OVERVIEW

The Indian middle class is losing ground not just to the super rich, but also to the poor. Over the past decade, the average annual income for the Indian middle class has stayed flat whereas that for the low-income group has grown at 4% p.a. Three sets of drivers have come together to squeeze the middle class. Squeezed out of the job market by automation & AI, squeezed out of the power ecosystem by newer elites and pushed out of the political system by the rough & tumble of political horse-trading, the Indian middle class is likely to run into further headwinds.

“One of the defining characteristics of the current middle class is its diversity. This diversity acts as a driving factor for different social groups to gain recognition in society through economic progress. However, it also stops it from being a composite unit, which affects its interests at the macro level. This is most evident in politics. A report in the Sunday Guardian notes that ‘since it is politically amorphous, and has not organized itself into a pressure group, even political leaders who have emerged from this segment have not focused on it. As a thumb rule, most of India’s politicians who achieved success either came from the wealthy/dominant classes or conversely the poorest of poor’” – Manisha Pande , Middle Class India: Driving Change in the 21st Century (pp. xxii-xxiii). Kindle Edition.

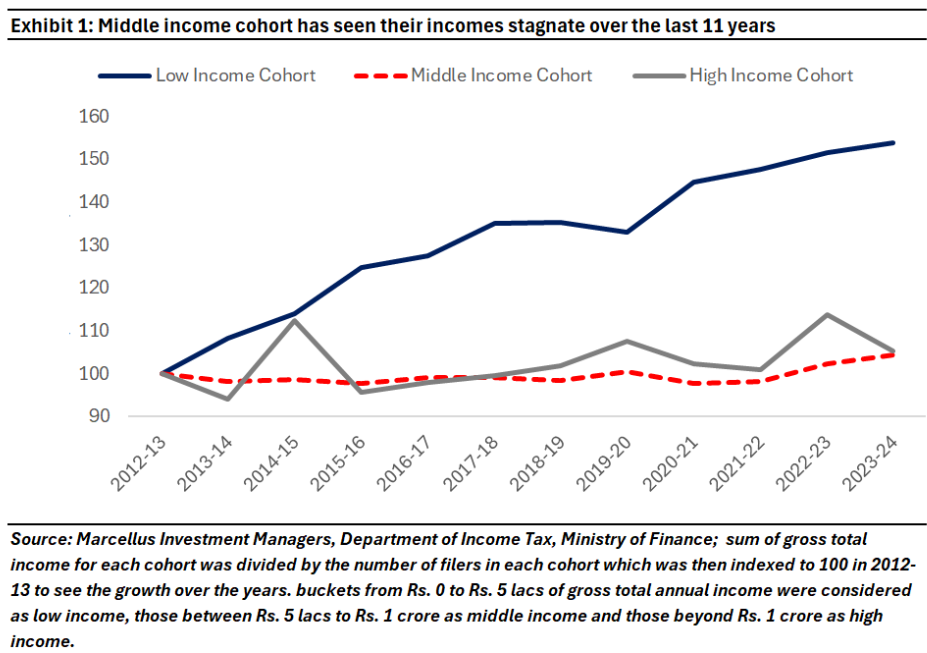

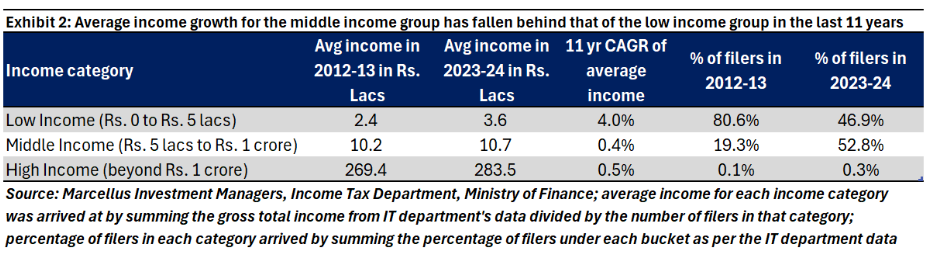

If you define the middle class as those who are financially equidistant between the rich and the poor, then the Income Tax data shows that the Indian middle class is visibly losing ground relative to not just the rich but also relative to the poor.

As can be seen in the exhibit above and in the table below, over the past decade, that 53% of the Indian population that files non-negative tax returns (as of 2023-24) and earns between Rs 5 lacs – 1 crore per annum, has seen its income stagnate (see the dotted red line in exhibit 1). Average annual income for this half of the tax paying population was Rs. 10.23 lacs a decade ago to Rs 10.69 lacs in 2023-24 . This has happened at a time when: a) those earning below Rs 5 lacs per annum have seen their income rise appreciably from an average of Rs. 2.36 lacs to Rs. 3.63 lacs; and b) those earning above Rs 1 cr per annum have seen their income inch up from Rs. 2.69 crores to Rs. 2.83 crores on an average. The penultimate columns of the exhibit below clearly show that: (a) a substantial number of filers have moved from low income cohort from 2012-13 to middle income cohort in 2023-24 (b) their incomes, however, have not risen at the same pace as their entry into the cohort )c) the movement from the middle income to high income cohort has not been material either in the last 10 years [implying that a large chunk of the population is still within the middle income cohort whose incomes on an average haven’t grown in this period].

So, why is the Indian middle class getting squeezed so comprehensively?

The Economic Factors Killing the Middle Class

In the year 2003, three American economists – David Autor, Frank Levy and Richard Murnane – published a paper in the prestigious Quarterly Journal of Economics. Little did these economists know at that time that the dynamics described in this paper – titled ‘The Skill Content of Recent Technological Change: An Empirical Exploration’ – would reshape the politics of the Western world a decade or so later.

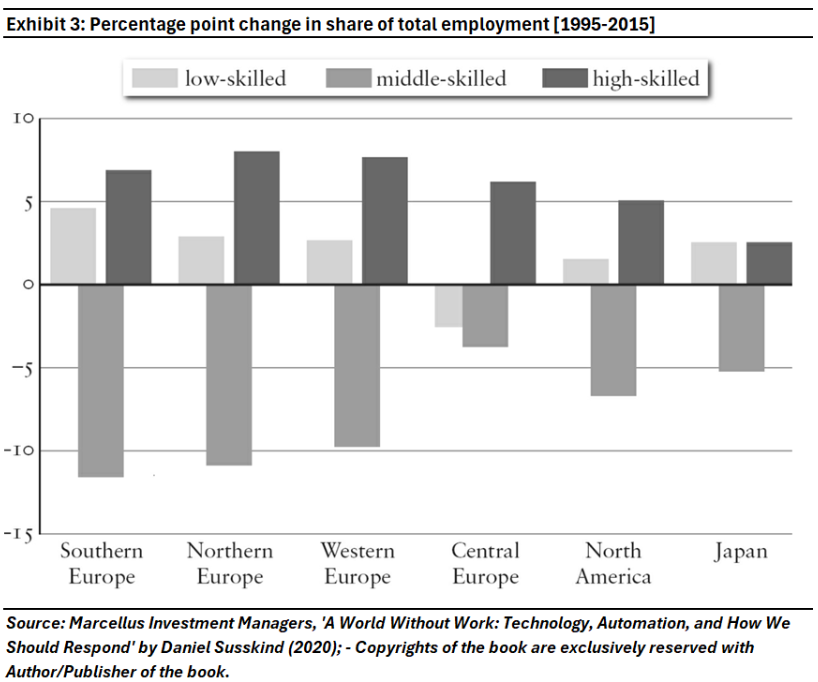

As Daniel Susskind says in his award-winning book ‘A World Without Work’, what these economists were able to explain in their 2003 paper is: “Starting in the 1980s, new technologies appeared to help both low-skilled and high-skilled workers at the same time – but workers with middling skills did not appear to benefit at all. In many economies, if you took all the occupations and arranged them in a long line from the lowest-skilled to the highest-skilled, over the last few decades you would have often seen the pay and the share of jobs (as a proportion of total employment) grow for those at either end of the line, but wither for those near the middle….This phenomenon is known as ‘polarization’ or ‘hollowing out’.

The traditionally plump midriffs of many economies, which have provided middle-class people with well-paid jobs in the past, are disappearing. In many countries, as a share of overall employment there are now more high-paid professionals and managers – as well as more low-paid care workers and cleaners, teaching and healthcare assistants, caretakers and gardeners, waiters and hairdressers. But there are fewer middling-pay secretaries and administrative clerks, production workers and salespeople. Labour markets are becoming increasingly two-tiered and divided. What’s more, one of these tiers is benefiting far more than the other. The wages of people standing at the top end of the line-up, the 0.01 per cent who earn the most….” – Susskind, Daniel. A World Without Work: Technology, Automation and How We Should Respond (p. 36). Penguin Books Ltd. Kindle Edition.

The theory propagated by Autor, Levy & Murnane for the West is almost perfectly applicable to India. In India, too, we now see clerical, secretarial and other routine work in offices & factories being automated. So far, AI is not required to automate these jobs e.g., you don’t need AI to replace a teller in a bank branch with an ATM. However, as AI gradually becomes sophisticated (and as generative AI makes the bots cleverer), it seems reasonably certain that more white-collar jobs will be lost. As Rishad Premji, Chairman of Wipro, puts it, “I think that two-three… elements that people think which are very important is the disruption of the technology process… the reality is, there are going to be some jobs that will disappear…“I think the good part is the opportunity to disrupt virtually every aspect of our life with the productivity that AI can bring is going to be incredibly powerful.” [source: Money Control]

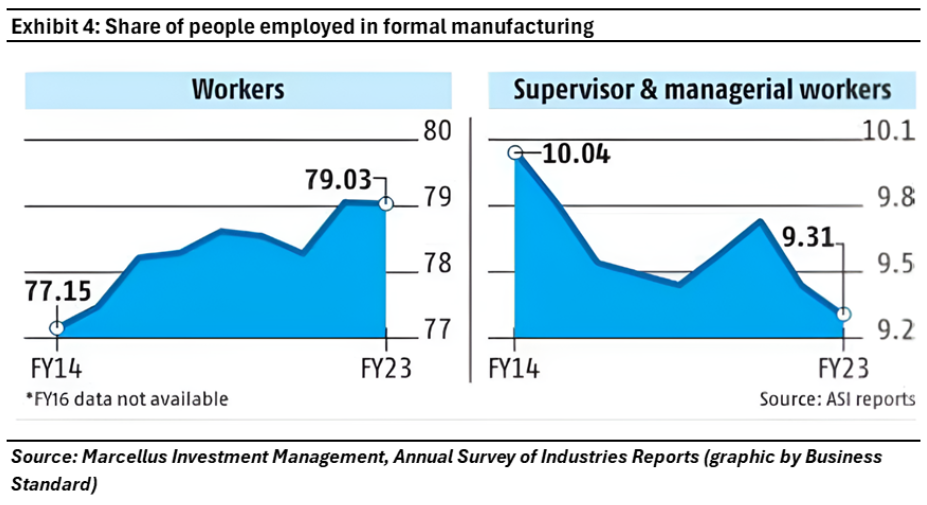

In fact, if we were to look at the recently published data in the Annual Survey of Industries, the number of supervisors employed in manufacturing units (as a % of all employed) in India has gone down significantly (see exhibit below).

PC Mohanan, former acting chairman of the National Statistical Commission (NSC), has said that “The decline in administrative job roles has been observed for quite some time now. Besides, the increasing trend of contractualisation and outsourcing by producers as a measure to cut input costs implies that many managerial and supervisory roles no longer exist. While workers are needed to produce and operate machinery, supervisors are no longer required for them.” [source: Business Standard]

The Social Factors Killing the Middle Class

Whilst it has been argued convincingly that the existence of the middle class in India pre-dates the arrival of the British (see, for instance, Manisha Pande’s book ‘Middle Class India: Driving Change in the 21st Century’ (2025)), it is evident that the Anglicized middle class as it exists in India today owes its birth to India’s former colonial rulers. To be specific, The British created the Indian Middle Class in the 19th century as it needed a layer of Indians (in their own image) who would govern the country (for the British).

This layer of Anglicized Indians became the leaders of the Indian freedom struggle towards the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the 20th century. Whilst these Indians rejected the British and sought independence from them, they did not reject British education and Western culture. In fact, they owed their careers, their influence and their wealth to British education & Western culture.

At Independence, this class of Anglicized Indians took over the levers of power from the exiting colonial masters. After Gandhiji’s assassination in 1948, Nehru was the leader and residing deity of this Anglicized class of Indians.

The result of the middle-class domination of the political and bureaucratic elite in post-Independence India was that govt policy & spending favoured the middle class – e.g. the large sums of money spent on building elite centres of higher education in one of the poorest countries in the world (and a country infamous for mass illiteracy) – even as the government paid lip service to socialism and claimed to focus on uplifting the poor. The middle class capture of the commanding heights of Indian politics from 1947 until the early 1980s helped the middle classes maintain their Anglicized way of life and perpetuated their obsession with the credentialism associated with higher education. In his book, the ‘Great Indian Middle Class’ (2007) Pavan Varma describes the middle class’s capture of post-1947 policymaking eloquently:

“There are other areas….in which the interests of the dominant coalition of which the middle class constituted an important part, hijacked the policies of the State, to the enduring detriment of those for whom the policies were supposedly formulated. Education provides a particularly striking example. A decade and a half before the Independence the Congress Provisional Governments in the states had introduced a scheme for Basic Education. In the Constitution adopted by free India in 1950, Article 45 provided for free and compulsory education for all children under the age of fourteen. The middle classes of India had always accorded great importance to education and this statement of intent could not but have their support. However, their demand was not for basic education which they had already acquired, but for higher education. It was their pressure notwithstanding the importance given at the policy level to primary education, which led to a most remarkable – and improper – growth in higher education. Given that resources were both scarce and finite, such a growth could have only taken place at the cost of other educational priorities. Not surprisingly, today India sends about six times more people to the universities and other higher educational establishments than China; however, roughly half of Indias population is illiterate, whilst China’s adult literacy rates are close to eighty per cent. In fact, there is little doubt that lopsided development of education in India is directly linked to the structure of India society, and ‘that the inequalities in education are, in fact, a reflection of the inequalities of economic and social powers of different groups in India. The educational inequalities both reflect and help to sustain social disparities…’

Today India has the largest number of out-of-school children in the world and one of the world’s largest reservoirs of trained and skilled manpower. The illiterate children come from poor households, mostly in the rural areas. The trained manpower has a largely middle-class and urban background. The responsibility for this dichotomy has to be laid squarely at the threshold of those who, in the initial years after 1947, were powerful enough to influence the direction of education policy in the own interest.” [The quote in boldface is from Amartya Sen’s ‘Selected Regional Perspectives’ (1997)]

There is another way the middle classes benefited through the 1960s, 70s & 80s – since they controlled the bureaucratic apparatus in India, they benefited from the rent seeking arising from using the levers of the ‘License Permit Raj’. That wealth in turn allowed them to get their next generation set up to further cream the benefits of a system in which a narrow Anglicized elite monopolised its grip on power in India (often through the entrance exams which gave the whole affair a veneer of legitimacy) whilst claiming to itself and to the broader world that they were promoting socialism and the upliftment of the downtrodden.

However, as we want further away from 1947, this Anglicized middle class found itself unmoored on several fronts: a) the poor gradually asserted their power through the ballot box and as they did so, political leaders from the grass roots started grabbing the levers of power; b) the middle found itself at odds with the politicians and new elites who were rising from the grass roots and had no affinity with Anglicized culture; c) after the first generation of post-Independence leaders died, the Anglicized class – obsessed as it was with credentialing and livelihood – found itself bereft of leadership.

The ascendancy of the BJP and of vibrant regional parties like TMC, BRS, TDP, DMK, AIADMK is the final nail in the coffin for the Indian Middle Class because: a) the new political strongmen/women have no affinity for Gin & Tonic drinking, convent-school culture and, in fact, are seeking to create their own version(s) of the Indian idiom; b) the core financial backing of most political parties now comes from baniya/entrepreneurial class rather than from the Anglicized elite; and c) the displacement of the Anglicized elite from positions of power in the public sector & academia robs them of the ability to ensconce other well-educated, bookish people (including their own progeny) in positions of power & influence.

To compound the problem for the ancient regime, the rise of AI & automation further robs the well-educated, Anglicized elite of lucrative positions of employment in the Indian private sector.

And thus the old elite dies and a new, entrepreneurial elite rises helped by the fact that just as the middle class monopolised political power in the first 40 years post-Independence, now the entrepreneurial class is consolidating its grip on political power.

The Political Factors Killing the Middle Class

In pre-Independence India, the middle class was supposedly very active in politics. Manisha Pande says in her book ‘Middle Class India: Driving Change in the 21st Century’ (2025) that the middle class played key roles in the Battle of Plassey (1757), in the revolt of 1857 and in the freedom struggle in the 20th century (which was arguably led by the greatest middle-class Indian ever, Mahatma Gandhi).

Be that as it may, in independent India the middle class has been notable for its refusal to enter politics on the premise that it is ‘dirty’ relative to the cosy confines of corporate life where the middle class feels safer even though most rational observers would argue, that the Boardroom of a Nifty company is just as much of a snake pit as the Parliament.

As a result, the core of the Indian political elite now constitutes of people either from working class backgrounds OR from newly ascendant political families (who have ruled Indians for the last three decades often by switching from one political party to another).

Its aversion to the rough & tumble of active political duty has cost the middle class a seat at the table and made it by and large a bystander (and at best a commentator) in India’s multi-layered democratic political system.

Such is its inability to engage in politics that the Middle Class is not even able to turn out to vote in elections in large numbers. In fact, electoral turnout is the lowest in the most prosperous enclaves of India’s largest cities as most middle-class Indians regard voting day as a public holiday. For example, in the 2019 general elections in Odisha’s Bhubaneswar, the voter turnout was 46 per cent, out of which only 10 per cent were from the middle class (source: Manisha Pande in ‘The Great Indian Middle Class’).

Unsurprisingly therefore, politicians rarely feel the need to cater to the middle class’s interests or listen to its grievances; the politician thus prioritises the poor for votes and the elite for their money (which greases the wheels of the electoral machine). Consequently, as Pavan Varma writes in ‘The Great Indian Middle Class’: “…democracy in India has ceased to be a genteel club where the poor are resigned to subordinate their interests in favour of the entrenched.”

A combination of the above plus an inability to come together on a pan-India basis with a cohesive set of demands & solutions has made the middle class almost irrelevant to the political discourse. As VS Naipaul noted in ‘India: A Million Mutinies Now’ (1990): “…everyone awakened first to his own group or community; every group thought itself unique in its awakening; and every group sought to separate its rage from the rage of other groups.”

Manisha Pande writes in ‘The Great Indian Middle Class’, “Politically, the middle class is divided on the issues of identity and nationalism. Each social group has its own definition of nationalism, which differs from the others….’

Thanks to its multitude of grievances, the middle class finds itself splintered not just on a pan-India basis, not just in a large metropolis like Mumbai but even within specific neighbourhoods in India’s megacities. This lack of cohesion means that even if a political leader were inclined to listen the middle class’s demands, she wouldn’t know which of their dozens of demands to cater to in order to garner a significant chunk of votes. The poor, on the other hand, are ready and able to offer their votes to the highest bidder. That makes them both supplicants in the Indian political system but also beneficiaries of the doles and subsidies dished out by the ambitious political elite which is happy to use the middle class’s tax payments to fund such expenditures.

- Elite consumption will continue to boom in India. For example, luxury car sales growth will continue to outstrip sales growth of cars priced below Rs 10 lakhs.

- We are seeing a revival in non-urban consumption as governments both at the Centre and in the states ramp up their generosity to those earning less than Rs 5 lacs per annum. This revival in mass consumption is highly likely to sustain.

- The middle 50% of India’s tax paying population has seen its income stagnate in absolute terms over the past decade. This implies a halving of income in real (i.e., inflation adjusted) terms. This financial hammering has decimated the middle class’s savings – the RBI has repeatedly highlighted that net financial savings of Indian households are approaching a 50-year low. This pounding suggests that products & services associated with middle class household spending are likely to face a rough time in the years ahead.

Note: the above material is neither investment research, nor investment advice. Marcellus does not seek payment for or business from this material/email in any shape or form. Marcellus Investment Managers Private Limited (“Marcellus”) is regulated by the Securities and Exchange Board of India (“SEBI”) as a provider of Portfolio Management Services. Marcellus is also a US Securities & Exchange Commission (“US SEC”) registered Investment Advisor. No content of this publication including the performance related information is verified by SEBI or US SEC. If any recipient or reader of this material is based outside India and USA, please note that Marcellus may not be regulated in such jurisdiction and this material is not a solicitation to use Marcellus’s services. All recipients of this material must before dealing and or transacting in any of the products and services referred to in this material must make their own investigation, seek appropriate professional advice. This communication is confidential and privileged and is directed to and for the use of the addressee only. The recipient, if not the addressee, should not use this material if erroneously received, and access and use of this material in any manner by anyone other than the addressee is unauthorized. If you are not the intended recipient, please notify the sender by return email and immediately destroy all copies of this message and any attachments and delete it from your computer system, permanently. No liability whatsoever is assumed by Marcellus as a result of the recipient or any other person relying upon the opinion unless otherwise agreed in writing. The recipient acknowledges that Marcellus may be unable to exercise control or ensure or guarantee the integrity of the text of the material/email message and the text is not warranted as to its completeness and accuracy. The material, names and branding of the investment style do not provide any impression or a claim that these products/strategies achieve the respective objectives. Further, past performance is not indicative of future results. Marcellus and/or its associates, the authors of this material (including their relatives) may have financial interest by way of investments in the companies covered in this material. Marcellus does not receive compensation from the companies for their coverage in this material. Marcellus does not provide any market making service to any company covered in this material. In the past 12 months, Marcellus and its associates have never i) managed or co-managed any public offering of securities; ii) have not offered investment banking or merchant banking or brokerage services; or iii) have received any compensation or other benefits from the company or third party in connection with this coverage. Authors of this material have never served the companies in a capacity of a director, officer, or an employee. This material may contain confidential or proprietary information and user shall take prior written consent from Marcellus before any reproduction in any form.