OVERVIEW

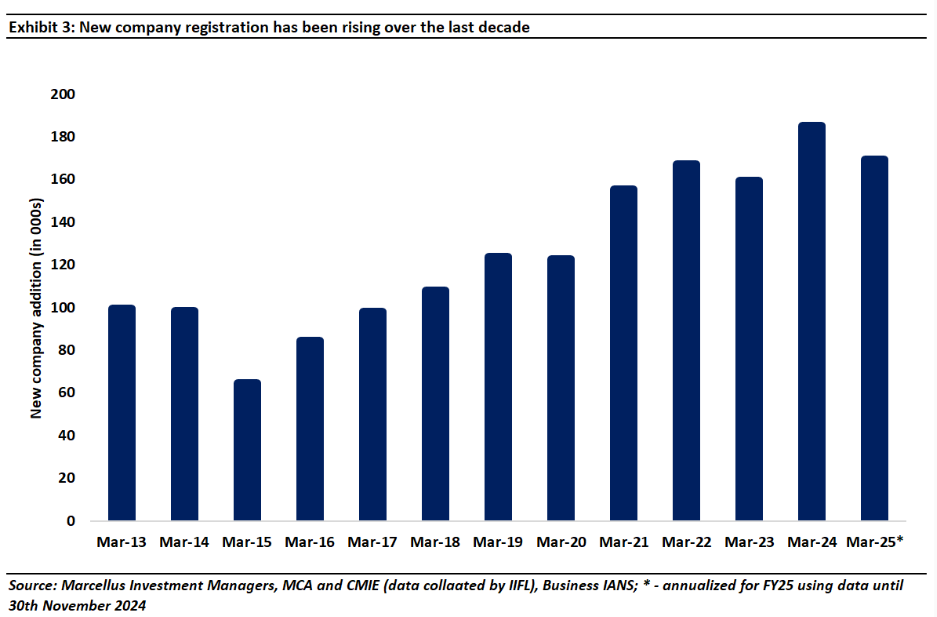

Even as conventional white-collar employment becomes a tricky proposition, entrepreneurial opportunities are proliferating in modern India. For educated Indians, this shift – from a white-collar professional’s mindset to an entrepreneurial mindset – requires considerable attitudinal retooling. Ironically, those Indians who are able to make this shift are succeeding not just as entrepreneurs but also in what is still the apex of India Inc, the boardrooms of the Nifty50 companies.

‘Don’t get fooled into thinking you have a lifelong career. At any moment, you need to be prepared to be independent and stand on your own two feet. If you prepare yourself for that, I think you are going to have a much better sort of ride along the way. So think about yourself as self-employed.’ — Ravi Venkatesan, former chairperson, Microsoft India” {Source: Mishra, Pankaj. Against the Grain: Lessons from the Outliers (p. 256). Penguin Random House India Private Limited. Kindle Edition}

Scarce jobs versus abundant entrepreneurial opportunities…

“Nestled in the crowded bazaar of Jail Road Market in New Delhi is a tiny shop selling colourful kurtas and pants for women, a common business in this neighborhood and in hundreds of similar markets across northern India. However, the owner of this shop and her story are anything but common. The owner is Jasmeen Kaur, creator of the now famous words ‘So beautiful, so elegant, just looking like a wow!’

Kaur shot to fame with this catchy phrase when Bollywood star Deepika Padukone recited it on social media and made it famous. The rise of Instagram and social media, as well as their accessibility to millions of Indians, ensured that the phrase ‘looking like a wow’ became ‘viral’ and made Kaur a celebrity, potentially creating a pan-India—as opposed to local—market for her wares. She signifies the rise of a new India; an India where polished English and high-profile university degrees and MBAs are no longer a prerequisite for success.” – Nandita Rajhansa & Saurabh Mukherjea in ‘Behold the Leviathan: The Unusual Rise of Modern India’ (2024), page 77.

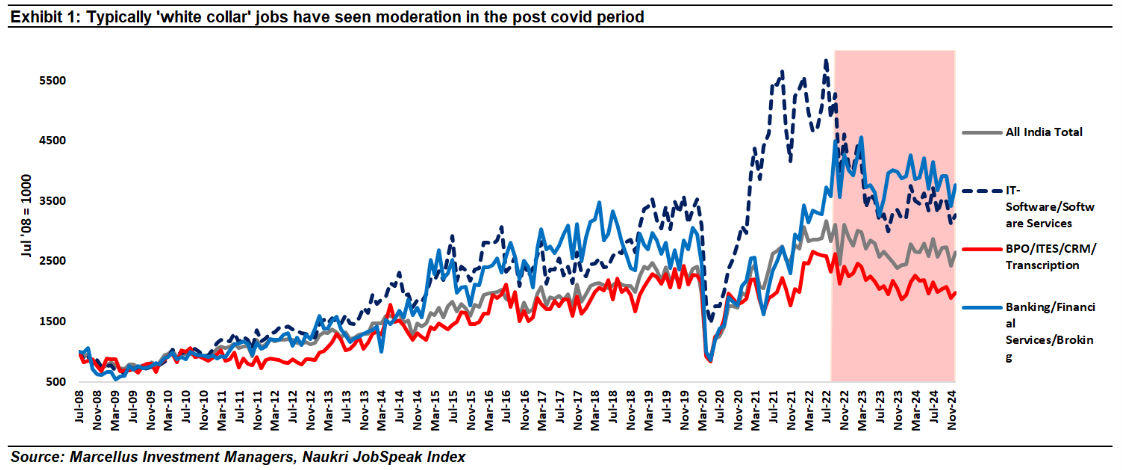

As shown in the opening chart of this note, conventional white-collar jobs continue to dwindle in the post-Covid world. Whilst the reasons behind this are manifold e.g. the lack of private sector capex, the rise of automation & AI in offices & factories (see our blog from 11th Dec 2024 on the lack of middle-class jobs in India ), the net result is a reconsideration of career priorities for most Indian professionals.

Even for the fortunate few who are getting jobs, wage growth in excess of inflation is proving to be elusive as even middle management jobs are being replaced by tech-based supervision of workers. Research from Citigroup shows that after adjusting for inflation, growth in wages for listed Indian firms – a proxy for earnings of urban Indians – has remained below 2% in 2024, well below the 10-year average of 4.4%.

…is leading to a reconstitution of the Middle Class

“Salaryman (サラリーマン, sararīman) is an originally Japanese word for salaried workers. In Japanese popular culture, it is portrayed as a white-collar worker who shows unwavering loyalty and commitment to his employer, prioritizing work over everything else in their life often at the expense of their family. “Salarymen” are expected to work long hours, whether overtime is paid or not.” – Source: Wikipedia

The gradual shrinking of the economic space within which white collar professionals operate, and the blossoming of the Indian entrepreneur has several ramifications for the distribution of wealth, power & influence in India. Going a level deeper, what constitutes desirable or ideal behaviour for an aspirational Indian is also changing as wealth & power shift from corporate hierarchies to family run businesses. The salaryman (& salarywoman) is finally ceding space – economically, financially, socially and politically – to the entrepreneur. (Refer to our 23rd January 2025 note on the fading political power of the conventional middle class in India, India’s Middle Class is Losing Ground to the Rich & the Poor)

Income Tax data shows that 227K Indians are filing annual tax returns in excess of Rs 1 crore. This count (of Indians earnings more than Rs 1 cr) has jumped 6x in the past decade. However, most of these fortunes are being made by “Octopus” families i.e. entrepreneurial families who generate income from a mix of running businesses, having a stake in local politics, investing in the stock market and investing in real estate development (more details on them follow further in the blog).

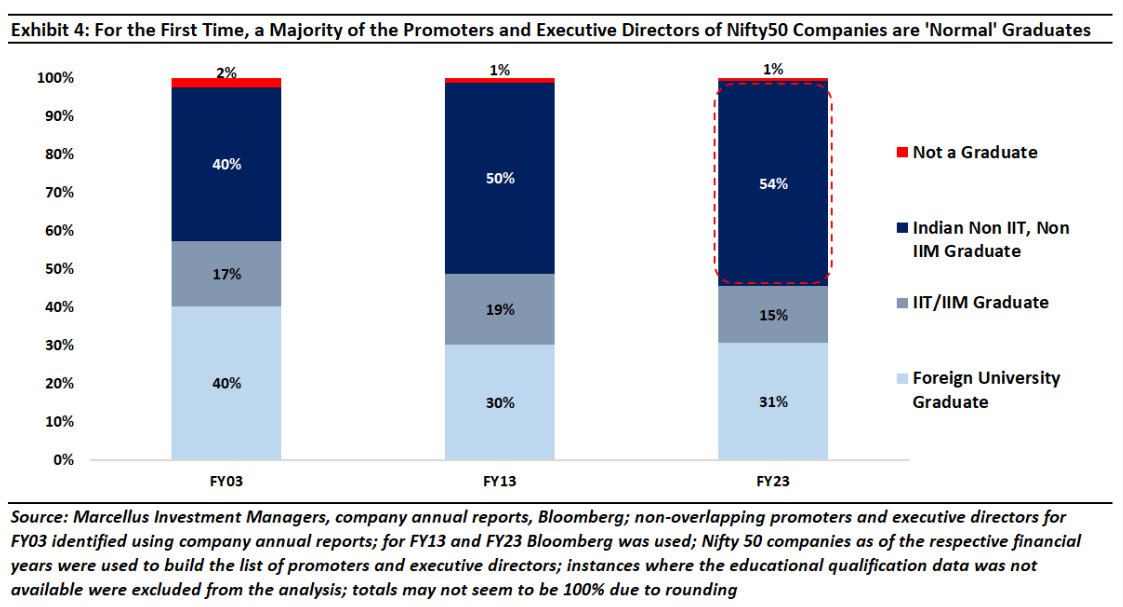

Very few of these high earners in India come from the classical middle-class route of university education followed by a rise up the corporate ladder. In fact, for the first time in the last twenty years, a majority of the promoters and executive directors of the Nifty 50 companies are neither from an IIT/IIM nor graduates from any foreign university. This is remarkable, because twenty years ago, in FY03, this non-elite figure was just 40 per cent, rising to 50 per cent in FY13. What the chart below shows is that the majority of the largest fifty companies in the country today are run by people who studied in non-elite educational institutions.

The rise of “Octopus” professionals in the big cities that are reconstituting the middle class

Whilst Octopuses in small-town India are owners of small businesses that go on to become mini-conglomerates, the big city Octopuses operate in a different way from their small-town cousins. In particular, they are likely to have a high skill quotient in terms of technical qualifications, which they will deploy to get well-paid jobs in India Inc. As India’s leading companies continue gunning out profit growth of 15 per cent per annum, the number of highly paid executives who manage these companies continues to burgeon. To hold on to their best talent, these companies will:

(a) Pay Their Executives Well. The Economic Times says that in the listed company universe, there are 1,161 individuals in the country who have an annual pay packet of Rs 1 crore or more

(b) Give Their Executives Equity-Based Compensation, which will then compound with the share price of the company, thus implying, at the market-wide level, around four times growth in wealth every decade.

Furthermore, the most ambitious of the corporate Octopuses are likely to quit to create their own start-ups, where a combination of their equity ownership alongside venture capital or private equity funding could make them dollar millionaires in the span of a few years.

Thus, the-big city octopuses will be a combination of listed-company owners (there are around 6,000 such families in India), venture capital- and private equity-backed company owners (which we estimate number approximately 6805) and the senior talent working in these companies.” – Nandita Rajhansa & Saurabh Mukherjea in ‘Behold the Leviathan: The Unusual Rise of Modern India’, pg. 110.

Differences between traditional Middle Class mindset vs Entrepreneurial mindset

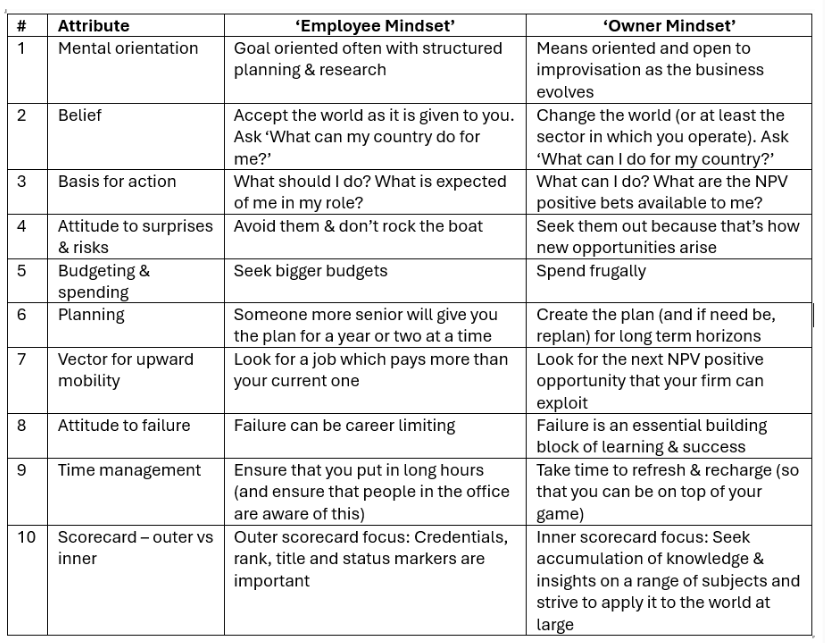

If the real world were the world described by Economics textbooks then we would expect to see a rapid flow of educated professionals migrating from the air-conditioned offices and bountiful canteens of India Inc into the entrepreneurial sphere. However, the real world is not that simple. There are a number of skills & mindset differences between what helps one succeed in a large Indian corporate versus what helps, and Indian entrepreneur succeed. The table below is our attempt to capture some of the more important differences.

Source: Marcellus Investment Managers, inspired by the table given by Mukesh Sud & Priyank Narayan in their book “Leapfrog: Six Practices to Thrive” (2022).

Broadly speaking, there four dimensions along which the skillsets needed to succeed in a structured corporate environment differs from what works in the entrepreneurial set-up in India:

- Planning & strategizing: To what extent am I a master of my own destiny versus the destiny imposed on me by external circumstances? How many variables are in play when it comes budgeting, strategic planning and execution?

Executive life, especially in a large company, is about meeting targets successfully, consistently and doing so with as little drama as possible. Exceeding targets regularly marks one out as a high-potential employee destined for high office. Pay rises, promotions, executive training, etc follows. Such an environment prizes “doers” i.e. people who can get the job done of hitting or beating the annual target.

In hierarchical executive constructs such as these if an exigency like a Global Financial Crisis or Covid hits, the executives look to the CEO, the Board or the promoter for a new strategy to guide the company though choppy waters.

In contrast, in an Indian entrepreneurs life, she is the “doer”, and the “thinker” and mega crises come along not once a decade but more like a once a year. When these episodic crises hit the company, the entrepreneur has to think on her feet, strategize, rally the troops and execute swiftly and decisively if she’s to save her enterprise. Strategy, planning and execution blur into the one fluid chain of thought in such an environment. Successful entrepreneurs therefore are those rare people who can be great thinkers and outstanding doers. Here is one such entrepreneur:

“‘If you are an entrepreneur, ask yourself: Are you a thinker or a doer? In my case, I have been both. This thinker–doer thing is something I toggle between…think what makes me a little more unique is that I am a thinker–doer in both public and private space. In the private space, I have done a lot of doing, in terms of my work in Infosys, mini start-ups, etc. But I have also done a lot of thinking about the future of financial services and given talks and stuff like that. So I did both thinking and doing here. Again, in the public sector, I have done thinking through my two books [Rebooting India: Realizing a Billion Aspirations and Imagining India: The Idea of a Renewed Nation], whereas the doing part is in Aadhaar, UPI, EkStep and all. So, if you draw a four-by-four—thinker, doer, public, private—I am in all four quadrants. Probably not too many people have done that.’” — Nandan Nilekani, co-founder, Infosys, and former chairperson, UIDAI” – Source: Mishra, Pankaj. Against the Grain: Lessons from the Outliers (p. 141). Penguin Random House India Private Limited. Kindle Edition.

- Skill development and personal growth: What is more important – the inner scorecard or the outer scorecard? What is more important – impressing the boss or ensuring that your toolkit is getting stronger each year?

The big question about how people behave is whether they’ve got an Inner Scorecard or an Outer Scorecard. It helps if you can be satisfied with an Inner Scorecard.”— Warren Buffett (source: https://fs.blog/the-inner-scorecard/).

Evolution has hardwired the desire for social status into all of us. That desire pushes us towards seeking external markers which tell the world that “I am a woman on the rise”. These markers can be precious stones & other accoutrements in our personal life and a corner office and a high-status job title in professional life. In contrast, in an entrepreneur’s life, these external markers of corporate success mean less because ultimately she has to build a profitable lasting franchise (rather than sit in the corner office and call herself the CEO).

In fact, even amongst India’s largest companies, those who rise to the top are often those who adopt the ‘inner scorecard’ approach to personal development.

The current CEO of Godrej Consumer, Sudhir Sitapati, published an outstanding book called “The CEO Factory” in 2022. At that point Sudhir was an Executive Director at HUL and in the book, Sudhir gives his view on why HUL is able to hire and groom outstanding talent which often demonstrates high levels of entrepreneurial acumen & drive:

“Framing insights requires three ingredients. The first is observation. You need to constantly read books, have conversations with interesting people and be consumer connected. The second is the ability to make lateral connections between disparate observations. This takes some conscious practice. And third, the ability to state the insight pithily.” – Sitapati, Sudhir. The CEO Factory: Management Lessons from Hindustan Unilever (p. 68). Juggernaut. Kindle Edition.

A decade ago, here is what Saurabh had to say about the promoter family of Berger Paints (a company whose share price has compounded 1000x since 1991):

“As per Forbes, the Dhingras are among India’s fifty richest families. And yet the Dhingras come across as different from the average Indian billionaire. They maintain a low profile and are rarely spotted in the press. They are neither in the business pages of the Economic Times nor on page 3 of ‘Bombay Times’. For a family of their stature, the office of the Dhingras in Delhi is a sparsely furnished, back-of-the-shopping-precinct affair in an unpretentious downmarket commercial complex adjoining Zamrudpur village. Berger itself is headquartered in Kolkata and runs its operations from a nondescript office building located at the low-profile end of Park Street. In my meetings over the past few years with the Dhingras, I have found them to be refreshingly grounded.” – The Unusual Billionaires (2016), pg. 87.

- Appetite for risk & failure: How much are you willing to challenge the established way of doing things? How willing are you to fall flat on your face in front of the whole world and suffer the consequences of failure?

Within the confines of a large company given the compensation and rank is deliberated upon and determined by committees, the external scorecard (and other external markers of hard work & achievement) carries a lot of weight. In such an environment, an executives risk-reward payoff distribution is usually skewed against risk taking. Failing conventionally is seen to be less of a problem as compared to trying something unconventional and falling flat on your face. Beyond the water cooler gossip, it is hard for the committees to promote such a “failure”.

In contrast, in an Indian entrepreneur’s life every step is characterized by risk taking. However, because there is no committee to pass judgement on the entrepreneur, she’s free to take as many risks as she wants provided she doesn’t blow up the enterprise (thereby rendering her colleagues redundant). Constant risk-taking and its close friend – failure – are therefore perpetual companions of the Indian entrepreneur. Failure & success are like summer & winter i.e. they are a routine part of an entrepreneur’s life and should not be a source of exultation or heartburn. In fact, failure is an essential milestone en route to acquiring skills & learning.

Harsh Mariwala, Founder & Chairperson of Marico, captures this aspect of entrepreneurship eloquently:

“…let me say that failure is part and parcel of an entrepreneur’s journey. And there is a saying: “Sometimes you win, sometimes you lose.” The same thing you can put differently: sometimes you win, sometimes you learn instead of losing! So any failure, any loss, is a great learning opportunity. And I think that’s happened to me many times because I’m not a management graduate, and neither has anybody mentored me in my whole journey or guided me. So I’ve been a self-learner. And often, you take some steps without realizing because you’ve not had an experience and nobody has guided you. My learnings have come from exploring some uncharted territory and later realizing that I made a mistake.

So my first learning was in the initial part of my journey when I was less than thirty years old. And at that time, we wanted to get into some new products and had identified an opportunity. But because we didn’t want to add to our overheads, we took some shortcuts in terms of product formulation. We tried to do it in-house without knowing what it meant. And that backfired. We also didn’t invest heavily in quality systems. And the new product had some quality assurance problems…

…each failure has its own set of learnings. And today, all I can say is that every entrepreneur goes through these failures. We should not be afraid of failures, and should go on experimenting and prototyping. And it’s okay to fail.’” – Source: Mishra, Pankaj. Against the Grain: Lessons from the Outliers (p. 12). Penguin Random House India Private Limited. Kindle Edition.

- Time horizon: Am I working within a 1-2-3-year capital budgeting & strategy timetable OR am I playing an infinite game with much longer time horizons? Am I trying to make a profit OR am I trying to build an institution which will outlive me?

In corporate life in India, most CEOs seldom last more than 3-4 years. If they fail to deliver the profit compounding sought by the promoter and/or the stock market, they have to fall on their axe. And if they do an exceedingly good job, they are usually headhunted for a better gig elsewhere (usually in a Private Equity owned firm or in a global role). In any event, most CEOs of large Indian companies are on their way out in 3-4 years.

This 3–4-year cycle therefore ends up characterizing the planning, strategizing and capital budgeting process of large Indian companies. That in turn means that other executives in the corporate construct also have to plan their careers around such a “World Cup” cycle. Naturally, therefore given the finite time horizons, the scope of experimentation, risk-taking and upskilling is limited. All that matters is hitting the targets and getting promoted within the World Cup cycle.

An entrepreneur’s life does not have a World Cup cycle. If she’s ambitious and is seeking to build a company which will disrupt an industry and cement her legacy, she’s thinking in terms of decades, not World Cup cycles. In fact, India’s most valuable conglomerate (by a country mile) was created by entrepreneur who thought in terms of centuries:

“Jamsetji Tata was born in 1839. He started his partnership firm Tata and Sons in 1868. The company, Tata Sons Ltd, was incorporated in 1917 and took over the business of Tata and Sons. Today, more than 150 years later, this business that is now broadly referred to as the Tata Group, continues to grow and flourish. In fact, Tata has been the pre-eminent business house in India for several decades, a position it continues to occupy until today. The thought leadership of Jamsetji and his successors has stood the test of time and has proven its enduring quality through all these years of industrial and economic development in India. The options chosen by the leadership, the strategies it adopted, and its string of commercial actions still bear vibrancy and relevance—and they are based on human values.”- Bhat, Harish; Gopalakrishnan, R. Jamsetji Tata: Powerful learnings for corporate success (pp. 9-10). Penguin Random House India Private Limited. Kindle Edition.

Investment implications

Judging by Income Tax returns, around 40mn Indians earnings between Rs. 5 lakhs – 1 crore per annum constitute the Middle Class insofar as they are the middle 50% of India’s income distribution (of Income Taxpayers). Income Tax data for the last decade shows that opportunities for financial advancement for these group have becoming progressively scarce. In parallel, data from Naukri shows that employment opportunities for this group are also dwindling. In such a situation, this class of Indians will have to pivot towards entrepreneurial opportunities.

Whilst dramatic improvements in physical & digital infrastructure bode well for India’s budding entrepreneurs, the pivot from salaried employment in large companies to running small-midsized enterprises is not easy. In particular, the new skillsets that the Middle Class needs to acquire – around risk-taking, around relentless reskilling & learning, around embracing failure, around long-time horizons – will take time to seep in. In this transition period therefore it is more likely than not that we will see an extended consumption slowdown in India as the Middle Class regroups, rethinks its priorities in life and reskills.

The above material is neither investment research, nor investment advice. Marcellus does not seek payment for or business from this material/email in any shape or form. Marcellus Investment Managers Private Limited (“Marcellus”) is regulated by the Securities and Exchange Board of India (“SEBI”) as a provider of Portfolio Management Services. Marcellus is also a US Securities & Exchange Commission (“US SEC”) registered Investment Advisor. No content of this publication including the performance related information is verified by SEBI or US SEC. If any recipient or reader of this material is based outside India and USA, please note that Marcellus may not be regulated in such jurisdiction and this material is not a solicitation to use Marcellus’s services. All recipients of this material must before dealing and or transacting in any of the products and services referred to in this material must make their own investigation, seek appropriate professional advice. This communication is confidential and privileged and is directed to and for the use of the addressee only. The recipient, if not the addressee, should not use this material if erroneously received, and access and use of this material in any manner by anyone other than the addressee is unauthorized. If you are not the intended recipient, please notify the sender by return email and immediately destroy all copies of this message and any attachments and delete it from your computer system, permanently. No liability whatsoever is assumed by Marcellus as a result of the recipient or any other person relying upon the opinion unless otherwise agreed in writing. The recipient acknowledges that Marcellus may be unable to exercise control or ensure or guarantee the integrity of the text of the material/email message and the text is not warranted as to its completeness and accuracy. The material, names and branding of the investment style do not provide any impression or a claim that these products/strategies achieve the respective objectives. Further, past performance is not indicative of future results. Marcellus and/or its associates, the authors of this material (including their relatives) may have financial interest by way of investments in the companies covered in this material. Marcellus does not receive compensation from the companies for their coverage in this material. Marcellus does not provide any market making service to any company covered in this material. In the past 12 months, Marcellus and its associates have never i) managed or co-managed any public offering of securities; ii) have not offered investment banking or merchant banking or brokerage services; or iii) have received any compensation or other benefits from the company or third party in connection with this coverage. Authors of this material have never served the companies in a capacity of a director, officer, or an employee. This material may contain confidential or proprietary information and user shall take prior written consent from Marcellus before any reproduction in any form.