI or US SEC. If any recipient or reader of this material is based outside India and USA, please note that Marcellus may not be regulated in such jurisdiction and this material is not a solicitation to use Marcellus’s services. This communication is confidential and privileged and is directed to and for the use of the addressee only. The recipient, if not the addressee, should not use this material if erroneously received, and access and use of this material in any manner by anyone other than the addressee is unauthorized. If you are not the intended recipient, please notify the sender by return email and immediately destroy all copies of this message and any attachments and delete it from your computer system, permanently. No liability whatsoever is assumed by Marcellus as a result of the recipient or any other person relying upon the opinion unless otherwise agreed in writing. The recipient acknowledges that Marcellus may be unable to exercise control or ensure or guarantee the integrity of the text of the material/email message and the text is not warranted as to its completeness and accuracy. The material, names and branding of the investment style do not provide any impression or a claim that these products/strategies achieve the respective objectives. Further, past performance is not indicative of future results. Marcellus and/or its associates, the authors of this material (including their relatives) may have financial interest by way of investments in the companies covered in this material. Marcellus does not receive compensation from the companies for their coverage in this material. Marcellus does not provide any market making service to any company covered in this material. In the past 12 months, Marcellus and its associates have never i) managed or co-managed any public offering of securities; ii) have not offered investment banking or merchant banking or brokerage services; or iii) have received any compensation or other benefits from the company or third party in connection with this coverage. Authors of this material have never served the companies in a capacity of a director, officer or an employee.

This material may contain confidential or proprietary information and user shall take prior written consent from Marcellus before any reproduction in any form.