OVERVIEW

The two most of common ways of accessing the stock market – mutual funds and brokerage accounts – are relatively expensive for ordinary Indians. If the Indian stock market is to be taken to the masses, the highly successful National Pension Scheme construct looks to be the most likely vehicle which can serve this purpose.

After hitting a Covid-19 induced low in March 2021, the Nifty50 has doubled, driven both by foreign flows (FPI inflows into the Indian stock market amounted to US$ 14 bn over FY20-21)1 and domestic inflows (amounting to US$ 25 bn over FY20-21)2. The sustained vigour of this bull run has attracted millions of new investors into the Indian stock market – as per SEBI, 14.2 mn new investors have entered the stock market over the past 12 months3. In fact, prior to Covid’s onset in March 2020, there were ~11Mn active investors in India; over the past 18 months this number has more than doubled to ~25Mn active investors.

This bull run is not a flash in the pan. Over the past decade the Nifty50 Total Return Index (TRI) has compounded at 11% per annum4 and created US$1 trillion of wealth. The stock market has therefore become a potent source of sustainable wealth creation in India. It stands to reason therefore that if the wealth created by the stock market spreads across the country, it gives free market reforms a degree of mass legitimacy that it has hitherto lacked in India. Furthermore, in a country where the RBI says a mere 5% of household wealth is in the form of financial assets, the stock market can potentially drive financialization of wealth5.

However, there is good reason to believe that this is NOT happening. In other words, the beneficiaries of the rise in the Indian stock market are a privileged minority of Indian investors. Data from AMFI, the mutual fund trade body, shows that 84% of mutual fund investors (by value of assets) come from the 30 largest cities in India6.

So why is this happening? Given the ease with which Demat accounts can be opened and the extensive network of mutual fund distributors, why are the masses not investing in the stock market where the overall household financial savings rate is typically around 20% of income7?

The answer mainly revolves around the cost of accessing the stock market through Demat accounts and mutual fund folios.

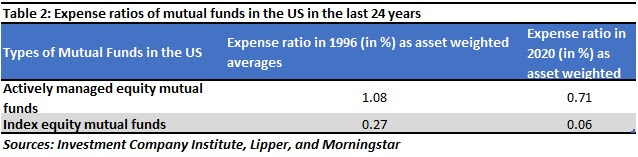

Comparing the cost of investing in mutual funds in India versus the United States throws up some interesting insights. In India, the cost of investing in a large cap equity mutual fund is around 1.8% (which falls to 1.1% if the investor goes “direct” i.e., without a distributor) – see table 1. Because these schemes struggle to beat the benchmark (see the ‘median’ performance in table 1), this is an expensive way to access the stock market.

In contrast, the cost of an actively managed mutual fund in the USA is around 0.7% – see table 2. Furthermore, several index funds in India charge fees north 10bps whereas the cost of such funds in the US is 6bps.

A more detailed comparison of the relative cost of investing in the two countries highlights the underlying source of the problem. The cost of direct large cap mutual fund investing in India versus the US – 1.1% vs 0.5% – can be justified by the colossal scale of the US asset management industry which is almost 15x the size of the Indian industry. However, the cost of ‘distributing’ (which is distinct from the cost of ‘manufacturing’) large cap equity mutual funds in India is very high at around 0.6% (see the last two columns of table 1 above). This distribution cost pushes the expenses of large cap equity mutual fund investing in India into unaffordable territory.

Beyond mutual funds, the other popular way for investors to access the Indian stock market has been via online discount brokerages. Here too we find the cost opening and opening a Demat account are relatively high in spite of the rise of discount brokerages. For the large discount online brokerages in India, the brokerage charge for intraday equity trading ranges from 0.03% to 0.05% and around Rs300 for account opening and maintenance each8 whereas a discount brokerage like Robinhood in the US operates with a $0 commission fee for trading and $0 as account opening and management fees9.

So, given the expenses associated with accessing the Indian stock market, how can its benefits be taken to the masses? The answer lies in one of the least talked about but most effective forms of savings in India – the National Pension Scheme (NPS).

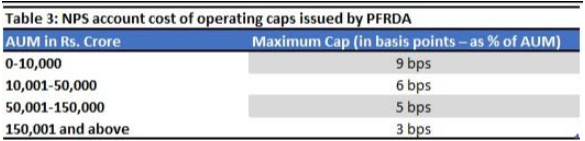

Launched in 2004, the NPS has strengthened even though the manufacturers of the product have spent almost no money publicising it. The NPS is a collection of low-cost funds (index funds which mimic the benchmark index) inside a low-cost pension wrapper with some tax breaks thrown in for the saver. As a result, it allows everyone – rich and poor – to participate in the rise of the stock market at minimal cost. As of August 2021, Rs 6.3 lakh crores was being managed under the NPS10. The cost of operating an NPS account is capped by the PFRDA, the pensions regulator, using a sliding scale:

Source: Live mint – NPS fees set to rise, 2021

|

|