OVERVIEW

“Sometimes we are asked what it is we do all day – given we are not trading in and out of our holdings. One answer is that we are watching very closely the capital allocation decisions taken by the boards of the companies we hold – knowing that cumulatively and over time it is the caliber of those decisions that will determine the long term success, or otherwise, of our own investment decisions, made with your capital.” – Nick Train, co-founder of Lindsell Train Fund Management. (Link)

As we approach the end of FY20 and look back at the past two and half decades i.e. the time since Financial Services in India started becoming part of the private sector, there have been a select few individuals who have managed to successfully steer their organisations through the multiple crises that the Indian Financial Services industry has seen. In a series of blogs, we delve deeper into the decisions taken by these bankers not only because they have created financial institutions which have endured the test of time but also because they have had a major impact on the evolution of the broader Financial Services industry. While these men come from different backgrounds, they share two common traits which we believe are key to creating wealth – a high level of integrity and prudent capital allocation skills. In part I of this series we delve deeper into the key decisions made by the world’s wealthiest self-made banker – Uday Kotak.

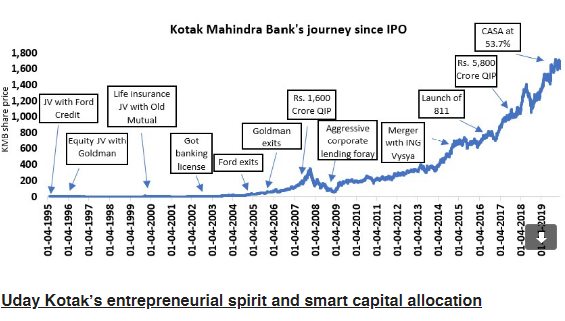

Uday Kotak’s entrepreneurial spirit and smart capital allocation

Warren Buffett’s observation: “No matter how great the talent or efforts, some things just take time. You can’t produce a baby in one month by making nine women pregnant” is apt for the financial services industry. As many who have tried and miserably failed have realised, Financial Services businesses cannot be built in a few years or even a decade’s time. Coming from a family of Kutchi Gujarati traders, Uday Kotak refused to join his family business and started a bill discounting business in 1985 from funds borrowed from friends and family. Uday Kotak’s entrepreneurial journey from the founding of Kotak Mahindra Financial Services Ltd. (KMFSL) in his family’s 300 square foot office to recently claiming the spot for the richest self-made banker in the world has been a journey of 35 years.

To cite an early example of Uday Kotak’s entrepreneurial acumen, in the mid-1980s when bank spreads used to be 10-11%, banks used to borrow at 6% and lend at 17%. Nelco, a Tata company used to borrow money for 90 days at 17% through bill discounting. Uday Kotak convinced his friends and family to lend him money at 12% which was in turn lent out to Nelco at 16% and that is how the bill discounting business started. It was a win-win for everyone – the depositors earned 12% on Tata risk vs. the 6% they earned on deposits and Nelco could borrow at 16% i.e. at 100 bps lower.

At the receiving end of another example of Uday Kotak’s innovation and customer centricity was Citibank. Citibank was the only bank disbursing car loans in 1989 and the lending rate used to be 27-28%. There was no way KMFSL could compete against the might of Citibank, but Citibank had one constraint – they could lend against cars only when the cars were available, and in the 1980s cars were in short supply in India. So, KMFSL started buying and booking cars in advance, because it usually took 6-8 months for cars to get delivered. Whenever a customer wanted a car, KMFSL could give a car along with the finance. They didn’t charge the customer a premium on the car, but the customer had to take a loan from KMFSL. The car finance business was where the spread was, and KMFSL was able to compete with a giant like Citi within 3 years of its incorporation.

Over the years, Uday Kotak has shown admirable capital allocation skills, whether it is in terms of distributing dividends, acquisitions, entering into joint ventures, buying stakes of JV partners or timing of QIPs. We have elaborated here are some of the key capital allocation decisions taken by Uday Kotak over the years:

- Mastering the virtuous cycle of generating and redeploying profits: Kotak Mahindra Bank (KMB) has had an average dividend payout ratio (i.e. % of profits paid out as dividends) of 2.9% over the last decade (FY09 to FY19). Since capital being the raw material of a financial services business, rather than distributing it as dividends, KMB has redeployed capital and generated an average return on equity of 14.5% on that capital over FY09 to FY19. To put things into perspective, the bank has cumulatively paid total dividends of ~Rs. 1,000 Cr (including Dividend Distribution Tax) on total profits of over Rs 34,800 Cr over FY09-19. As a result of the bank being able to redeploy 97% of its profits and consistently earn a decent RoE on it, KMB’s EPS grew at a ~23% CAGR during this time. This EPS growth has played a key role KMB’s share price growing at a CAGR of 34% over FY09-19.

- The merger that propelled KMB into the big league: KMB’s merger with ING Vysya Bank in April, 2015 was then the largest merger in India’s banking industry. Given the size of the merger, a misjudgement would have haunted Uday Kotak for years to come. KMB entered into a share swap deal when its stock was trading at ~4.5x P/B and ING was trading at 2.2x P/B thus effectively achieving multiple objectives at the same time: firstly, KMB didn’t have to pay any cash and hence diluted its stake by only 15%; secondly Uday Kotak pared down his promoter holding as required by RBI; thirdly KMB acquired a large SME loan book (the SME segment became 20% of the bank’s loan book from 7% prior to the acquisition); and fourthly, KMB got a large branch network in Southern India.

- Entering into joint ventures with the global leaders: Uday Kotak seems to have mastered the art of finding the right JV partners early on in his journey. Uday Kotak’s strategy playbook of entering into joint ventures with leading global players and then buying them out at the right time has been successfully executed with firms like Goldman Sachs, Ford and Old Mutual. The firm’s joint ventures with Goldman Sachs and Ford in 1996 helped it understand global best practices in broking, investment banking and automobile lending to the nascent Indian market. Similarly, KMB entered into a 76:24 joint venture with Old Mutual when it wanted to enter the life insurance business in 2001.

- The art of exiting joint ventures amicably: Not only did KMB learn from the largest and best global players but it was also able to end those joint ventures amicably while retaining those businesses. In an era when being acquired by foreign JV partners was the norm (just 3 months prior to Goldman’s exit from Kotak Securities, Merrill Lynch had bought out Hemendra Kothari’s 50% stake in DSP Merrill Lynch), KMB not only bought out the stakes of Ford, Goldman and Old Mutual but also ended the joint ventures amicably by paying a fair price to all JV partners. Old Mutual earned a 15% CAGR return on its original investment of Rs. 185 Cr when its 26% stake was bought out in 2017. Similarly, Goldman earned a 13% CAGR on its Rs. 100 Cr investment in Kotak Mahindra Capital and Kotak Securities when it was offered Rs. 330 Cr for its 25% stake in each of the entities. By the time KMB offered an exit to its JV partners, not only had Uday Kotak capitalised on the intangibles of imbibing global best practices but had also become India’s number 1 investment bank, brokerage company, automobile lender and the country’s 6th largest life insurer. KMB is now the only large Indian bank which owns 100% of all its subsidiaries whether be it broking, investment banking, insurance or asset management.

- Taking advantage of the financial crisis to foray into corporate banking: Until FY09, KMB’s loan book primarily comprised of retail loans (auto loans, CV loans, personal loans, home loans, etc.) with the share of retail loans being as high as 89% in FY08. However, the bank’s loan mix altered significantly post the financial crisis as the bank increased its focus on the corporate segment and cut down its exposure on the high-risk personal loan segment. Corporate loan book growth outpaced overall loan book growth in the coming few years as KMB capitalised on its relatively well capitalised balance sheet and superior asset quality to lend to blue chip corporates during the 2008-09 financial crisis. While the bank’s overall advances grew by 2% in FY09, the corporate loan book growth was 20%. Similarly, overall advances grew 32% in FY10 while the corporate book doubled during that year. As other lenders became risk wary or faced the heat of the financial crisis, it gave KMB the opening it was looking for to enter the balance sheets of large Indian corporates. By the end of FY10, a quarter of KMB’s loan book comprised of corporate loans vs. 11% in FY08 making it a much more stable bank with a balanced loan book mix.

- Timing QIPs properly: Typically, fast growing lenders raise capital every three years or so as their ROE is below their loan book growth thus putting downward pressure on their regulatory capital ratios. In contrast, inspite of its rapid EPS growth, KMB has raised capital in the form of QIPs only twice – in 2007 and in 2017 – thus ensuring minimum dilution by raising equity when markets have been at their peak. On a lighter note, for investors who are still looking for a way to time the markets despite the futility of such a practice (for a more detailed account on the futility of timing the market, please read our March 2019 newsletter), a QIP from KMB is probably a good sign of the Indian stock market indices being near their peak.

- Learning from mistakes: Even the greatest bankers make mistakes. For example, Wells Fargo, the most celebrated of the modern day American retail banks, suffered from a nasty “cross-selling” scandal a four years ago wherein staff seemed to have forced clients to accept credit and debit cards in order to boost their cross-selling stats (which in turn was linked to their compensation). The episode culminated in Well Fargo’s legendary CEO John Stumpf stepping down. Uday Kotak’s darkest hour seems to have been the late 1990s NBFC crisis in India. During this crisis, when many thousands of NBFCs had to shut down in India, Uday Kotak’s NBFC – KMFSL – too suffered from a funding crunch. The intensity of the resultant crisis seems to have been a key trigger for this Mr Kotak to pursue a banking license in earnest. In 2003, the RBI gave Uday Kotak a universal banking license and the rest is history.

Investment implications

Lending businesses are necessarily highly leveraged businesses with a high reinvestment rate. This unique characteristic of financial businesses further amplifies the impact of capital allocation decisions made by the CEOs of these organisations. As Uday Kotak has shown, good capital allocation can lead to extraordinary results while poor decisions can pose an existential threat to a bank or NBFC. Even though Kotak Mahindra Bank is currently sitting on excess capital, we believe Uday Kotak’s prudent capital allocation skills will ensure that KMB generates returns well above cost of capital in the times to come. Therefore, we continue to focus our energies on finding and staying invested in conservative financial services businesses which have a long historical track record of having made good capital allocation decisions. (for a more detailed account of our Financial Services holdings please read our November 2019 newsletter)

Disclosure: Kotak Mahindra Bank is part of most of Marcellus’ portfolios.

Tej Shah is a portfolio counsellor at Marcellus Investment Managers