Marcellus’ Global Compounders Portfolio (GCP) strategically invests in 25-35 deeply moated global companies aligned with megatrends which aid the delivery of mid-to-high teens compounding of free cash flow/earnings.

To identify such compounders, one of the markers that we look for is the amount of value companies are able to capture from broader opportunities. This is all the more important given slow underlying economic growth in the developed world, which means that companies need to maximise the limited opportunities that are available. In this newsletter, we try and illustrate this by looking at two companies which have generated massive value from the China growth story over the past two decades. Both are near optimal examples of how companies from the rest of the world leveraged the sourcing opportunities that China offered (Apple) and the consumer demand it created in China (Hermès). These two companies have generated substantially more opportunity from this than their suppliers or the broader Chinese consumer market did.

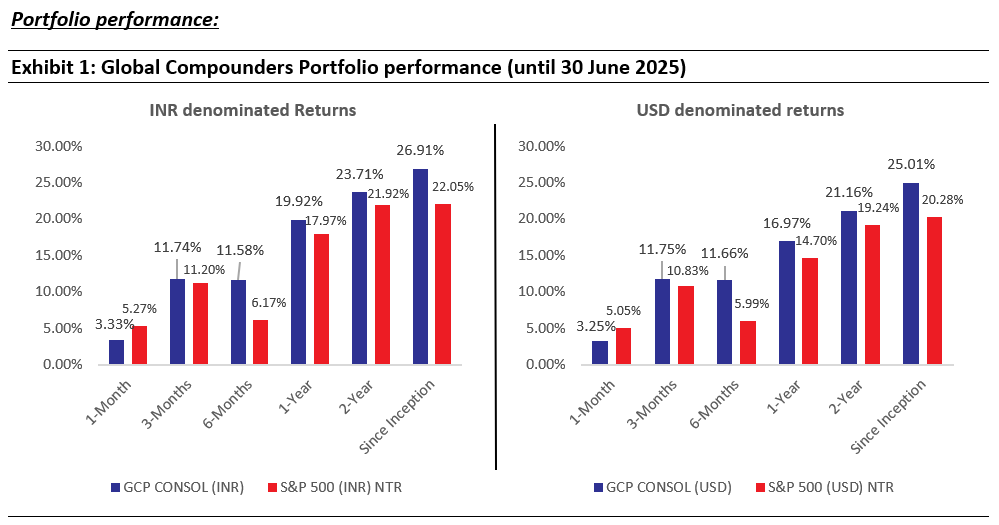

|

Marcellus performance data is shown gross of taxes and net of fees & expenses charged till 30th June 2025 on client account. Returns for time periods above 1-year are annualised while returns for time periods 1-year and lower are absolute. Marcellus’ GCP USD returns are converted into INR using USD:INR exchange rate from RBI – Link for the reference Source: Marcellus Investment Managers Note: * Since Inception performance calculated from 31st Oct 2022. The inception date is 31st October 2022, being the next business day after the account got funded on 28th October 2022. S&P 500 net total return is calculated by considering both capital appreciation and dividend payouts. The calculation or presentation of performance results in this publication has NOT been approved or reviewed by the IFSCA or US SEC. Performance is the combined performance of RI and NRI strategies. |

|

Marcellus’ GCP is through Separately Managed Accounts (i.e., SMAs, just like a PMS) via GIFT City (regulated by IFSCA) Permissible Accredited Investors* can now invests in GCP Strategy with minimum ticket size USD 25,000 and non-accredited investors, Invest in with a minimum investment amount of USD 75,000. *Accredited Investors shall qualify eligible criteria as defined under IFSCA-IF-10PR/1/2023-Capital Markets dated January 25, 2024. |

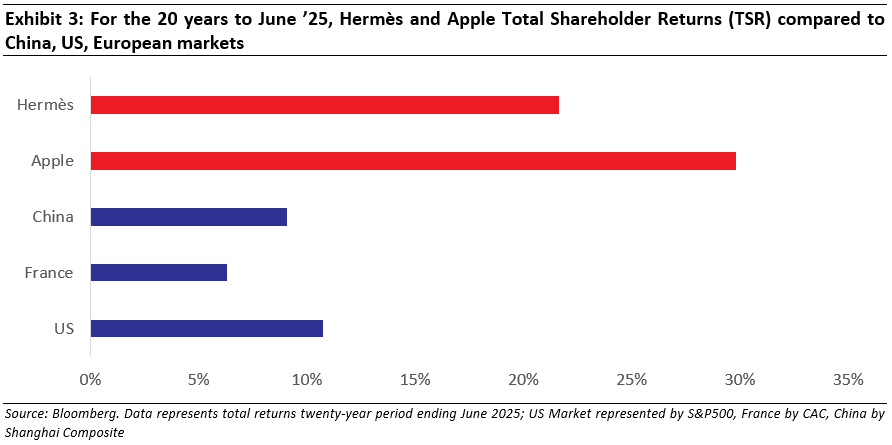

A question we often hear is: Why invest in developed market equities—like those in the US or Europe—when faster GDP growth is taking place in emerging markets such as China or India? At first glance, the logic seems straightforward: invest where the growth is. But the relationship between economic growth and equity returns is far more nuanced.

In fact, academic research (link) has shown that there is little to no long-term correlation between a country’s GDP growth and its stock market returns. In other words, fast-growing economies don’t necessarily produce the best-performing stocks.

Rather than rely on theory alone, we wanted to explore this idea through real-world examples. Because what ultimately matters isn’t where growth is occurring but who is capturing the value from that growth. And time and again, it’s developed market companies—especially global leaders—that have proven most effective at doing so.

Let’s take a closer look.

Value Capture as a Marker of Greatness

Developed market companies often operate in mature economies with limited topline growth. In such environments, value creation requires identifying and scaling profitable opportunities beyond domestic markets. The ability to capture disproportionate value from global growth—especially from fast-growing economies—becomes a defining trait.

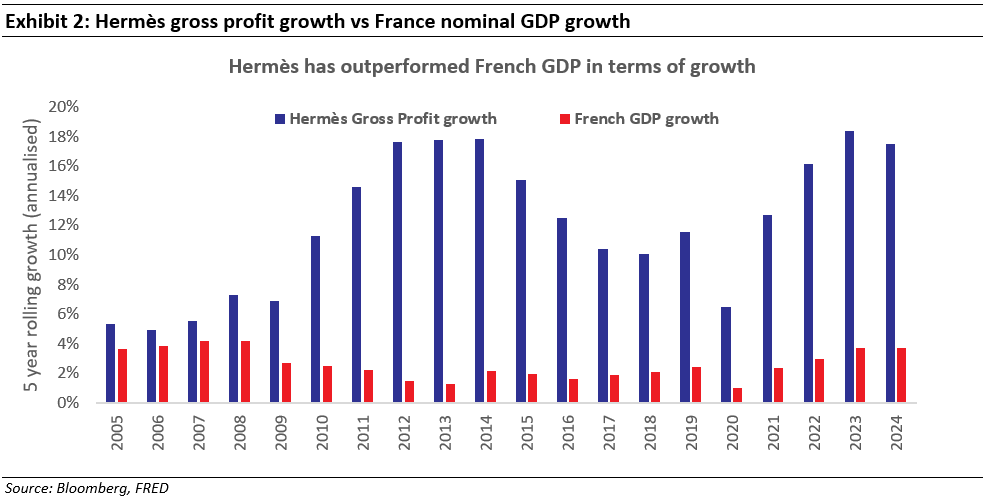

Hermès is a textbook example. While France’s nominal GDP has grown steadily but modestly, Hermès has consistently outpaced it across any rolling five-year period in recent decades. The company’s ability to capture demand from global affluent consumers—especially in Asia—has driven this outperformance.

China: A Case Study in Global Value Creation

China’s explosive growth over the last three decades has created immense opportunities for companies worldwide. Broadly, these have come through two channels:

(a) Manufacturing in China, and (b) Selling to Chinese consumers.

The following case studies of Apple and Hermès show how Western companies—despite being headquartered in slow-growing economies—captured disproportionate value from China’s rise, far more so than many Chinese firms themselves

Apple: Making in China, Winning Globally

Apple’s relationship with China is one of the most powerful examples of how a developed market company can capture the lion’s share of value from an emerging market’s economic boom.

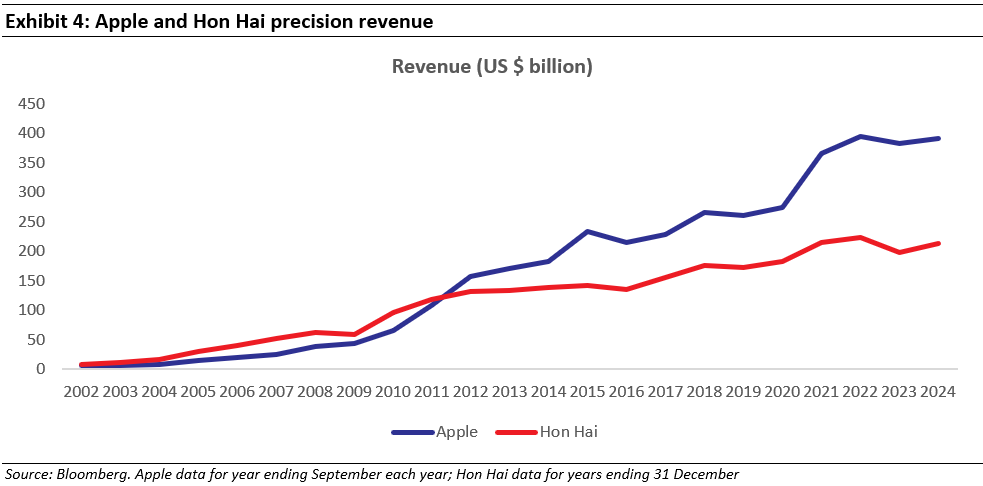

Unlike many of its peers, Apple was a relatively late entrant to the “Make in China” movement. In the late 1990s, large PC makers like Dell had already built extensive supply chains across Asia. Apple’s shift to China began in earnest only in 2002, when it entered a manufacturing partnership with Foxconn (Hon Hai Precision) to assemble iPods and Macs. This relationship soon scaled up dramatically with the introduction of the iPhone in 2007 and later the iPad in 2010s.

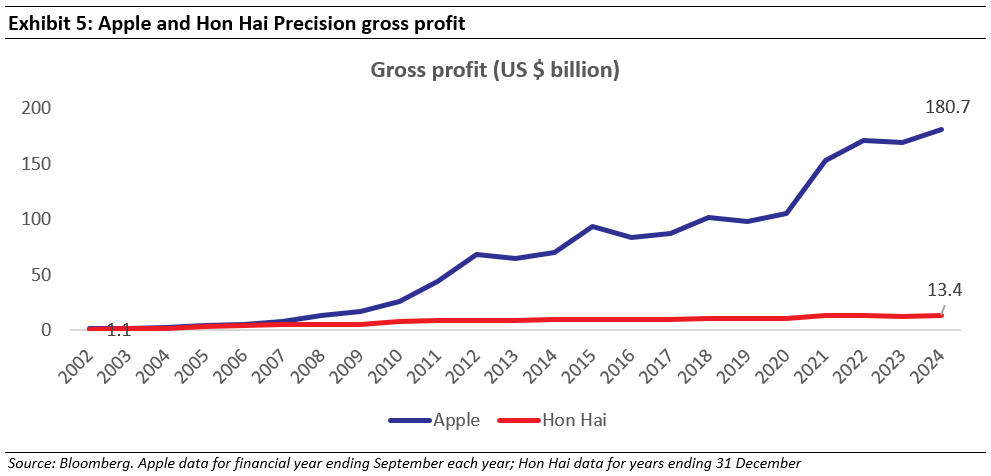

From 2002 to around 2012, Apple and Hon Hai grew in tandem. Their revenues broadly tracked each other, reflecting the exponential rise of the iPhone franchise and the growing scale of Foxconn’s operations to support Apple’s hardware assembly needs.

However, beneath this similarity in revenues was a sharp divergence in value capture. Foxconn’s gross margins declined from ~14.7% in 2002 to just ~6.4% by 2012, even as its revenues soared. It was expanding, hiring, and producing at massive scale—but not capturing much incremental economic value. Apple, on the other hand, began to separate itself sharply in terms of profitability. Its gross profits surged far ahead of Foxconn’s. Despite employing fewer than 200,000 people—compared to Foxconn’s workforce of close to a million supporting the Apple ecosystem. This reflects the classical value capture that comes from significantly superior pricing power. In the years since, this gap has continued to widen as Apple added other levers. This widening gap reflects a fundamental truth about modern global capitalism: owning the product, the brand, the customer relationship, and the IP is far more lucrative than executing the manufacturing

What the data doesn’t fully capture are two critical elements behind Apple’s success in China:

First, Apple didn’t treat Chinese manufacturing merely as a cost-cutting exercise. Instead, it viewed China as a strategic partner—leveraging the country’s unique combination of scale, skilled labor, and manufacturing sophistication to differentiate its products. Rather than chasing the lowest cost, Apple focused on building devices of unmatched quality and complexity.

To achieve this, Apple invested deeply in its supplier ecosystem. It worked closely with tier-2 and tier-3 suppliers, helping them upgrade capabilities through on-the-ground collaboration, equipment support, and training. This tight integration enabled Apple to push the boundaries of product design with confidence that manufacturing could keep pace. It also helped navigate the risks around reliability of timelines and quality control that others have had to work with. The result was a steady cadence of groundbreaking products—from the iPod and iPhone to the iPad, Apple Watch, and AirPods—delivered on a demanding annual launch cycle. This kind of scale, precision, and reliability would have been impossible without the capabilities Apple helped develop within China.

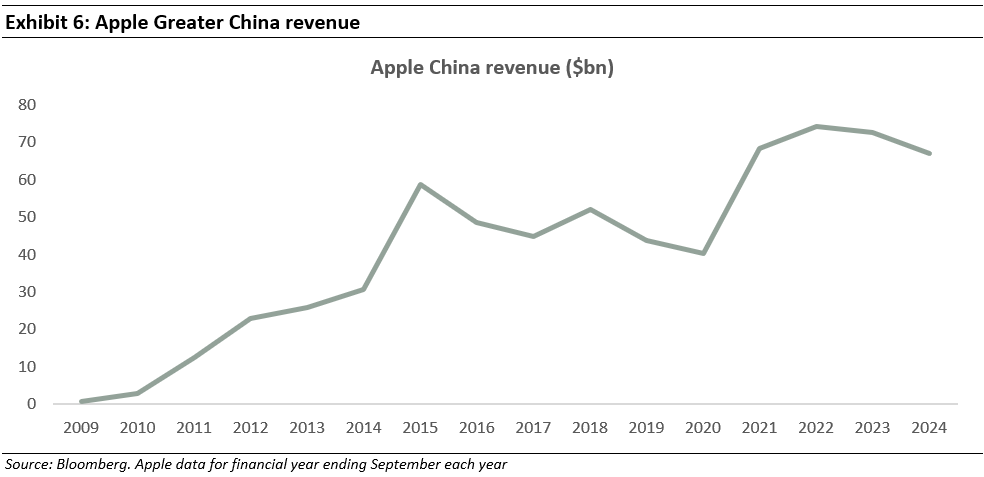

Second, Apple navigated China’s complex regulatory and political environment with exceptional dexterity. In the early 2010s, while many foreign tech companies struggled or were forced into joint ventures, Apple remained one of the few able to operate independently and retain control over its ecosystem. It managed to comply with Chinese regulations—particularly around the App Store—while still capturing a dominant share of the premium smartphone market. As a result, its Greater China revenue scaled from under $1 billion in 2009 to over $58 billion by 2015, far outpacing peers.

In summary, Apple’s China playbook was not about chasing cheap labor. It was about leveraging China’s manufacturing sophistication to scale quality and complexity, while retaining full control over branding, product experience, and customer monetization. It created a value chain in which Apple captured the vast majority of economic surplus—even as its partners shouldered the labor and capex.

In doing so, Apple built a trillion-dollar market cap business on the back of Chinese growth—far outpacing the value created by its own suppliers in the region. This is a prime example of how developed market companies can, and often do, capture the most profitable parts of emerging market growth—and why investing in the right developed market businesses can be an effective way of benefiting from emerging market economic opportunities without buying emerging market equities directly.

Hermès and selling in China

While Apple exemplifies how a developed market company can make in China and win globally, Hermès demonstrates how the right to sell into China—especially to the top end of the consumer market—can be just as powerful a value creation engine.

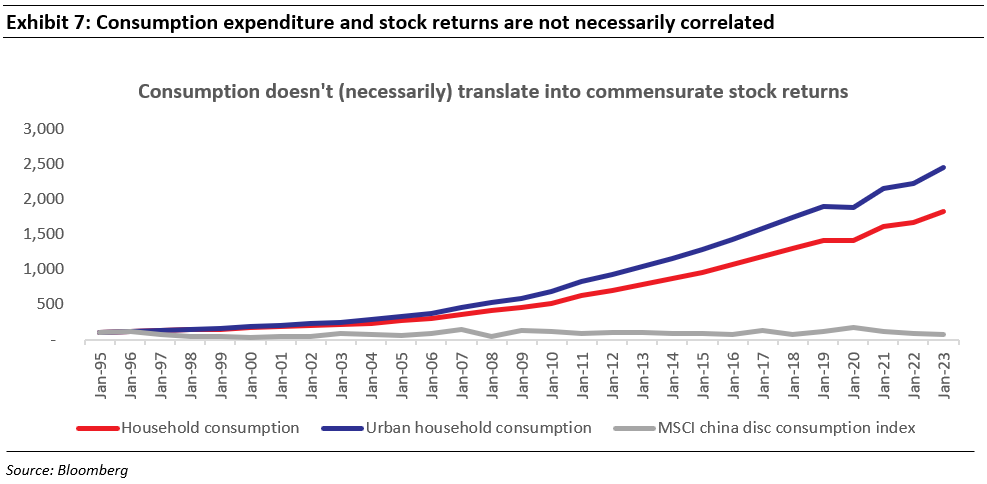

Over the past three decades, China has seen an extraordinary rise in household consumption. Since the early 1990s, total household spending has grown more than 18x, with urban household consumption increasing nearly 25x. This massive rise in domestic demand turned China into the largest or second-largest market globally for many consumer categories—including luxury goods.

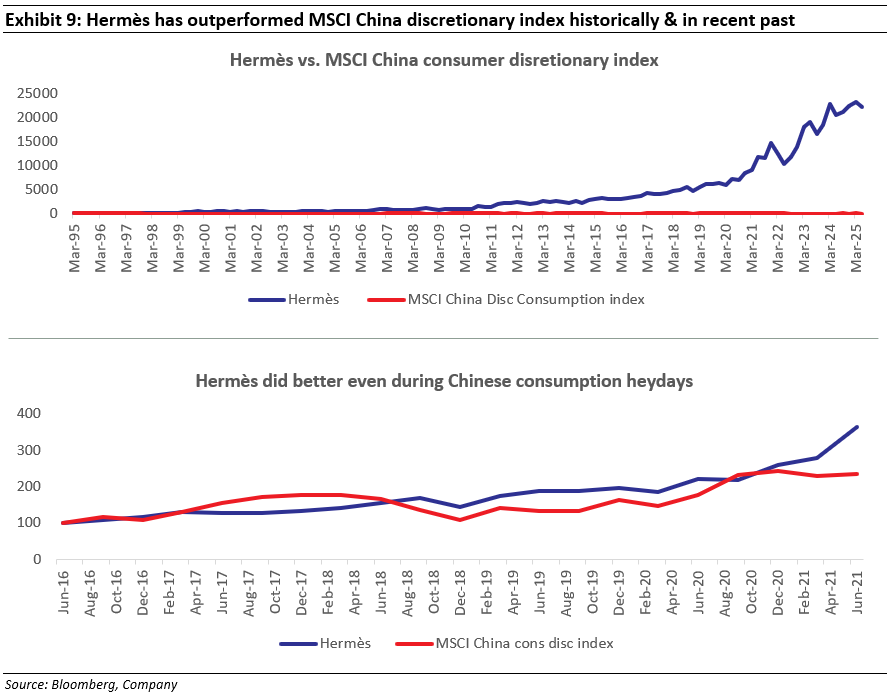

And yet, rising consumption alone hasn’t translated into strong stock market returns for most domestic consumer companies. The MSCI China Consumer Discretionary Index has largely gone sideways over the last 25+ years. However, much like the myth of GDP growth & stock market returns correlation (discussed briefly in our May’24 newsletter ), this disconnect reflects the reality that growth in spending does not automatically equate to value capture—especially when companies lack pricing power, brand equity, or customer loyalty.

This is where Hermès stands out

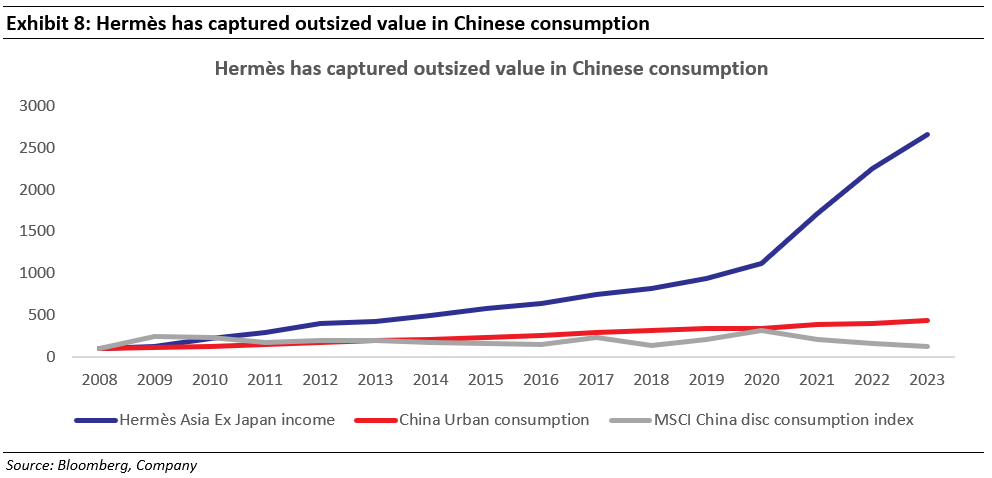

While most local consumer firms have been caught in cycles of promotional pricing, brand fatigue, and rising competition, Hermès has consistently focused on the topmost sliver of Chinese consumers—those who value exclusivity, craftsmanship, and timelessness. This focus on the ultra-premium customer, coupled with supply discipline and a refusal to chase volume, allowed Hermès to capture the most profitable segment of China’s consumption boom.

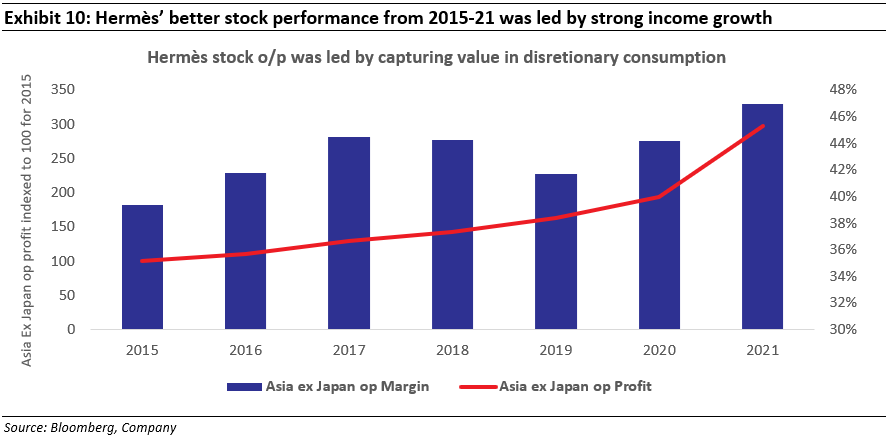

As a result, Hermès’ revenue from Asia ex-Japan (a region dominated by China) has grown far faster than the broader Chinese urban consumption figures, and significantly outpaced local discretionary peers. Operating income from the region has scaled steadily, supported by robust margins—often north of 40% at the operating level and ~70% in gross margin.

A long-term comparison of Hermès’ share price performance against the MSCI China Consumer Discretionary Index reveals a stark divergence in shareholder returns. Despite both being exposed to the same broad consumption boom in China, the outcomes have been dramatically different.

Even during the post-crisis recovery from 2015 to 2021—when China’s consumer discretionary index rebounded by ~2.5x—Hermès still delivered significantly stronger returns, underpinned by sustained revenue growth and margin expansion.

What drove this outperformance was not just topline growth, but Hermès’ ability to convert demand into high-quality, profitable income. During this period, the company materially increased its operating income from China, aided by rising margins—a direct reflection of its pricing power and the strength of its brand.

This highlights a critical point: $100 (or ¥100) of consumer spending does not translate equally across companies. Businesses like Hermès, with deeply entrenched brand equity and a loyal, high-end customer base, are uniquely positioned to extract maximum value from each unit of consumption. With gross margins nearing 70%, Hermès stands in sharp contrast to the many consumer firms battling for attention through discounts and promotions in an increasingly crowded, price-sensitive market. The strong brand and discipline that Hermès exhibited helped it avoid the price competition risks other consumer businesses operating in China faced.

|

In summary, Hermès’ success in China underscores the power of global brand leadership, customer intimacy, and value discipline. In conclusion, we think that the experiences of Apple and Hermès offer a powerful answer to the question: Why invest in developed markets when emerging economies are growing faster? Both companies are headquartered in mature, slower-growing economies—but they have been among the most effective at monetizing the growth tailwinds of emerging markets. Apple used China not just for cost-efficient manufacturing, but as a strategic partner in scaling innovation, while Hermès tapped into rising Chinese affluence with discipline, brand strength, and an unwavering focus on quality over quantity. In both cases, these companies didn’t merely ride the wave of emerging market growth—they owned the most profitable parts of it. Their value creation far outstripped that of local firms operating in the same environment, many of whom lacked the pricing power, brand loyalty, or business model resilience needed to convert demand into durable shareholder returns. Over the last decade, Apples and Hermes have compounded shareholders’ total return at an annualised rate of 25.7% and 26.7% respectively (in INR terms). A carefully curated portfolio of global, developed market champions—those with the capability to access and extract value from faster-growing parts of the world—has the potential to be a superior investment strategy. Such a portfolio can benefit from emerging market economic opportunities without needing to invest in volatile emerging market equities directly. This extra growth can potentially help outperform slower growing developed markets. It’s not where the growth is happening that matters most—it’s who is best positioned to capture and convert that growth into shareholder value. |

|

If you want to read our other published material, please visit https://marcellus.in/ |