OVERVIEW

Given the likelihood of elevated inflation as Cold War II commences, the worst possible thing that investors can do is seek the safety of fixed deposits, Government bonds, corporate bonds and other fixed income investments – inflation will radically erode the real value of such investments. The most sensible method to deal with a scenario of healthy economic growth alongside elevated levels of inflation is to invest in high quality companies which have the pricing power to pass on the rise in labour & raw material costs on to their customers and thus significantly outperform the market

“I would bet on globalization slowly being in abeyance. I think with the benefit of hindsight, we will realize that 2007 was not just the peak year of the finance boom, but also the peak year of globalization, like maybe 1913. Happily, it hasn’t resulted in a world war, at least not yet, but I think we are in this period where globalization is steadily pulling back. And so, you want to be in places or industries that are levered to things other than globalization.” -Peter Thiel quoted in ‘Understanding Peter Thiel & René Girard: Fascinating Quotes from their Books and Interviews’ by BW Martin, 2nd Edition (p. 56), Kindle Edition.

Cold War II is now officially underway

Over the past five years we have grown accustomed to China and America squaring off on trade restrictions and Covid-19 even as the Americans had grown habituated to the Russians meddling in American elections. With Russia’s assault on Ukraine, these smouldering hostilities have now been escalated to what is effectively Cold War II. The sanctions on Russia which have followed the assault on Ukraine, and China’s unwavering support for Russia in the midst of all this is likely to reverse much of the globalisation dynamic which was set in motion after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989. As Francis Fukuyama says in the Financial Times, “The horrific Russian invasion of Ukraine on February 24 has been seen as a critical turning point in world history. Many have said that it definitively marks the end of the post-cold war era, a rollback of the “Europe whole and free” that we thought emerged after 1991, or indeed, the end of The End of History.” (Putin’s war on the liberal order, 2022)

Russia and China have for several centuries now, been authoritarian countries with strong centrally run states and with little or no tradition of democracy. The two power structures are a legacy of how history has played out for them.

Russia has been a joined up, centrally run, and ethnically united State since 1550. The Russians are largely Slavic, Baltic, and Ugric people, and practice orthodox Christianity. Their traditional occupation is agriculture & farming. The thrashing received from the nomadic Mongols (who knew nothing about farming) in the 13th century united the Russians. For the past 500 years the Russians have repeatedly had to go to war to defend their Western border (with Europe – think Napoleon, think Hitler) and their Eastern border (with the Mongols & Turkic people). With no natural boundaries protecting it, Russia has been a land under almost constant attack (much like the Punjab). Protecting the country has therefore meant that almost every strata of Russian society has had to be involved over the past century in fighting wars. Since the Russians have seen that losing a war meant being subjected to loot, rape and enslavement, this “we are under attack” mindset resulted in enormous social cohesion amongst the Slavic people. Basis centuries of experience, the world outside Russia is seen (by the Russians) as a predator perpetually looking to break down Russian defences. Communism was simply one manifestation of the need to create a fresh ideology for “Us vs Them”. It is secondary whether the leader is a Royal tsar, a Lenin or a Putin – Russians have, for 500 years now, united around a strong leader in Moscow. Rarely has the leader been democratically elected. Almost always the leader has been a strongman.

China has been a centrally managed state – with no tradition of democracy or of pluralism – for even longer than Russia. As Francis Fukuyama explains in “The Origins of Political Order” (2011), 2000 years ago, China successfully created a centralised, uniform system of bureaucratic administration that was capable of governing a large population and massive amounts of territory. Uniquely for its time, recruitment for the Chinese civil service was impersonal and merit based. China did NOT have democracy but what it had in terms of system of governance would take Europe another couple of millennia to build.

Many of the institutions which are used to govern modern China were created in 200 BC when the king of Qin conquered all his rivals and established a single empire, uniformly imposing institutions first developed in Qin over much of northern China. By 200 BC, standing armies had been created in China to enforce common rules and bureaucracies had been created to collect taxes, build roads and irrigation systems and mandate weights and uniform measures. This also led to the creation of a common literary language for all of China. The Qin state in a way was very similar to the modern authoritarian state where a dictator determines property rights, doles out justice, appoints generals & judges and civil servants. China thus created the first strong modern state but one without any accountability. Compared to other civilisations the Chinese state’s able to concentrate enormous power is remarkable.

India, in this regard, is very different from China and Russia. India’s default has been to be a series of small, squabbling kingdoms and principalities punctuated by brief periods of political unity. Autocracy has been very difficult to establish in Indian politics. Because unlike China, India never experienced multi-century wars, the Indian state never experienced the extreme social mobilization requirements of the Chinese state.

Moreover, the rise of the Brahmins as a separate power centre in ancient India, immediately put a check & balance on the power of the Kshatriyas. In China, the priests never became a separate power centre – they owed their power to the king.

Thirdly, in India, rise of the Jatis created a third level of order that China never had. In India, Varna and Jati – not the king and not the rule of law – formed the bedrock of social order and severely limited the power of the state to penetrate and control it. Not once was the entire area where Indian culture has permeated – from Afghanistan to Bali – ruled by a single ruler and nor did this area have a single language of governance. Interestingly therefore the only rulers who have been able to unite India are foreign invaders whose political power rested on a different social basis. In fact, accounts of India which pre-date the arrival of foreign invaders show that the Raja’s mandate was to keep his subjects happy and protect them from neighbouring tribes rather than lord it over them Chinese style. In return for this protection the subjects paid a tax to the Raja. Thus, from the ancient texts and epics onwards, the Indian king is far more accountable to his subjects than the Chinese or Russian dictator. In this regard, India is very similar to the United States or the countries in Western Europe. And so, when it comes to choosing a side in Cold War II, India’s tendency toward accountability in governance is likely to nudge India towards to American-European democratic bloc alongside Japan.

And so, the starting line-up for Cold War II looks as follows: an authoritarian Eurasian bloc led by China & Russia and their satellite states like Pakistan, North Korea, Myanmar, Cambodia, etc versus a democratic bloc led by USA, the EU, the UK, India, Japan and Australia.

How Cold War II will impact India.

With India inclining more towards the democratic bloc which seems likely to create an Asian version of NATO (given China’s increasingly menacing behaviour vis-a-vis Taiwan, India, and Australia), a quid pro quo between the countries in the democratic bloc and India seems to be on hand. This essentially would be in the form of increased Foreign Direct Investments (FDI), Foreign Portfolio Investments (FPI) and trade inflows (largely in the form of the Western world outsourcing much of its white collar office work in IT Services, Finance, HR, Payroll and Marketing to India) in return of continued allegiance with the democratic bloc. The implications of these capital and trade inflows for India’s economy are significant.

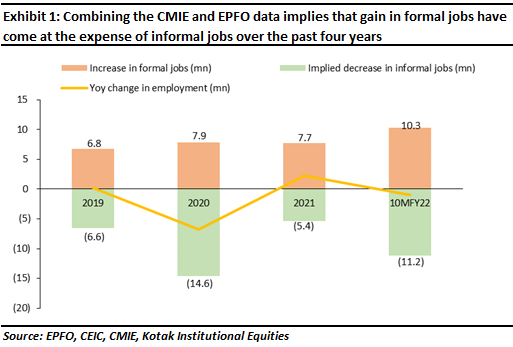

Services account of US$ 1.3 trillion of India’s US$ 2.6 trillion economy currently. India’s total export of Services currently stands at US$ 0.25 trillion (i.e., around 9% of GDP as of today). Given that the combined Services sectors of USA, Canada, the UK, and the EU currently stands at US$ 15.2 trillion, even if we assume that a mere 10% of this is outsourced to India, India’s Services exports a decade hence could be around US$ 1.5 trillion implying a ten-year CAGR of 20%. All other things being equal, this would add approximately 1.2% points each year to India’s nominal GDP growth rate over the next ten years, making Services almost 21% of GDP (source: Bloomberg; data considered in nominal terms). Such a blast off in Services exports in turn would become a strong driver of formal sector job creation in India. Data from EPFO and CMIE already point to a rapid surge in formal sector job creation over the past three years – see chart below which shows that India added 33 mn jobs in the formal sector over FY20-22.

Exhibit 1: Combining the CMIE and EPFO data implies that gain in formal jobs have come at the expense of informal jobs over the past four years

Thanks to the surge in formal sector job creation in India alongside the boom in the Services sector in India, wage inflation is likely to sustain at mid-teens over much of the next ten years. This alongside: (a) China’s increasing reluctance to be the manufacturing centre of the world for cheap chemicals, cheap toys & electronics, low end synthetic textiles, etc; and (b) the disruption of global supply chains as the democratic bloc brings stuff back home that was hitherto imported from China, is likely to result in CPI inflation in India staying well above 6% (i.e., the upper end of the RBI’s comfort range) for much of the next decade.

Inflation is an ally of high quality stocks

Given the likelihood of elevated inflation as Cold War II commences, the worst possible thing that investors can do is seek the safety of fixed deposits, Government bonds, corporate bonds and other fixed income investments – the odds are high that inflation will radically erode the real value of such investments. In fact, over the past twelve months, investors in the Indian Government’s ten-year bonds have got a meagre 2% return on their investment (source: Bloomberg), which does not even exceed inflation rate, making people lose their money in real terms.

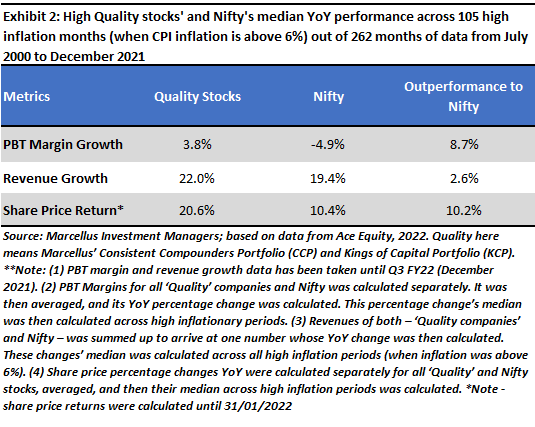

The most sensible method to deal with a scenario of healthy economic growth alongside elevated levels of inflation is to invest in high quality companies which have the pricing power to pass on the rise in labour & raw material costs on to their customers and thus significantly outperform the market – both on fundamentals and on share prices (see our 21st February’s note, Busting popular macroeconomic myths and see Exhibit 2 which is taken from this note).

The impact of high oil prices

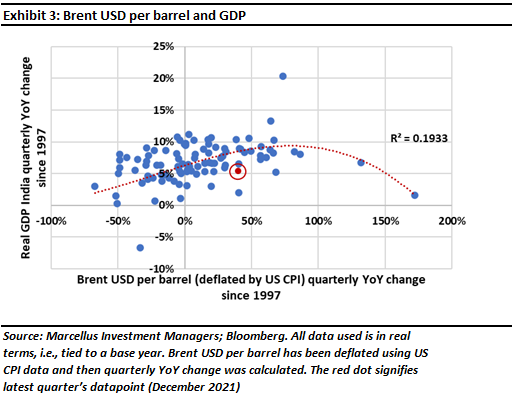

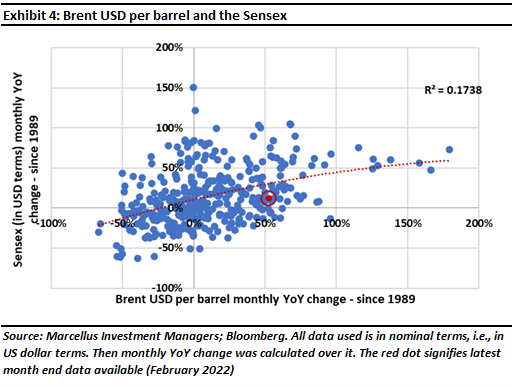

Indian investors routinely fret over rising commodity prices and especially, rising oil prices. However, if we analyse the link between crude oil prices, the Indian economy and the Sensex, a far less worrisome picture emerges.

Exhibit 3 shows an initial positive relationship between the crude oil price change and the real GDP change for India. Understandably however, once the oil price rise exceeds 100% YOY, the relationship becomes negative i.e., the rise in oil prices begins to hurt economic growth. Presently, according to the red dot in the chart, we are well within the rising phase of the chart, meaning that the surge in crude oil prices that we have seen so far is unlikely to materially impact economic growth. Interestingly, when it comes to the relationship between crude oil prices and the Indian stockmarket, the relationship is positive i.e., a rise in oil prices correlates with a rise in the Indian stockmarket – see Exhibit 4.

Investor implications

As mentioned above, investing in fixed deposits and bonds will be tantamount to throwing your money out of the window over the next few years. On the other hand, investing in high quality stocks i.e., companies with pricing power, will not only allow you to deal with the damaging impact of inflation, it should also allow you to benefit from the incipient economic recovery in India. For those who need more conviction on this matter we have presented below a case study which explains how this dynamic works.

A straightforward way to understand the limited impact of rising crude prices and rising inflation on high quality stocks is to look at namely Asian Paints.

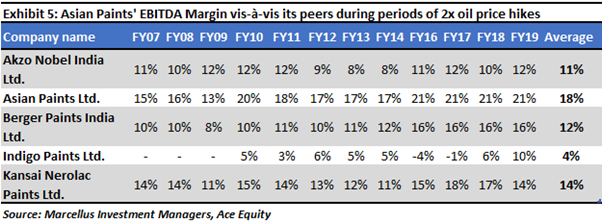

If we try to identify periods of 2x rise in crude prices, three such episodes emerge: Jan ’07 to Jul ’08, May ’10 to Mar ’11, and Mar’16 to Sep ’18. In majority of such episodes Asian Paints’ profit margin did NOT get compressed, making its average EBITDA margin stand way higher at 18% than its peers, as evidenced in exhibit 5.

The primary reason for such sustained EBITDA margins in Asian Paints is their high pricing power in their industry. The drivers of this pricing power are not price hikes but:

- Playing the ‘volume’ game: due to modest price hikes leading to improved affordability and coupled with accelerated penetration among geographies (tier 3/4/5 cities), the company has improved their pricing power, thereby not letting their profitability hit.

- Market share gains: incremental efficiencies in operations help them capture markets, which competitors cannot do without any price hikes.

- Defence against price wars: company’s competitive advantages are so well established; they don’t feel the need to get into price wars to eliminate competition and take a hit either on the product quality or their profit.

Due to these three drivers, companies like Asian Paints are not impacted by short term macroeconomic imbalances like oil price hikes. In fact, such circumstances help champion franchises like Asian Paints to gain market share whilst their competition suffers.

Note: Asian Paints and Berger Paints are part of many of Marcellus Investment Portfolios. The authors by dint of their investments in Marcellus’ portfolios also have investments in these stocks.

Nandita Rajhansa and Saurabh Mukherjea are part of the Investments team in Marcellus Investment Managers.

Note: the above material is neither investment research, nor investment advice. Marcellus does not seek payment for or business from this material/email in any shape or form. Marcellus Investment Managers Private Limited (“Marcellus”) is regulated by the Securities and Exchange Board of India (“SEBI”) as a provider of Portfolio Management Services. Marcellus is also a US Securities & Exchange Commission (“US SEC”) registered Investment Advisor. No content of this publication including the performance related information is verified by SEBI or US SEC. If any recipient or reader of this material is based outside India and USA, please note that Marcellus may not be regulated in such jurisdiction and this material is not a solicitation to use Marcellus’s services. This communication is confidential and privileged and is directed to and for the use of the addressee only. The recipient, if not the addressee, should not use this material if erroneously received, and access and use of this material in any manner by anyone other than the addressee is unauthorized. If you are not the intended recipient, please notify the sender by return email and immediately destroy all copies of this message and any attachments and delete it from your computer system, permanently. No liability whatsoever is assumed by Marcellus as a result of the recipient or any other person relying upon the opinion unless otherwise agreed in writing. The recipient acknowledges that Marcellus may be unable to exercise control or ensure or guarantee the integrity of the text of the material/email message and the text is not warranted as to its completeness and accuracy. The material, names and branding of the investment style do not provide any impression or a claim that these products/strategies achieve the respective objectives. Further, past performance is not indicative of future results. Marcellus and/or its associates, the authors of this material (including their relatives) may have financial interest by way of investments in the companies covered in this material. Marcellus does not receive compensation from the companies for their coverage in this material. Marcellus does not provide any market making service to any company covered in this material. In the past 12 months, Marcellus and its associates have never i) managed or co-managed any public offering of securities; ii) have not offered investment banking or merchant banking or brokerage services; or iii) have received any compensation or other benefits from the company or third party in connection with this coverage. Authors of this material have never served the companies in a capacity of a director, officer or an employee.