OVERVIEW

India’s savings rate, on a net basis (i.e., savings less borrowings), has touched a 40-year low, as for the first time ever, Indian households are borrowing more than they are saving through bank deposits. This fall in the net savings rate is a by-product of three structural trends: (a) the youthful demography of the nation; (b) the strong employment prospects of creditworthy Indians working in the knowledge economy; and (c) the rise of digitization and the India Stack which is allowing lenders to assess the creditworthiness of hundreds of millions of borrowers who were formerly transacting primarily in cash. Given the underlying drivers of the fall in net savings, it is unlikely that this trend will reverse until economic growth throttles off and unemployment starts rising. When that happens, those who are currently lending abundantly will face their day of reckoning.

“Credit offtake in India has been unbelievable…have been doing this for 20 years, have not seen the kind of confidence to borrow and consumption on ground ever earlier. Despite RBI’s cautious view on unsecured loans there has not been any slowdown in unsecured credit offtake. RBI has increased scrutiny in unsecured loans, they are asking banks to justify even giving Rs 15 lakh unsecured loans (something like this is unheard of)…and yet end use cases of loans have expanded – a large section is taking loans for lavish weddings, travel, etc (38% of unsecured loans disbursed are with ticket size of Rs 30 lakh+)….Not seeing any signs of slowdown here…we are looking at risk metrics very closely…not seeing any broad-based signs of rising defaults, still pretty healthy. In fact, growth is expected to improve with the festive season upon us….” – COO of one of India’s largest distributors of retail loans.

Should we worry about the surge in household borrowing?

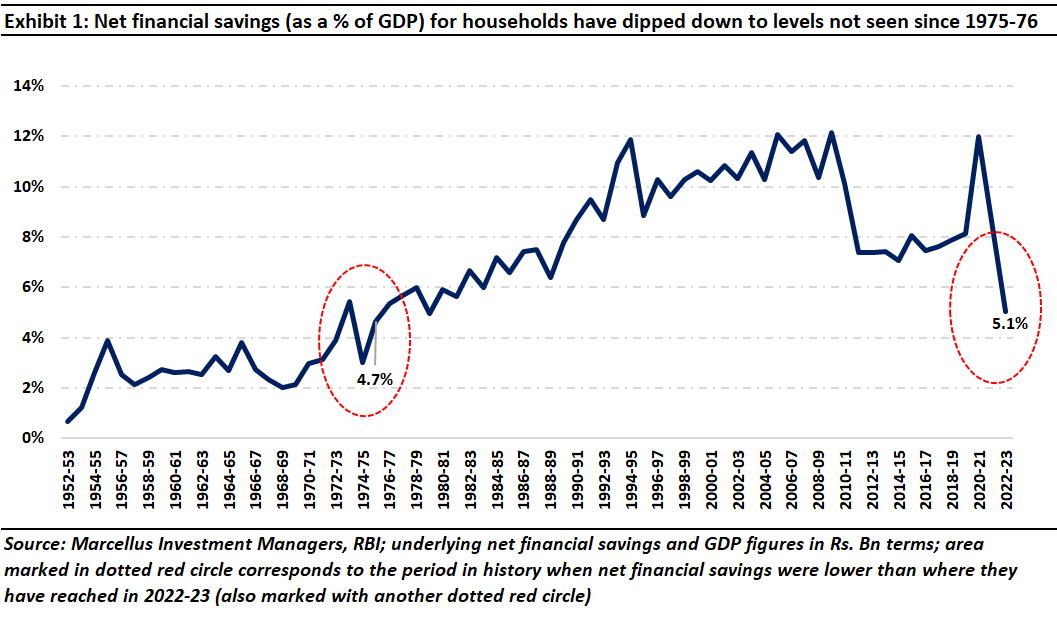

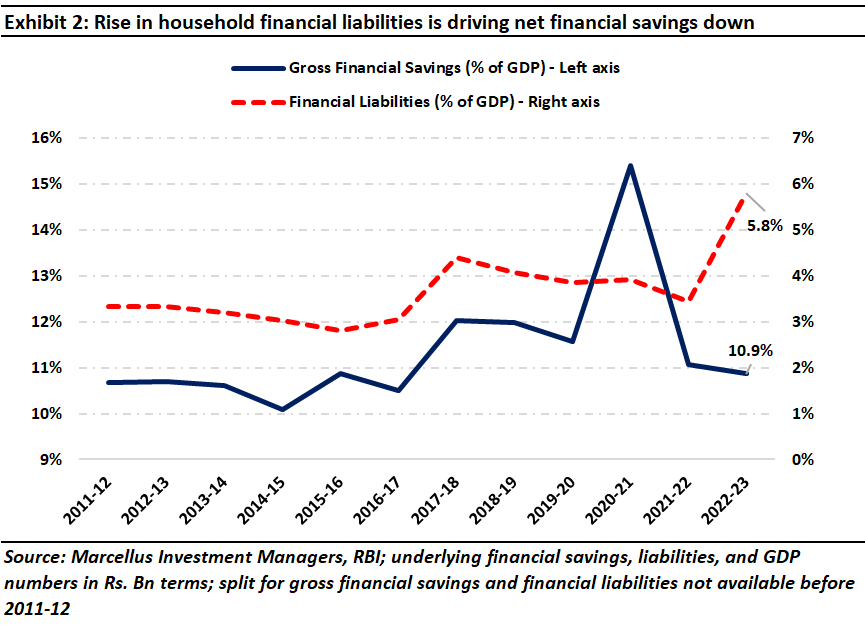

India’s net financial savings (as a percentage of GDP) for households has dipped to 5.1%, a figure that the country had last seen way back in 1975-76 (see exhibit 1). Net financial savings are calculated as gross financial savings less borrowings. If we go one level deeper, an even more interesting picture emerges. Gross financial savings (as a percentage of GDP), after surging unprecedentedly during Covid (in 2021), are now back within their historical band of 10-12%. Financial liabilities on the other hand, have seen a surge post-Covid, causing net financial savings for households to fall (see exhibit 2).

To put this remarkable surge in household borrowing in context, in FY23 households made bank and non-bank deposits of Rs. 11 trillion, but took out loans for Rs. 15.82 trillion i.e., FY23 was the first year when Indian households “crossed the Rubicon and became net borrowers from the financial system” (to use a phrase coined by Aseem Dhru, CEO of SBFC Finance).

Whilst the preceding para focuses on ‘flow’ data (i.e., the amount of household saving & borrowing done in FY23), the ‘stock’ data (or point in time data) is even more startling – at the end of FY23, banks’ personal loans outstanding (made to Indian households) stood at Rs 40 trillion, significantly higher than the Rs 33 trillion the banks have lent to industry. The total stock of household debt as a % of GDP stands at 22% (and of this amount, home loans account for ~50% i.e., the rest of the loans are to finance either short lived assets like consumer durables or vehicles or to finance lifestyle related purchases which have little to no collateral value).

Interestingly, not only is such a low net savings rate unusual in the Indian context (given that India has been accustomed to seeing high net savings rate over the past few decades), but it is also unusual when compared to the East Asian Tiger economies which have financed their high investment rates through high savings rates.

“…East Asia’s success was based on a combination of factors, particularly the high savings rate interacting with high levels of human capital accumulation, in a stable, market-oriented environment—but one with active government intervention—that was conducive to the transfer of technology.” – Joseph Stiglitz, Some Lessons from the East Asian Miracle (J. Stiglitz, 1996)

This begs the question should we as investors in the Indian economy be worried about the dip in India’s net savings rate? More specifically, should we be worried about the surge in household borrowing?

The Life Cycle Hypothesis Model

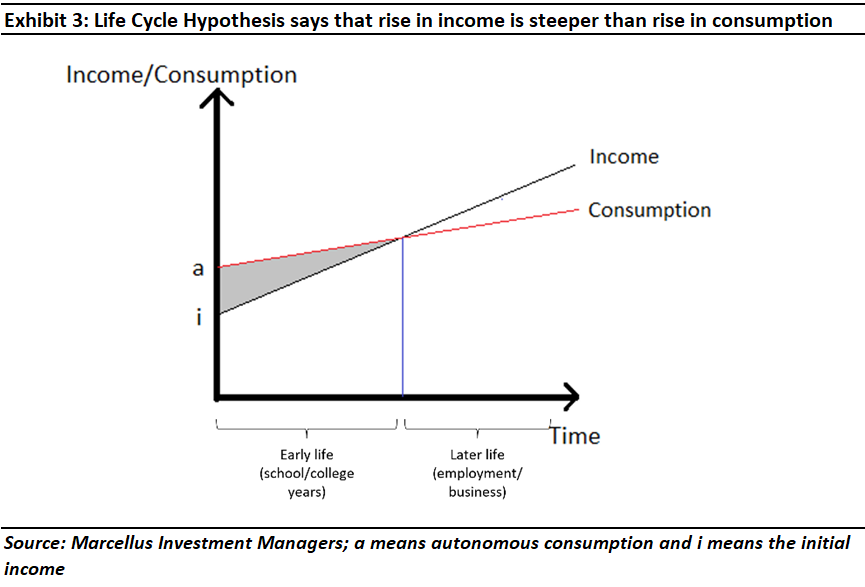

The Life Cycle Hypothesis model was created by Franco Modigliani and his student Richard Brumberg in the early 1950s. As per this model, in the initial years of an individual’s career, there is a natural tendency to borrow because spending on consumption tends to be higher than the – typically meagre – income that an individual receives early in her career. However, as the individual spends more years in employment, her income rises. Then, in the final decades of her career, the individual earns more money than she spends on consumption. These savings are then used to finance her retirement years. If you assume that every individual has this pattern (of borrowing in the opening decades of her career and saving in the closing decades – see chart below), the aggregation of these individual borrowings/savings profiles becomes the country’s aggregate household borrowing/savings.

Now in India’s case, given that the median Indian is 28 years old (and was 25 years old a decade ago), it appears that the majority of Indians are in the opening decade of their careers. Hence, it makes logical sense for them to be borrowing money. Furthermore, as over the past few years, the median Indian has stayed younger, it logically follows that India’s net savings rate has dropped. As and when India begins ageing, we should expect to see the net savings rate improve. The logical culmination of this journey several decades hence would be a country like Japan with an aged population and very high savings rates (~30% of GDP).

A booming economy with jobs aplenty

Not only is India’s overall economy in good shape (latest GDP growth print for Q1 FY24 was 7.8%), but the country’s Services sector is also going through a purple patch. PMI for the Services sector is rising at the fastest rate in the last 13 years (source: Economic Times) and the prospects for employment especially in the formal sector look bright. In fact, as knowledge and technology intensive manufacturing companies increasingly shift away from China and towards India (see our blog dated 24th November 2022, China’s Unravelling Creates a US$300 Billion Opportunity for India), the requirement for skilled personnel is only going to rise.

In fact, even before China+1 has fully begun playing out, we can see a super charged job market in India where unemployment rate has fallen to 6.6% in April-June 2023 quarter according to the Periodic Labor Force Survey (or PLFS) (source: Moneycontrol).

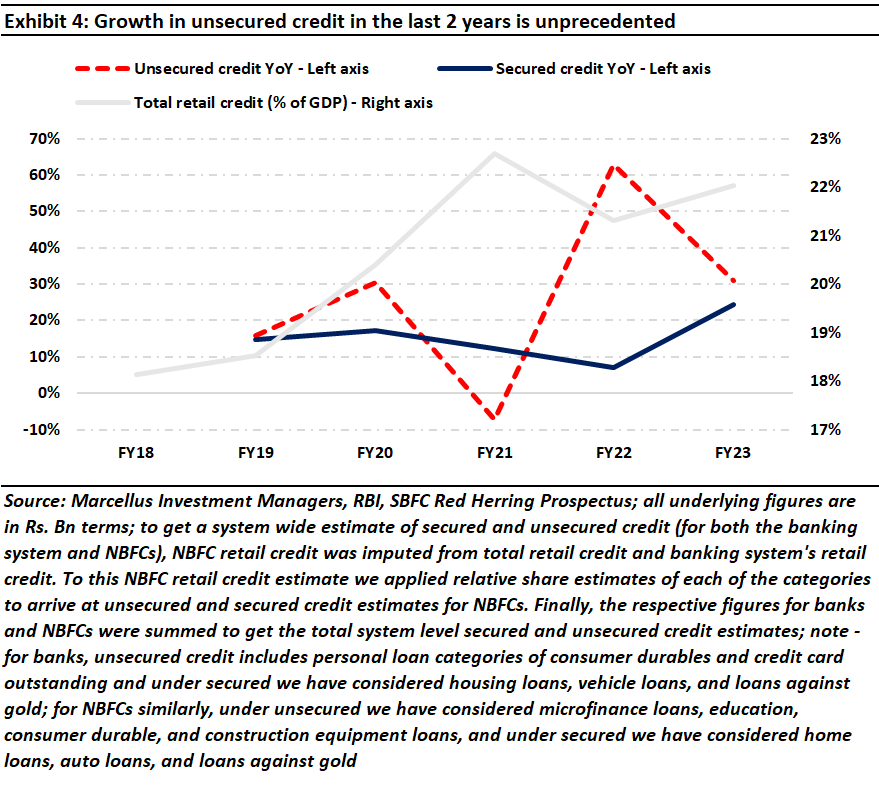

As a result, most people who are a part of India’s Services economy and the broader knowledge economy (including sectors like Pharma, Electronics, Engineering, etc.) have strong visibility on their future earnings. This could be resulting in them financing current consumption not just with current income but also with personal loans from banks, which have grown at 17% on an absolute basis from March to August 2023, and have grown at 28% p.a. since 1st September 2021 (basically, since the end of Covid-19). Personal loans by both banks and NBFCs (i.e., secured plus unsecured loans taken by households) as a % of GDP stand at 22% (as of March 2023), the highest since 2018 (from when the data for NBFCs is available).

Rise of the India stack and greater financial visibility

13 years ago, the revolutionary idea of giving each Indian an identity number, akin to a social security number, was implemented. Over the years, using Aadhaar as a bedrock, and then linking that first to bank accounts and then to mobile phone numbers created the foundation of what is known as the ‘India Stack’. This Stack has led to an overhaul of how much of the Indian economy functions.

As explained in our note on the digitization of the Indian economy (From Aadhaar to ONDC: India’s Methodical Build of Digital Assets Creates Competitive Advantages, 2022), “Over the past decade the Indian economy – fragmented into several regional economies a decade ago – has gradually been integrated by the doubling of highway networks, tripling of local airline traffic, the introduction of GST and – most importantly – rapid digitization of the economy. From Aadhaar (in 2010) to UPI (in 2016) and now on to ONDC (Open Network for Digital Commerce) – India is gradually building a digital economy which will ultimately give the country a global competitive advantage in how money and goods move around the country.”

In the same note we explained why UPI (Unified Payments Interface) is such a breakthrough construct for India accounting as it does now for transactions worth almost 50% of India’s GDP: “The creation of JAM in 2015 paved the way for UPI (Unified Payments Interface) in 2016. UPI is a real-time payment system wherein a user can instantaneously transfer funds to someone using any bank account that they hold and is registered on the UPI app on a smartphone. Furthermore, there are multiple apps which offer this service, but the transactions are not app-dependent, meaning a user with one UPI app can send money to another user who has an account on another UPI app seamlessly, thus making the system truly interoperable. UPI was developed by National Payments Corporation of India (NPCI) and is regulated by the RBI.”

The advent of UPI means that banks can see real-time every single financial transaction that an account holder is making. The accumulation of this data gives the banks far greater granularity on their customers’ financial activities and hence their credit profile. Moreover, individuals who weren’t under the purview of the banking system five years ago because they were transacting in cash, the formalization of transactions (i.e., the transactions are now happening inside the ambit of the banking system) means that they have now become creditworthy. Many of these recent cohort of creditworthy customers are youngsters who – as explained using the Life Cycle Hypothesis – should be borrowing to finance their consumption needs.

And this is indeed what is happening – as per our primary data checks in large and small consumer durable/electronic stores in Mumbai, most people (around 80%) are buying products utilizing either their credit cards or financing options offered by the likes of Bajaj Finance or HDFC Bank. Having visited multiple electronics stores in Mumbai, we can see that credit card is the preferred mode of transaction for purchase (due to the offers and/or benefits offered by credit card issuers) for consumers. However, for smaller ticket items (i.e., items that cost less than Rs. 20-30K), consumers prefer taking a low or zero cost financing option.

The reason for this preference is quite straightforward: the process of borrowing money to finance a consumer durable is fast – it takes a Bajaj Finance representative in the store no more than 5 minutes to give the customer a lending decision once the customer has supplied the following details: PAN, address proof, and income proof. Bajaj Finance’s algorithms in turn are able to make the lending decision in 5 minutes because of the wealth of customer-specific data stored in the firm’s vast data lakes. Thanks to this seamless and hassle-free experience along with the ability to get the loan at minimal cost, most consumers in this category prefer using a financing option rather than paying upfront.

The company which has understood this dynamic better than almost any other is Bajaj Finance, a firm whose loan book, profits, and share price has compounded at 31%, 35%, and 47% p.a. respectively over the past decade.

According to the Chief Risk Officer of one of Bajaj Finance’s rivals, “This is a business, where availability of large sums of data is the biggest advantage. When this business was scaled, Bajaj Finance had access to customer data of ~200 mn customer where they had done consumer durable financing and another ~200 mn of the Bajaj group (i.e., their general insurance and life insurance subsidiaries). customers. Given the availability of this large data base, attractive offers could be made to the customers. This business has been built over various rounds of testing; certain unique underwriting parameters have been run on unique customer pools which have rich underwriting experience. Bajaj Finance invested a lot in the data analytics team. The team has hunger for data – if one gives them data on customers – the team’s ability to come up with unique underwriting models is unparalleled.”

Investment Implications

As explained above, the recent dip in India’s net savings rate is a by-product of multiple structural trends: (a) the youthful demography of the nation; (b) the strong employment prospects of creditworthy Indians working in the knowledge economy; and (c) the rise of digitization and the India Stack which is allowing lenders to assess the creditworthiness of hundreds of millions of borrowers who were formerly transacting primarily in cash.

Given the structural underpinnings of the fall in the net savings rate, it is unlikely that this trend will reverse unless there is a marked drop in the GDP growth and a rise in unemployment. What smart lenders are doing is – without waiting for the bad news on the economy to emerge – they are already turning off the tap on the frothiest segment of borrowing, namely, unsecured borrowing.

Why is this significant? Whilst the economy as a whole is in good shape, one segment that poses a significant risk to lenders is unsecured lending. There are three reasons why investors should worry about small ticket unsecured lending:

- Stacking of loans by consumers: Anecdotally, we’ve been hearing about the explosive increase in the risk appetite of consumers for some time now. Recently, there’s empirical evidence emerging on this trend as well. According to a report published by UBS in October 2023, the share of outstanding personal loans to borrowers with five or more existing personal loans has gone up from being about 1% in FY18 to 7.7% in FY23. What this essentially means is that people are taking multiple loans, even when they are already servicing previous debts.

- Small ticket size could have large ramifications: From our visits to especially smaller consumer durable stores, we understand that the option to finance purchases has been predominantly used by consumers buying items that cost less than Rs. 20K. In fact, the popularity of this method of payment is so high that one salesperson at a small electronics store in Mumbai told us that around 95% of his customers availed one of the financing options available at his store for items priced as low as Rs. 10,000.

- Delinquency rates are already shooting up: As reported by Reuters (using data from credit bureau CRIF Highmark), delinquencies for loans under Rs. 50K were at 8.1% as of June 2023, well above the 1.4% bad loans ratio for all retail loans as of March 2023. The same Reuters article said, “The total value of loans below 10,000 rupees grew 37% in the financial year ending March 31, 2023, while loans of 10,000-50,000 rupees rose 48%, according to CRIF data.”

In such a situation, what sets high quality lenders apart is the willingness to throttle off on lending several quarters before other lenders have woken up to the altered realities. There aren’t too many lenders that exemplify this as much as Bajaj Finance and HDFC Bank do.

Bajaj Finance in its Q2 FY24 results said that it has cut 8-14% of its low-ticket unsecured lending business across products owing to concerns of over leverage amongst these customers and imprudent behavior on the part of these borrowers. Notably, before the Q2 FY24 results, Bajaj Finance announced a fundraise of Rs 100 billion of fresh equity capital [Cholamandalam Investment & Finance, another Marcellus investee company, also raised Rs. 40 billion in September 2023].

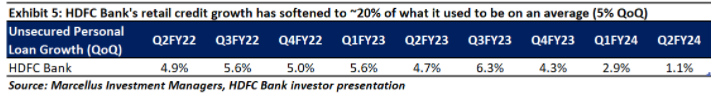

HDFC Bank’s Q2 FY24 results showed it has pulled back on unsecured loans as well. In Q3 FY23, HDFC Banks unsecured book grew 6.3% QoQ. In the latest quarter, the corresponding growth rate is down to 1.1% (see table below).

And that’s the way of the world – the grown-up lenders with the strongest risk management systems throttle off from partying and strengthen their balance sheets a few quarters before everyone else. Then when the party ends and the weaker lenders blow-up, the grown-ups clean-up market share and become better than ever. This is the third time in 15 years we are watching the same story play out in India and it’s unlikely to be the last time that we will choose to ride the cycle with the strongest and smartest lenders in the country.

Nandita Rajhansa and Saurabh Mukherjea work for Marcellus Investment Managers (www.marcellus.in). We thank Keshav Binani and Tej Shah for their invaluable inputs. Amongst the companies mentioned in this note, HDFC Bank, Bajaj Finance, and Cholamandalam Investment and Finance are part of Marcellus’ portfolios. Nandita, Saurabh, Keshav, and Tej may be invested in these companies and their immediate relatives may also have stakes in the described securities.

If you want to read our other published material, please visit https://marcellus.in/blog/

Note: the above material is neither investment research, nor investment advice. Marcellus does not seek payment for or business from this material/email in any shape or form. Marcellus Investment Managers Private Limited (“Marcellus”) is regulated by the Securities and Exchange Board of India (“SEBI”) as a provider of Portfolio Management Services. Marcellus is also a US Securities & Exchange Commission (“US SEC”) registered Investment Advisor. No content of this publication including the performance related information is verified by SEBI or US SEC. If any recipient or reader of this material is based outside India and USA, please note that Marcellus may not be regulated in such jurisdiction and this material is not a solicitation to use Marcellus’s services. This communication is confidential and privileged and is directed to and for the use of the addressee only. The recipient, if not the addressee, should not use this material if erroneously received, and access and use of this material in any manner by anyone other than the addressee is unauthorized. If you are not the intended recipient, please notify the sender by return email and immediately destroy all copies of this message and any attachments and delete it from your computer system, permanently. No liability whatsoever is assumed by Marcellus as a result of the recipient or any other person relying upon the opinion unless otherwise agreed in writing. The recipient acknowledges that Marcellus may be unable to exercise control or ensure or guarantee the integrity of the text of the material/email message and the text is not warranted as to its completeness and accuracy. The material, names and branding of the investment style do not provide any impression or a claim that these products/strategies achieve the respective objectives. Further, past performance is not indicative of future results. Marcellus and/or its associates, the authors of this material (including their relatives) may have financial interest by way of investments in the companies covered in this material. Marcellus does not receive compensation from the companies for their coverage in this material. Marcellus does not provide any market making service to any company covered in this material. In the past 12 months, Marcellus and its associates have never i) managed or co-managed any public offering of securities; ii) have not offered investment banking or merchant banking or brokerage services; or iii) have received any compensation or other benefits from the company or third party in connection with this coverage. Authors of this material have never served the companies in a capacity of a director, officer or an employee.

This material may contain confidential or proprietary information and user shall take prior written consent from Marcellus before any reproduction in any form.