OVERVIEW

All happy companies are different: each one earns a monopoly by solving a unique problem. All failed companies are the same: they failed to escape competition – Peter Thiel in ‘Zero to One ‘, (2014)

Peter Thiel in his bestselling book, Zero to One (2014), compared Google with America’s airlines industry. He highlighted that the US airline companies serve millions of passengers and create hundreds of billions of dollars of value each year yet capture an insignificant amount of this value. Compare this with Google, which creates less value but captures far more for itself. Google brought in $50 billion of revenue in 2012 v/s $160 billion for the airline industry, however kept 21% of those revenues as profits – more than 100 times the airline industry’s profit margin that year (and the next year and the one after that). What separates Google from the airline companies is that Google is a near monopoly whereas the airline industry operates in a ‘perfect competition market’.

Where Google can plan for the long-term future and invest in innovation, America’s airline companies are focussed on protecting today’s margins. Thiel suggests that sustainable monopolies can think beyond protecting margins and have the flexibility to care about employees, invest in innovation and build sustainable moats. In contrast, competitive businesses in low margin sectors will pay their workers minimum wages and try to cut corners, sometimes even at the cost of the customer experience. A sustainable monopoly is good not only for its shareholders and its management but also for its employees, customers and business partners.

In a ‘dynamic’ world, evolution of both demand (i.e. customer behaviour) as well as the supply of a product or service can also disrupt some monopolies overnight, the way firms like Kodak and Xerox got disrupted. Therefore, a creative monopolist reinvests the monopoly profits to innovate new products, improve existing products and figure out better ways of meeting the customer’s demand. Hence, progress usually comes from monopolies, and not from ‘perfect competition’.

In ‘Zero to One’ Thiel has also given a framework for new entrepreneurs on how to build a monopoly. First step he suggests is to start small – target a niche market where competitive intensity is very low and the opportunity is being left unaddressed. Next, monopolize the market while building strong barriers to entry and then slowly scale up the business by moving to adjacent or related categories. He suggests a focus on four characteristics of building a monopoly – a) Proprietary technology, b) Network effects, c) Economies of scale, and d) Brand.

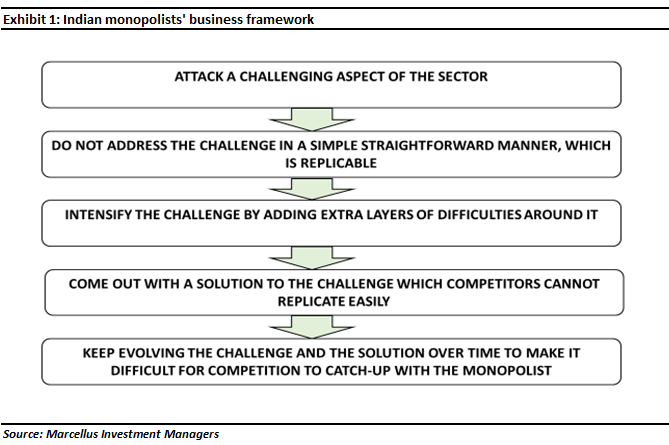

Whilst this framework was given by Thiel in the context of young technology start-ups, in India there exist several monopolies in other large traditional industries as well. The most common framework adopted by Indian monopolists for creating and sustaining a monopoly franchise is given in the flowchart shown above.

Here are a few examples of how dominant franchises in India have implemented this framework in India’s B2C segments:

- The challenge of B2C distribution: In a vast country like India, establishing a distribution network is a challenge because of poor transport infrastructure, and diverse / non-uniform demand across geographies, socio-economic strata of households. Moreover, India has one of the highest number retail touchpoints because even today 90-95% points of sale in most categories consist of mom-and-pop stores across most industries. The simple way to address this challenge is by offering incentives to third party distributors, wholesalers, stockists, etc for executing the hub and spoke distribution. Instead, firms like Asian Paints and Pidilite took the more difficult route to resolve this challenge. Asian Paints removed all layers of channel partners and reached out directly to paint dealers on the high street, while also compressing their channel margins. The incentive offered to these dealers was supply chain efficiencies of (3-4 deliveries per day) which helps these dealers generate a healthy return on their capital employed. This capability was built using tech investments to forecast demand with greater accuracy compared to their competitors. Similarly, Pidilite created a pull-based demand for its products by targeting carpenters (influencers), educating them about the benefits of these products and their application process. Pidilite helped carpenters up-skill themselves through their association with Pidilite. Pidilite followed a similar approach when it launched its waterproofing solution, Dr. Fixit, by setting up the Dr. Fixit institute of waterproofing and training close to 1 lakh applicators annually

- The challenge of retail lending: As a product, bank deposits are largely commoditised. Hence, building a granular retail deposits led liabilities side of the balance sheet is a difficult way to raise funds for a lender. Similarly, building a high quality loan book by selecting borrowers based on their credit scores from a credit rating agency (like CIBIL) is commoditised and can be done by every lender in the industry. However, yields / margins available on such a loan book are wafer thin and hence doesn’t help build a high ROE franchise. One of the simpler solutions to these challenges is to raise funds from the money market (at high rates) and lend to high-risk large corporates at high interest rates. Instead, HDFC bank chose the difficult path – it built the liabilities side of the balance sheet through low-cost CASA (current accounts, savings accounts) and lent largely to high quality retail borrowers at low rates. Similarly, Bajaj Finance solved the asset side problem of a retail lender by leveraging technology to develop credit algorithms to capture datapoints which are not captured in credit scores generated by a credit rating agency and built a huge data-based lending engine to identify the credit worthiness of retail borrowers.

- The challenge of executing brick and mortar retail: Establishing a wide organized retail network is challenging because of some inherent factors like expensive real estate when optimisation of store economics is a challenge given: a) a long and difficult learning curve around optimal store size, location, merchandise layout, etc; b) intense competition from widespread unorganized retail; and c) high attrition in store-level staff which delivers a poor customer interface. In an industry like diagnostic labs, the simple way to build a pan-India business whilst overcoming these challenges is to setup a B2B type of retail network where samples are procured from hospitals or third party labs / collection centres, and reports are white labelled and delivered. Dr. Lal Pathlabs, instead, overcame this challenge in a difficult and slow manner, through significant tech investments and a very gradual geographical expansion of its collection centres and labs. The firm also controls several aspects of the franchisee’s collection centre like layout, supplying some sample collection equipment and in some cases even controlling lab technicians. This has helped the firm optimise store economics and build a highly cash generative business model (unlike most retail businesses which tend to be cash guzzlers).

Investment Implications

It is easy to understand why monopolies are great for their shareholders – high free cash generation (i.e. ROCEs well above cost of capital) and consistent growth in earnings over the longer term tend to result in consistent wealth compounding for shareholders. The high cash generation of monopolies enables them to innovate, strengthen and evolve their competitive advantages. However, spotting the existence of such monopolies is not easy. As Peter Thiel says in his book ‘Zero to One’, “Anyone that has a monopoly will pretend that they’re in incredible competition…. If the monopolists pretend not to have monopolies & the non-monopolists pretend to have monopolies, the apparent difference is very small”. The presence of a business framework along the lines of what is shown in the exhibit above is one of the tools that investors can use to spot the existence of high barriers to entry created by a monopolist around his business.

Marcellus’ investment philosophy revolves around finding dominant companies where this culture of innovation and building new competitive advantages is ingrained in every layer of management because that is what will help them sustain their dominance over long time periods.

Disclosure: Asian Paints, Pidilite, HDFC Bank, Bajaj Finance and Dr. Lal Pathlabs are a part of most of Marcellus’ portfolios.

Deven Kulkarni is an analyst and Rakshit Ranjan is a fund manager at Marcellus Investment Managers