In this newsletter, we discuss the so called “low-risk” anomaly which posits that high beta (or high risk) stocks underperform low beta or (low risk stocks) over the long term i.e. there is NO extra return to be earned from owning riskier stocks. We show that this low-risk anomaly works in India as well. In this context, MeritorQ’s fundamentals-focused, systematic and value-conscious approach offers a better alternative to harvest the low-risk premium than strategies based solely on price-based measures of risk.

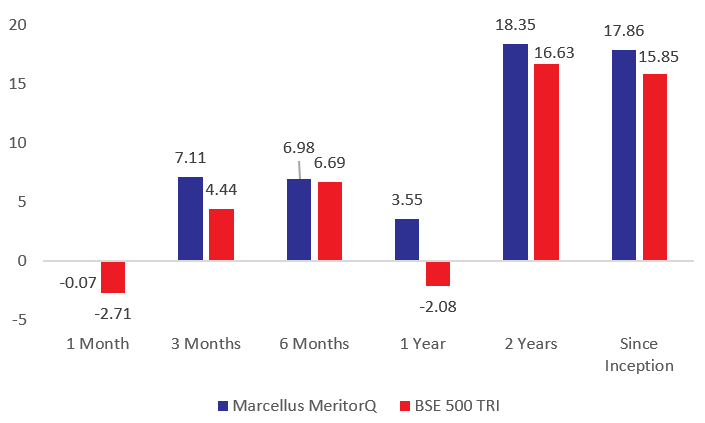

Portfolio Performance in %:

For Relative performance of particular Investment Approach to other Portfolio Managers within the selected strategy, please refer this link

Source: Marcellus Investment Managers. Note: (i) Portfolio inception date is November 15, 2022. (ii) Returns as of Jul 31, 2025. (iii) Performance data is net of fixed fees and expenses charged on a quarterly basis, the effect of the same has been incorporated up to June 30, 2025. Performance data is not verified either by Securities and Exchange Board of India or U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. (iv) Total returns index considered for BSE500 above.

“The essence of investment management is the management of risks, not the management of returns”

– Bejamin Graham

One of the most persistent and counterintuitive patterns in investing is the low beta or low risk anomaly—the empirical observation that lower-risk stocks, as measured by price volatility or beta, tend to deliver superior long-term returns compared to their higher-risk (or higher beta) peers. This means that there is NO extra return to be had for taking on extra risk.

The low risk anomaly flies in the face of traditional finance theory, which suggests a positive relationship between risk and return, typically using short-term price volatility, or ‘beta’, as a proxy for risk.

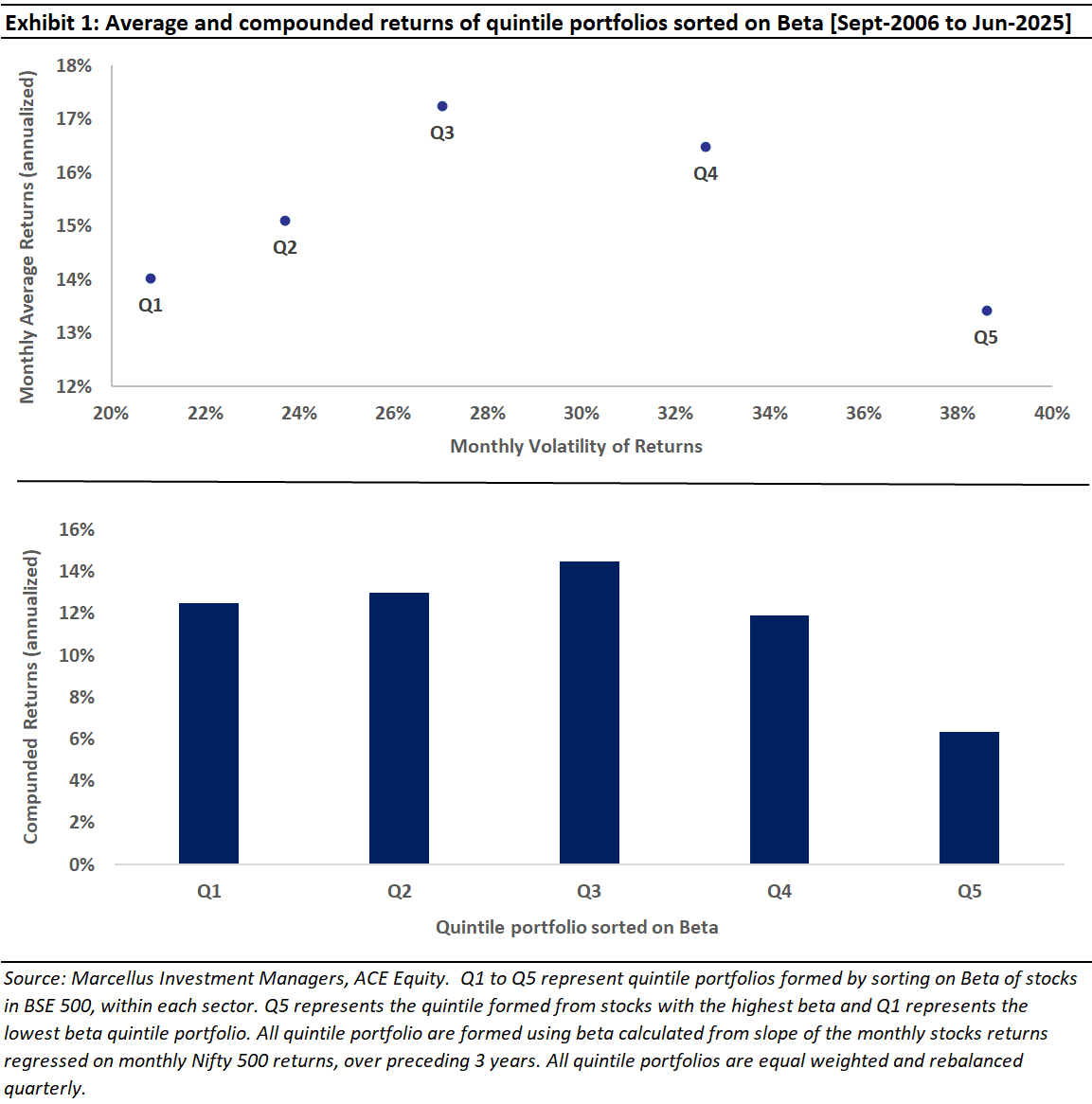

Exhibit 1 shows that this low-risk effect applies to Indian equities as well over last 19 years. For this analysis, we divided BSE 500 companies into 5 equal buckets (or quintiles), within each sector and then sorted the buckets on beta (as measured against the Nifty 500 Index). Hence, all 5 buckets or quintile portfolios have equal representation of companies in each sector to ensure that this low beta or low risk effect is simply not due to the sector bias of being overweight traditional defensive sectors like FMCG, Utilities, healthcare versus more cyclical ones.

Irrespective of whether one considers simple average or compounded returns, the higher beta quintiles (Q4 and Q5) clearly underperform their relatively lower beta counterparts. Lower beta portfolios (Q1 and Q2) show relatively better compounded returns than average returns. This should not come as a surprise, as any investor who has faced significant price declines knows, average returns can be drastically different from compounded returns. For instance, an investment alternating between -30% and +30% annual returns would have an average return of 0%, yet an investor would have lost nearly 40% of their starting wealth over ten years due to the devastating impact of compounding large losses.

This low risk or low beta anomaly has been documented in public equity markets across different countries and it returns are comparable to other standard factors like size, value and momentum.

Behavioral Biases and the “Lottery Effect”

One of the possible explanations for underperformance of high beta stocks is the so called “lottery effect”

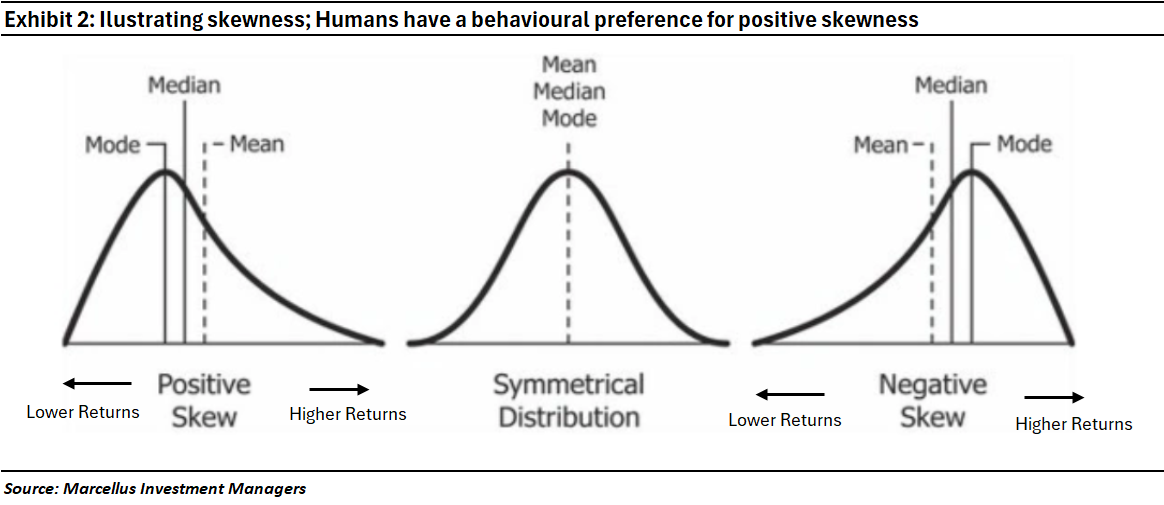

This is a human tendency to prefer activities or investments whose outcomes are uncertain or skewed—just like with gambling. The “Lottery effect” is basically a human behavioral preference for positive skewness or long shot investments which have a small chance of a large reward but a lower median reward (i.e. a gamble) – this payoff is shown in Exhibit 2.

This creates a hardwired preference for investments that resemble lottery tickets, even when the odds are poor. Investors pay too much for these stocks, chasing improbable wins while ignoring steady, lower-risk businesses with far more reliable outcomes. These stocks, which often include IPOs, distressed companies, or firms with high valuations and flashy narratives, are structurally overpriced and historically underperform over time.

Among other explanations for low-risk anomaly are leverage constraints— investors (think about most long only mutual funds) who wish to take on more risk but are unable to take on more leverage. Since they cannot borrow, they do the next best thing—they hold stocks with “built-in” leverage, like high-beta stocks. Investors bid up the price of high-beta stocks until the shares are overpriced and deliver low returns—similar to what we see in Exhibit 1.

The above explanations can perhaps partly explain rising valuations of small and mid-cap indices in India against the backdrop of rising retail investor ownership (who arguably are more prone to lottery effects) and an increasing share of mostly leverage constrained domestic mutual funds. Indeed, we also find higher proportion of small caps (>50%) among higher beta Q4 and Q5 quintiles shown in exhibit 1.

A Rules-Based Fundamental Approach to Low-Risk Investing

While low beta is a desirable characteristic of an investment, we do not think looking at beta is the best way to look at investment risk. For starters, measurement of beta itself is noisy (because it is based on stock volatilities and correlation between stock and benchmark returns). Correlations can change quickly and something that was low beta a month ago may suddenly become high beta today.

We believe for long-term investors, true risk is not merely short-term price volatility, but fundamental-based measures of safety (consistency of profitability, low leverage, and clean accounting). These along with other defensive characteristics are an important aspect of quality stocks overall. Along with these fundamental measures the risk of overpaying is equally important. Valuations matter no matter how low the beta. This could be particularly relevant during major risk-on events like war, pandemics, etc., when rotation into defensive strategies can increase valuations for low-beta stocks and hence lower their returns (relative to more cyclical, high-beta stocks) when the eventual recovery occurs (for example, 2009 or 2022).

In MeritorQ, we reject roughly ~80% of the investment universe basis fundamental measures of low risk like accounting risk, financial leverage and consistency profitability before selecting basis value and quality. Recently listed companies (within 1 year of listing) are not considered. Further, before each rebalance, the portfolio after selection step, is also vetted by Marcellus team for any unquantifiable corporate governance risks (promoters with doubtful integrity, shady history etc.) and any such identified company is completely removed from the portfolio. Hence, low risk investing is central to MeritorQ’s approach.

By following a disciplined, rules-based approach we aim to minimize our own biases and avoid investing in systematically overpriced stocks due to greed or fear, which often manifest in high-beta, high-volatility, narrative based “lottery” like stocks. Instead, we concentrate on companies with robust, stable long-term fundamentals and sensible valuations, where the odds of good performance are more favorable, and the risk of large declines is lower.

Taking a cricket analogy, while we might forgo opportunities to hit the ball out of the park (large outperformers) with this approach, we also avoid getting out in the process of chasing a big shot (large underperformers) and instead capture a disproportionate share of returns from stocks that modestly beat the market consistently. MeritorQ’s investment philosophy is therefore designed to enhance long-term compounded returns by mitigating the impact of large drawdowns, aligning with the core insight of the low-risk anomaly.

Regards,

Team Marcellus

If you want to read our other published material, please visit https://marcellus.in/