OVERVIEW

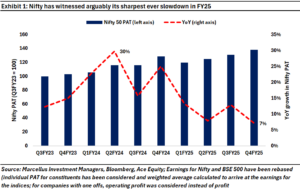

From Diwali 2023 onwards, Indian companies’ earnings growth has decelerated at a rapid rate. Underpinning this deceleration is a sharp conk-off in consumption growth, long the mainstay of the Indian economy. Key drivers of this consumption downturn are a sharp deceleration in white collar job creation alongside a reduction in real wages for white collar workers over the past eight years. Both of these are side-effects of the rise of AI & automation in India’s factories and offices.

“We document that between 50% and 70% of changes in the U.S. wage structure over the last four decades are accounted for by relative wage declines of worker groups specialized in routine tasks in industries experiencing rapid automation….Automation technologies expand the set of tasks performed by capital, displacing certain worker groups from jobs for which they have comparative advantage. This framework yields a simple equation linking wage changes of a demographic group to the task displacement it experiences. We report robust evidence in favor of this relationship and show that regression models incorporating task displacement explain much of the changes in education wage differentials between 1980 and 2016.” – Daron Acemoglu & Pascual Restrepo, Econometrica, Vol. 90, No. 5, September 2022

What is driving the earnings slowdown in India?

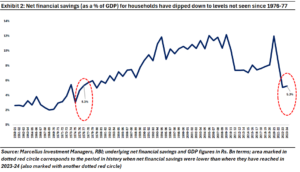

During 2020 and 2021, thanks to the ravages of Covid, most Indians were locked-down at home for the best part of two years. When one is sitting at home for months on end, there is only so much money one can spend on food, online shopping & entertainment. As a result, Indian families saved large sums of money over this two-year period. In fact, as per the RBI, India’s net household financial savings touched an all-time high of 12% of GDP during this period.

Then around Diwali 2021, Indians emerged out of their homes as the Covid lockdowns faded away. With their stored-up savings from the Covid years, Indian households went on a wild spending frenzy aka “revenge spending”. Not only were shopping malls and department stores full, but online spending growth was also strong in this post-Covid period.

From Diwali 2021 until Diwali 2023, Indian households spent, partied and holidayed merrily. For example, demand for SUVs grew by 30% YoY (by volume) in FY23 whilst sales of apartments rose by 44% YoY (by value). Hotels ran out of rooms and jacked up their rates. Indian Hotels (the owners of the ‘Taj’ and ‘Vivanta’ brands) saw its operating margins approach an all-time high of 30%.

By the end of 2023 however Indian households began running out of savings. You can see this very visibly in the RBI’s net household savings data – see chart below.

By the time Holi rolled in 2024, household savings in India were approaching a 50 year low i.e., FY24 household savings (as a % of GDP) was at the same level as it was after the Emergency ended, in 1977.

Given that consumption accounts for 60% of GDP, the slowdown in consumption that began manifesting itself around Diwali 2023 naturally caused a conk-off in corporate earnings in Q3 FY24 i.e., the quarter ending December 2023.

Nearly two years on from the beginning of this slowdown in consumption and corporate profit growth, there is no sign of an upturn in this cycle. CEOs and policymakers are worried and bewildered. The RBI has cut interest rates repeatedly and flooded the financial system in Mumbai with money. And yet credit growth is actually falling rather than rising. So what is going on? Why is this consumption slowdown so elongated?

Structural and the cyclical factors in play in the job market

White collar jobs have a disproportionate impact on India’s economy because each such employee creates another 2-3 jobs directly (e.g. cook, driver, cleaner) and another 2-3 jobs indirectly (e.g. the security guard in your housing complex and in your office, waiters & hotels managers, shop assistants & store managers, stewards & pilots, etc). As a result, the 40 million or so middle-class Indians (using the number of Indians who report annual incomes between Rs 5 lakhs – 1 crore in their Income Tax returns) generate employment for another ~200 million Indians.

Whilst there are a variety of metrics available in India to measure employment, most notably the Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS), it does not accurately try to capture the issue of white-collar job creation in India simply because it considers self-employment as legitimate employment. As a result, this sort of survey data makes it difficult to figure out what exactly is happening to white collar employment in India.

In this regard, we believe, Naukri Jobspeak Index that Naukri, India’s largest employment classifieds website, publishes every month, is a better indicator for measuring white collar job demand and creation in India.

As Naukri’s website explains, the Naukri Jobspeak Index is a monthly index that represents the state of Indian job market and hiring activity based on new job listings and recruiter searches on Naukri’s resume database. Naukri started publishing this index as far back as in 2008 and has been publishing it at an all-India aggregate level as well as for different sectors.

In the decade ending in FY20, white collar job openings in India grew at a scorching pace of 11% per annum implying that every six years, the number of white-collar jobs in India was doubling. In sectors like IT/Software Services the growth was even more dramatic – 16% per annum (implying a doubling of jobs every four years).

From FY20 onwards however, the picture changed dramatically. Job creation growth has slowed down to 3% per annum (implying a doubling of jobs every 24 years). Given that India’s population is growing at 1% per annum and the number of students graduating from university is growing faster than that (thanks to rising enrolment rates for university education), on a per capita basis the post FY20 era has basically seen a stagnation in job availability. In fact, as the chart above shows, the post-Covid slowdown in jobs has hit some of those very sectors which were considered the backbone of India’s middle class employment dream – the software, IT, and retail sectors.

So why is this happening now? Our research suggests that there are cyclical and structural

- Unwinding the post-Covid hiring spree: As demand surged during and immediately post-Covid, companies across the world went on a hiring spree. This was especially true for the IT sector (see the spike in the chart above) where top listed Indian IT Services companies hired close to 8 lakh workers between 2020 –22 [source: NASSCOM] in the hope that the everything everywhere will go digital after Covid. Then as demand moderated from 2024 onwards, employers realised that they didn’t need so many workers. Now, across the world, large companies – including some of the world’s most profitable companies such as Microsoft, Google and TCS (who have financial reserves more than most sovereigns) – are laying off thousands of skilled workers. This is obviously pro-cyclical behaviour and in the next demand upturn, we won’t be surprised to see the same companies hiring again.

- AI is replacing humans: The second factor, which is more structural, is the replacing of human employees with AI and automation. In highly competitive free market economies like USA and India, companies are now looking to boost their profit margins by replacing human workers with AI. Google has said that a quarter of its coding is now done by bots (source: Times of India ). Investments firms like Marcellus are also finding that AI can produce high quality research comparable sometimes in quality to what an analyst with a decade of experience would produce.

In 2003, Richard Murnane, David Autor, and Frank Levy wrote a brilliant paper saying that routine and non-cognitive tasks are the ones most likely to be automated and this, they said, has the potential to displace a lot of the workers who are traditionally considered to part of the middle class (source: https://economics.mit.edu/sites/default/files/publications/the%20skill%20content%202003.pdf).

Whilst Murnane, Autor, and Levy had formed the hypothesis in the context of the US economy and in the age of computerization, their learnings are applicable to India and in the age of AI to even non-routine, white collar and middle-class jobs.

In fact, many of the largest employers in India are going on record and saying that they are likely to trim their employee base and leverage AI to get more done at lower cost. For example, India’s largest IT sector employer, Tata Consultancy Services, said in July 2025 that is planning to reduce its workforce by 2% (~12,000 employees). TCS’s CEO K Krithivasan says that “We have been calling out new technologies, particularly AI and operating model changes. The ways of working are changing. We need to be future-ready and agile. We have been deploying AI at scale and evaluating skills we will be requiring for the future.”

Similarly, the CEO of HCL Tech, C Vijayakumar, said on 24th February 2025 that they are going to target double the revenue with just half the labour force leveraging AI and technology.

Salaries are not keeping pace with the cost of living

If workers are being displaced by technology then economic theory says that two opposing effects will kick-in with respect to wages:

a. the demand for workers will drop (as seen in Exhibit 3) and this in turn should depress wages; and

b. the workers who are in employment should get paid more given that they are now using technology to produce more for their employers (e.g. the coders who are retaining their jobs in TCS will be productive due to AI and will presumably earn more).

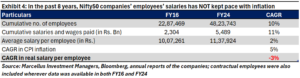

Which of these effects will dominate is hard to say on theoretical grounds alone. So let’s turn to data to inform our judgement on this key issue. To be precise, let’s use data from India’s fifty largest listed companies. If companies in India are going to use AI & automation to reduce their workforce and drive efficiency gains, it is in the country’s largest companies where this effect will show up first.

We looked at the average income earned by employees of the Nifty 50 companies as they stood on 31st March 2024 and then calculated how this average income [for the same set of 50 companies] has increased in the preceding 8 years (i.e., from FY16). We also compared it with average CPI inflation during this period to understand if salaries kept pace with the cost of living.

As it turns out, average incomes have NOT kept pace with the cost of living as far as the Nifty 50 companies are concerned. In other words, if someone was just relying on their salary increments in the last 8 years, far from being able to earn and save money for the future, their salaries won’t have been able to keep up even with price of food (see table below).

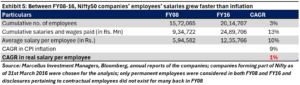

To see if this had also been the case in the earlier part of the 21st century, we did the same analysis for Nifty companies as they stood on 31st March 2016 (FY16) going back to FY08 [for the same set of 50 companies]. It turns out that employee salaries were keeping pace at least with inflation back then (see table below). In other words, people employed by these companies were not losing money in real terms and were able to save (albeit a tiny amount, it was still positive).

Nandita Rajhansa and Saurabh Mukherjea work for Marcellus Investment Managers (www.marcellus.in). The views and opinions expressed in this material are those of the writers/authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy. This material is for informational and educational purposes only and should not be considered as financial, investment, or other professional advice. The inclusion of any book does not imply endorsement or recommendation by the writers or the publisher of this material.

The above material is neither investment research, nor investment advice. Info Edge (Naukri), Microsoft, Alphabet (Google), and HCL Tech form part of Marcellus’ Portfolios. We as Marcellus, our immediate relatives and our clients may have interest and stakes in the mentioned stocks. The stocks mentioned are for educational purposes only and not recommendatory. Marcellus does not seek payment for or business from this material/email in any shape or form. Marcellus Investment Managers Private Limited (“Marcellus”) is regulated by the Securities and Exchange Board of India (“SEBI”) as a provider of Portfolio Management Services. Marcellus is also a US Securities & Exchange Commission (“US SEC”) registered Investment Advisor. No content of this publication including the performance related information is verified by SEBI or US SEC. If any recipient or reader of this material is based outside India and USA, please note that Marcellus may not be regulated in such jurisdiction and this material is not a solicitation to use Marcellus’s services. All recipients of this material must before dealing and or transacting in any of the products and services referred to in this material must make their own investigation, seek appropriate professional advice. This communication is confidential and privileged and is directed to and for the use of the addressee only. The recipient, if not the addressee, should not use this material if erroneously received, and access and use of this material in any manner by anyone other than the addressee is unauthorized. If you are not the intended recipient, please notify the sender by return email and immediately destroy all copies of this message and any attachments and delete it from your computer system, permanently. No liability whatsoever is assumed by Marcellus as a result of the recipient or any other person relying upon the opinion unless otherwise agreed in writing. The recipient acknowledges that Marcellus may be unable to exercise control or ensure or guarantee the integrity of the text of the material/email message and the text is not warranted as to its completeness and accuracy. The material, names and branding of the investment style do not provide any impression or a claim that these products/strategies achieve the respective objectives. Further, past performance is not indicative of future results. Marcellus and/or its associates, the authors of this material (including their relatives) may have financial interest by way of investments in the companies covered in this material. Marcellus does not receive compensation from the companies for their coverage in this material. Marcellus does not provide any market making service to any company covered in this material. In the past 12 months, Marcellus and its associates have never i) managed or co-managed any public offering of securities; ii) have not offered investment banking or merchant banking or brokerage services; or iii) have received any compensation or other benefits from the company or third party in connection with this coverage. Authors of this material have never served the companies in a capacity of a director, officer, or an employee. This material may contain confidential or proprietary information and user shall take prior written consent from Marcellus before any reproduction in any form.