OVERVIEW

Published on: 15 Feb, 2019

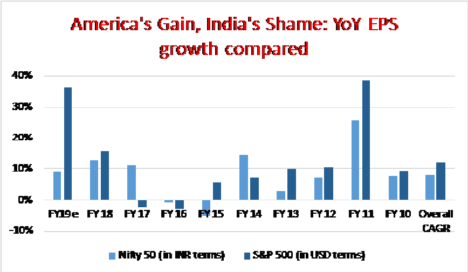

Over the past decade, the Nifty’s earnings have not only grown at a much slower pace than the Indian economy, they have also trailed the S&P500’s earnings growth by a country mile (although the Indian economy is growing much faster than the American economy). This disturbing phenomenon has far reaching implications for Indian investors. –

The Nifty has fallen far behind the Indian economy

Over the last ten years, India’s GDP growth (in nominal terms) has averaged 13% per annum whilst the most popular benchmark index in India, the Nifty, has seen its earnings grow at a mere 8% per annum. In fact, in nine out of the last ten years, the Nifty’s earnings growth has trailed nominal GDP by a country mile (the only exception being FY11). In America on the other hand, nominal GDP growth over the past decade has been barely 4% and yet the S&P 500’s earnings has grown at 12% per annum, a full 400bps faster than the Nifty (even without converting the Nifty’s earnings to US dollars)! Why do the benchmark indices in India and America display completely opposite trends (when compared to the GDP growth of their respective economies) and what implications does that have for investors?

Why does the Nifty lag the Indian economy?

To understand why the Nifty no longer captures the dynamism of the Indian economy a good place to start is the index as it stood ten years ago. On the face of it, the ten year share price return from investing in the Nifty is a very respectable 14% but that is a deceptively flattering figure. A better way to understand the quality (or lack thereof) of the Nifty is to look at the return from investing in the underlying fifty stocks which were in the Nifty ten years ago – such a portfolio (equal weighted) would give you a return of negative 1% per annum (CAGR over ten years). [Note: by starting the measurement in February 2009, when the market was close to its post-Lehman lows, we are giving the Nifty every chance to benefit from an unusually low base.]

If you assume that the cost of equity of a typical investor investing in Indian stocks is 15%, only 18 out of the 50 stocks in the Nifty have given a return above the cost of equity over the past ten years. [This number too is flattered by the fact that our starting period in Feb 2019.] These 18 outperformers – ranked in descending order of performance – are: HCL Tech, TCS, HDFC Bank, Maruti Suzuki, M&M, Zee, HUL, HDFC, Wipro, Tata Motors, BPCL, Infosys, ITC, Siemens, Hindalco, ICICI Bank, Grasim, L&T and Sun Pharma. As you can see from the list, barring four companies, all the other companies are from relatively capital light and/or B2C sectors like Consumer, Auto, Pharma and Banking.

The other 32 companies – whose ten year return is below the cost of capital – are from balance sheet heavy sectors like Power, Construction, Metals, Telecom, Real Estate and Oil & Gas. These sectors accounted for roughly 30-35% of the Indian economy. And yet these companies account for two-thirds of the companies in the Nifty leaving little room in the index for the more vibrant sectors of the economy. The over-representation in the Nifty of the capital heavy sectors of the economy is therefore a key reason its sluggish performance. It is not obvious to us why the Nifty continues to have such a high proportion of companies from balance sheet heavy sectors.

Secondly, over the last five years, the Nifty’s market has increasingly diverged from India’s nominal GDP (after faithfully tracking it for much of the preceding decade). This in turn is suggests that significant drivers of the Indian economy are no longer in the listed market. For example, taxi aggregators (Ola, Uber), online retailers (Flipkart, Amazon), electronics goods manufacturers, car manufacturers other than Maruti, hotels other than Taj, Oberoi and Lemontree, etc – basically most of the things that affluent India buys beyond FMCG and apparel – is no longer in the listed market. These companies are able to access capital at low cost without entering the stockmarket and therefore their contribution to GDP is not reflected in the stockmarket. If, as the Indian economy matures, the unlisted world continues to provide capital at lower cost than the listed market then the gap between GDP and market cap will widen further.

Implications for investor

1. The sluggishness of the Nifty makes its relatively easy for reasonably competent fund managers to outperform the index and unjustifiably claim the presence of skill. Whilst this does pose a challenge for Nifty tracker/index funds (since they are tracking a moribund index), it also opens up enormous opportunities in India for smart beta funds. For example, the Nifty Junior (which represents the 50 most liquid stocks below the Nifty) almost always outperforms the Nifty

2. Given that nearly two-thirds of the Nifty constituents have failed to give a return above the cost of capital, large cap Indian funds which draw their constituents largely from the Nifty are a difficult investment to justify. On the other hand, even a relatively simple method – like our Consistent Compounders algorithm which focuses on a select subset of Nifty stocks – is able to deliver returns which are consistently above the cost of capital.

3. The inability of the Indian stockmarket to provide lower cost funding than the Private Equity (PE) firms is depriving the Indian stockmarket of high quality companies which can dominate their sectors and help the stockmarket participate in India’s economic growth. The more important foreign companies and PE funded companies become in India, the bigger the questions mark around the relevance of the Indian stockmarket as a medium via which ordinary investors can benefit from India’s economic growth.

4. The fact that the S&P500 can consistently grow earnings much faster than US economic growth suggests that American companies can tap into Emerging Markets’ economic growth much better than Indian companies in the Nifty. This not only raises troubling questions about the quality of capital allocation and accounting in many large Indian companies who are in the Nifty, it also suggests that Indian investors should consider investing in a portfolio of global companies who dominate specific segments on a worldwide basis.

If you want to read our other published material, please visit https://marcellus.in/blog/

Saurabh Mukherjea is the author of “The Unusual Billionaires” and “Coffee Can Investing: the Low Risk Route to Stupendous Wealth”.

Note: the above material is neither investment research, nor investment advice. Marcellus does not seek payment for or business from this email in any shape or form. Marcellus Investment Managers is regulated by the Securities and Exchange Board of India as a provider of Portfolio Management Services and as an Investment Advisor.

Copyright © 2018 Marcellus Investment Managers Pvt Ltd, All rights reserved.