OVERVIEW

Published on: 22 March, 2019

Around the world, making money from stocks does involve a significant element of market timing. However, for a small minority of stocks in India, the classical value investing paradigm does not readily work. These companies are best understood using our ‘Consistent Compounders’ paradigm.

“Given the way price multiples have expanded for high-quality companies over the last decade, should investors be concerned about the sustainability of stock returns from such companies if they buy at current levels? Our answer is a resounding NO. As we show in Appendix 5 of this book, whether we look at bull market phases of the Indian stock market or bear market phases, all the evidence points in one direction – starting-period valuations have very little impact on long-medium run investment returns in India. The lack of correlation between starting-period valuations and long-term holding period returns seems to be specific to India.” – Rakshit Ranjan, Pranab Uniyal & Saurabh Mukherjea in ‘Coffee Can Investing: The Low Risk Road to Stupendous Wealth’, 2018, Penguin Random House

Value investing works

80 years ago Benjamin Graham and David Dodd introduced to the investing world the then revolutionary and interlinked concepts of ‘value investing’ and ‘margin of safety’ in their book ‘Security Analysis’. In an era ravaged by the Great Depression, the two men pointed out that the way to make money in the stockmarket with a high degree of certainty is to buy companies with low P/B, low P/E multiples and low debt. Such investments meant that your purchase price would be significantly below the fair value of the stock thus providing a ‘margin of safety’ for the investor.

In the years since the publication of Security Analysis, numerous academics have shown that value investing does generate superior results in the US market and elsewhere. Even more famously, Warren Buffett in a celebrated 1984 speech at Columbia University ( https://www8.gsb.columbia.edu/articles/columbia-business/superinvestors) reaffirmed the superiority of value investing to other investing approaches: “The common intellectual theme of the investors from Graham-and-Doddsville is this: they search for discrepancies between the value of a business and the price of small pieces of that business in the market. Essentially, they exploit those discrepancies without the efficient market theorist’s concern as to whether the stocks are bought on Monday or Thursday, or whether it is January or July, etc. Incidentally, when businessmen buy businesses, which is just what our Graham & Dodd investors are doing through the medium of marketable stocks…Our Graham & Dodd investors, needless to say, do not discuss beta, the capital asset pricing model, or covariance in returns among securities. These are not subjects of any interest to them….The investors simply focus on two variables: price and value.”

In India too one could argue that for the majority of stocks, value investing (i.e. buying companies when they are inexpensive on P/E) makes sense. In fact, one can divide the Indian stockmarket into broadly three sets of companies:

Type A stocks comprise around 80-90% of the Indian market. Such companies find it difficult to grow earnings over extended periods of time as they have no sustainable competitive advantages and hence no ability to generate a Return on Capital (ROC) in excess of the Cost of Capital (COC). The gap between ROC and COC is Free Cash Flow which in turn in the means by which a company finances its growth. Lacking sustainable FCF such companies struggle to invest in growing their businesses. Examples of such companies are India’s telcos and its airlines – companies with never ending volume growth but no sustainable competitive advantages and hence no earnings growth.

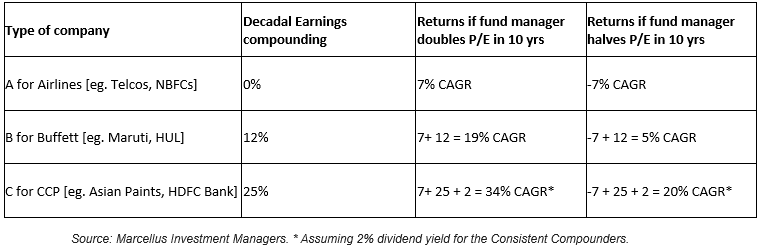

If you assume that you make returns from investing in any company from two sources – either the P/E expands or the earnings expand – with Type A stocks, your only hope of making money is that the P/E expands (since the earnings are unlikely to expand). If you find a fund manager who can double the Type A company’s P/E over a decade, your returns will compound at 7% CAGR. If the fund manager you have found has mistimed his investment i.e. he entered when the P/E was high (he wasn’t a value investor) and exited when the P/E had halved, your return will be -7% CAGR.

Type B stocks account for a further 5-10% of the Indian market and this segment includes good franchises like Maruti or HUL which have meaningful competitive advantages. As a result, in most years, these companies will have a ROC in excess of COC. The reinvestment of the free cash flow will allow these companies to grow the business at around 12% i.e. the same rate as nominal GDP growth on a cross-cycle basis.

Here too value investing works. If you can find a fund manager who enters Maruti at 13x P/E and exits a decade later at 26x P/E, the stock would give you returns of around 19% [12% from earnings growth and 7% from P/E doubling]. If, on the other hand, your fund manager has mistimed your investment i.e. he entered when the P/E was high (he wasn’t a value investor) and exited when the P/E had halved, your return will be 5% CAGR [12% minus 7%]. With Type B stocks, a committed value investor like Warren Buffett can generate high teens returns if he times his entry point well. In fact, this is exactly what Buffett’s legend is built around.

If you and I were living in America (or in any other large economy barring India), Type A & B stocks would form our entire investment universe. However, in the Indian stock-market there exists a third subset of stocks – Type C.

The Indian stockmarket has a unique subset of companies

As stated by our fund manager, Rakshit Ranjan, in our February 2019 newsletter (https://marcellus.in/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Marcellus_CCP_Newsletter_Feb_2019-1.pdf), “India is perhaps the only large economy where several industries are dominated by one or two players, and these dominant players make returns on capital employed (ROCE – earnings generated on each unit of capital employed on the balance sheet) significantly higher than the cost of capital (or COE – cost of equity) for several decades. For instance, it is not hard to find global players who dominate their industries – Walmart dominates US grocery retailing, Carrefour dominates French grocery retailing, Toyota dominates the mid-segment car market in Japan, Hanes dominates Europe’s innerwear market. However, none of these companies make ROEs substantially higher than their cost of equity… On the other hand, there are several industries in India where one or two companies not only have a dominant market share, their ROCEs have remained substantially above the cost of equity for decades in a row…”

We can call these Indian companies – whose ROCs are a million miles above their COC for decades on an end – Type C. The vast free cash flows that these firms generate decade after decade allow them to not only pay generous dividends (dividend yields for such firms tend to be 2-3%) but also reinvest in growing the business. Earnings growth for such firms tends to be around 25% per annum.

With a Type C firm, if our fund manager is able to get the timing of his entry and exit right, the results are spectacular: 25% earnings growth + 7% from doubling of P/E + 2% from dividend yield = 34% per annum return. However, since many of these firms are trading at optically high P/Es, let’s assume that their P/Es halve over the next decade. Even then these the Type C firms produce a return of 20% [25% earnings growth – 7% for P/E halving + 2% dividend yield]. Interestingly, even with P/Es halving over ten years, Type C firms produce returns similar to what Type B firms do with P/E doubling [20% vs 19%].

Investment implications

For 99% of Indian stocks, value investing provides the only route to decent returns (in the mid-high teens). The challenge that India’s Type C firms pose to Graham & Dodd’s value investment paradigm can be understood in the context of the investment framework that these legends had laid out in ‘Security Analysis’.

The value of a firm is nothing more than its future cashflows (discounted appropriately). These future cashflows are nothing more than the gap between ROC and COC. If the gap between ROC and COC does not close (say, because the Indian economy is not as competitive as the US economy or the Chinese economy) – as happens for the Type C companies in India – the value of the firm is very high. Such firms can therefore command very high P/E multiples. Our Consistent Compounders Portfolio consists of such companies (click here for more information: https://marcellus.in/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Marcellus_Consistent-Compounders_Mar-2019-1.pdf). To our regret, less than 1% of the stocks in the Indian market fall in this category! For the remainder of the investment universe in India – as in America – the rules of Graham & Doddsville can be successfully applied. The table below summarises the taxonomy of Types A, B & C that we have outlined above.

If you want to read our other published material, please click here

Saurabh Mukherjea is the author of “The Unusual Billionaires” and “Coffee Can Investing: the Low Risk Route to Stupendous Wealth”.

Note: the above material is neither investment research, nor investment advice. Marcellus Investment Managers is regulated by the Securities and Exchange Board of India as a provider of Portfolio Management Services and as an Investment Advisor.

Copyright © 2018 Marcellus Investment Managers Pvt Ltd, All rights reserved